‘Traitors’ No More?

By Syed Talat Hussain | News & Politics | Published 19 years ago

For an issue that only a few years ago evoked more international yawns than interest, Kashmir has consistently retained media limelight and global attention, competing with crises like Iraq and Afghanistan.

For an issue that only a few years ago evoked more international yawns than interest, Kashmir has consistently retained media limelight and global attention, competing with crises like Iraq and Afghanistan.

So it did not come as much of a surprise when Pugwash, an international organisation, chose Pakistan as a venue for a conference on Kashmir last month. Moots such as these have become a standard way to keep the gaze of diplomacy steady on global problems.

While it is difficult to fathom the actual contribution that the conference made in suggesting a framework to crack the problem of Kashmir, it was significant in, at least, one respect: Pakistani decision-makers crossed an important psychological barrier where Kashmiri leaders are concerned, whose close connections with Delhi traditionally earned them Islamabad’s ire and contempt. Omar Abdullah, head of the National Conference, and third-generation of the Abdullah family, commonly known in Pakistan’s ruling circles as the ‘ghaddars of Kashmir,’ made his maiden visit to this country, displaying the new flexibility that now dictates Islamabad’s fresh Kashmir outlook.

He, along with other participants of the conference, had a meeting with President Pervez Musharraf and were also feted by Foreign Minister Khurshid Mehmood Kasuri — a dinner made famous by the verbal bout between Pakistan’s Kashmir experts and the pro-India Kashmiri leaders.

The official welcome accorded to the wide array of Kashmiri leaders, whose antecedents and political standing were once deemed questionable by the Pakistani establishment, is in line with the guarded reciprocity that the Indian and Pakistani government are supposed to show in the carefully-paced Kashmir peace process.

One of the million shrapnels that killed peace initiatives on Kashmir has been the lack of trust in the Kashmiri leaders who are sympathetic to the two sides in the bloody story: India and Pakistan. Delhi and Islamabad both denigrated Kashmiri leaders who represented Kashmiri versions of the official positions, excluding them from any constructive consideration: Delhi traditionally kept the All Parties Hurriyat Conference and the militant outfits at bayonet’s length, and Pakistan eschewed any contact with those who did not call for the right of self-determination of the Kashmiri or rallied around the emotive slogan of joining Pakistan.

Not anymore. Delhi, in its own incremental, schematically circuitous way has warmed up to the idea of making contact with the Kashmiri leaders who oppose the idea of Kashmir being part of India. Pakistan has responded in kind and has an open-door policy, allowing the entry of all sorts of claimants to Kashmiri interests in the fold of its diplomacy.

Yet too much cannot be read into these contacts. Officials who make arrangements for hitherto unknown or unwelcome Kashmiri leaders during the day, sit in the evenings and vent caution against the dangers of their own policy.

The most obvious danger that they mention is that soon there might be so many mouths speaking on behalf of the Kashmiris that the real issue and its proponents will be squeezed for space, if not completely sidelined. Ostensibly, different Kashmiri points of view are being brought at par with each other, in search of an “out of the box” solution.

The most obvious danger that they mention is that soon there might be so many mouths speaking on behalf of the Kashmiris that the real issue and its proponents will be squeezed for space, if not completely sidelined. Ostensibly, different Kashmiri points of view are being brought at par with each other, in search of an “out of the box” solution.

Some official quarters see a lot of merit in this attempt. “As long as these leaders from different parts of Kashmir can generally agree on changing the status quo in Kashmir, we do not have a problem in entertaining them,” says a member of President Musharraf’s small, informal group of advisors on India.

The assumption is that at least theoretically a common ground is now visible on which the diverse range of interests can connect. From Pakistan’s point of view this means greater currency among Kashmiri leaders of President Musharraf’s idea of de-militarisation, self-rule for Kashmiris, and joint control of the Kashmir territory by a body on which representatives of Kashmiris, India and Pakistan sit.

Practically, while the idea has done many rounds, it has not caught on in Delhi. Even Omar Abdullah, who has his own plan of maximum autonomy for the two territories that makes the LOC irrelevant, has not shown any enthusiasm for the scheme.

“Its details have not been provided to us, and from what I have heard it seems like a pretty difficult scheme to implement,” he remarked during an interview.

The other danger of adding more seats on the table of Kashmiri leaders, is that it would be hard to withdraw the invitation later without creating an awkward diplomatic situation.

Delhi’s engagement with pro-Pakistani or pro-independence leaders from Kashmir is heavily qualified. It is preconditioned by its insistence that they must shun violence, and be willing to participate in an electoral exercise, as well as be more patient with its routine insistence that Kashmir is an integral part of India and that the Indian borders would not change in search for a solution. While India has been selective in applying these preconditions, it has been very steady in articulating them officially.

Pakistan has been more generous in opening its doors; Islamabad has not laid down any such condition which, if unfulfilled, could make it revise its new Jammu and Kashmir guest list.

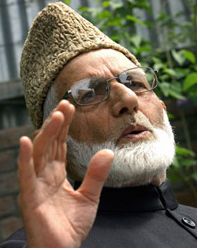

Part of the reason is that Islamabad has hastily bowdlerised its Kashmir policy script. References to the UN Security Council resolutions are a rarity or mere pro forma utterances. On more than one occasion, President Musharraf has spoken of the impracticality of the plebiscite, as well as the option of Kashmir becoming part of Pakistan. Official defense of the Kashmiris’ right to pick up the gun and fight the occupation forces too, has been diluted to the point of non-existence for fear of Pakistan coming across as an advocate of terrorism. Leaders like Syed Ali Geelani are considered “dividers” and “an impediment to peace.” Under these circumstances the opening of the debate on the Kashmir solution to different voices, while being very democratic and in tune with the changed circumstances, also poses the danger of the issue being defined in terms that are unjust and detrimental to Kashmiri interests. That is a danger that very few in Islamabad are talking about these days.

The writer is former executive editor of The News and a senior journalist with Geo TV hosting a prime time current affairs program.