The Art of Subversion

By Sama F | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 11 years ago

To give a little context to his latest body of work at the Canvas Gallery, visual artist Muzzumil Ruheel begins with a joke: Someone from the Middle East arrives in Pakistan and asks a group of women where the washroom is. The women obviously don’t understand a word of his Arabic, but they quickly pull their dupattas over their heads.

Lahore-born Ruheel, who has been living in Karachi for the past three years, attempts to subvert this kind of reverence for anything Arabic with his exhibition titled …but some of them never happened? Ruheel feels that we’ve placed the Arabic language (and perhaps, by extension, the Arab world) on such a high pedestal that, if someone were to curse us in Arabic, we’d probably interpret it as divine injunction.

To make his point, Ruheel uses two different and somewhat contradictory mediums in his artworks: extremely detailed and intricate calligraphy juxtaposed against old, black and white and sepia-toned photographs. Some may find the integration of calligraphy, traditionally promoted as the religiously ‘permissible’ art form in Muslim orthodoxies, with photography — particularly of the human form — as being problematic, or see the mixing of the sacred and profane as an unnecessary provocation.

But this is exactly what Ruheel wants you to think, at first. The calligraphy, in striking tulut script — one of the most commonly used styles for religious scripture, renowned for its beauty and decorative purposes — may seem like Quranic verses, but Ruheel reveals that “they’re just ordinary stories,” not scripture. He wants viewers to question their taken-for-granted assumptions about language, calligraphy, notions of sacredness, and to look closer and actively read the text as opposed to passively observing it. As Muslims, our minds automatically draw the connection between calligraphy and God’s word; it’s something we, including the artist, have grown up with and is ingrained in our consciousness.

But this is exactly what Ruheel wants you to think, at first. The calligraphy, in striking tulut script — one of the most commonly used styles for religious scripture, renowned for its beauty and decorative purposes — may seem like Quranic verses, but Ruheel reveals that “they’re just ordinary stories,” not scripture. He wants viewers to question their taken-for-granted assumptions about language, calligraphy, notions of sacredness, and to look closer and actively read the text as opposed to passively observing it. As Muslims, our minds automatically draw the connection between calligraphy and God’s word; it’s something we, including the artist, have grown up with and is ingrained in our consciousness.

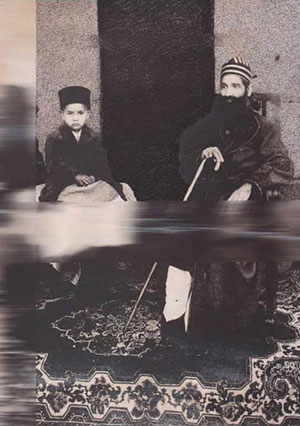

One work that illustrates this is ‘Will I Be Next?’ in which a young boy is seated beside a bearded, distinguished-looking older man in a long robe, prayer cap and a walking stick. Ruheel’s signature calligraphy serves as a backdrop. It’s not clear who the people are, but judging from the title, they could be his own family members. He may be trying to show how beliefs are unquestioningly inherited and passed down from one generation to the next. By never questioning our elders, we simply adopt their ways.

In ‘Inherited Legacies,’ the face of a nawab, dressed in fine clothing and jewels, is veiled by a geometric shape containing more calligraphy. Perhaps Ruheel is suggesting that some people benefit and grow wealthy from our unquestioning obediance, as well as our ignorance of the text.

This review was originally published in Newsline’s March 2014 issue.

The writer is a journalist and former assistant editor at Newsline.