Musharraf’s Battle for Survival

By Zahid Hussain | News & Politics | Published 18 years ago

General Musharraf has galvanized the opposition with his sacking of Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry. The furore over the dismissal of the country’s top judge for alleged misconduct has exposed the fissure that had widened in the preceding years, fuelling outrage against General Musharraf and the military. Lawyers are now joined by rights campaigners and political activists, in a show of solidarity with the ousted chief justice, who has become a symbol of the pro-democracy movement in the country. The protests have become much more frequent and widespread, plunging the country into its most serious political crisis since the military seized power in a bloodless coup in October 1999.

For the first time in Pakistan’s history, the judiciary is up in arms against the government. Several judges have resigned in protest over the president’s unilateral dismissal of the chief justice, which they term “illegal’ and ” unconstitutional.” “The general has started the war within for only one reason: to perpetuate his rule,” says Dr Tariq Hassan,” a senior attorney. “By doing so he has not only denigrated the highest judicial institution in the country, but has also caused grievous harm to his own constituency — the army.”

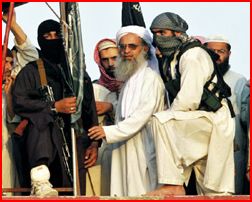

With opposition anger still raging over his dismissal of the chief justice, the crisis is exacerbated by the growing stridency among Islamic radicals who strive to enforce their own brand of a rigid, conservative Islamic order on the country, taking vigilante justice to the streets of the capital. Wielding sticks, bearded students of a local seminary have been roaming around Islamabad raiding video shops. Zealots have also become an increasingly common sight at the capital’s traffic lights, where they warn women to stop driving, as it is a “sin” against Islam. Hundreds of students of Madrassah Hafsa, shrouded from head to toe in black burqas, have raided houses they claim are being used as brothels in residential neighbourhoods in Islamabad.

These are all signs of a creeping campaign to Talibanise Pakistan that is spreading to the capital and some other towns from remote tribal areas along the Afghan border. Like-minded religious vigilantes in the North West Frontier Province have asked parents to pull out their daughters from schools, and have forcibly stopped female schoolteachers and health visitors from work.

Such vigilantism is backed by Muslim clerics who have set up a parallel Islamic judicial system to try those they believe to be involved in “immoral acts.” They have set up a court within the precincts of Lal Masjid, right in the heart of the nation’s capital, indicating a complete paralysis of the state. Their actions are reminiscent of the rise of the Taliban, whose law-and-order campaign was a path to gaining power in Afghanistan.

Such vigilantism is backed by Muslim clerics who have set up a parallel Islamic judicial system to try those they believe to be involved in “immoral acts.” They have set up a court within the precincts of Lal Masjid, right in the heart of the nation’s capital, indicating a complete paralysis of the state. Their actions are reminiscent of the rise of the Taliban, whose law-and-order campaign was a path to gaining power in Afghanistan.

As part of their campaign, Lal Masjid clerics last month issued a fatwa, calling for the sacking and trial of Tourism Minister Nilofer Bakhtiar, who was photographed hugging her instructor after completing a parachute jump in France. The clerics deemed it “un-Islamic behaviour.” “Now I fear for my life,” Ms Bakhtiar told a Senate Standing Committee.

While many Pakistani political analysts agree that the growing influence of radical Islam presents an increasingly serious threat to Pakistan’s internal political stability and to regional security, Musharraf’s government has done little to stop it. Critics accuse the military of allowing the radical mullahs to act with impunity to protect the continuation of the general’s rule by pandering to the fundamentalists. Few believe that the government is helpless or incapacitated against the religious extremists. In fact, the government’s shameful capitulation has encouraged zealots in other parts of the country to emulate the trend set by radical clerics of Lal Masjid and the burqa brigade of Madrassah Hafsa. The government defends its policy of inaction by saying it wants to avoid furthur opposition from conservative Muslims and violent reprisals from militants.

While the government pursues a policy of appeasement, the militants have stepped up their terrorist activities, targeting top government officials and the army more frequently than before. The latest suicide bombing aimed at federal Interior Minister Aftab Sherpao during a rally in Charsadda that killed more than two dozen people is a chilling reminder of Pakistan itself having turned into a theatre of war spilling over from Afghanistan. The multi-dimensional crises threatens to fragment the nation along political, religious and ethnic lines. This also raises serious questions about President Musharraf’s own survival in power.

General Musharraf has announced his intention of seeking election for another term, but there is no indication of his doffing the uniform. This makes the situation more serious, raising fears of further political instability. Defence analysts maintain that the army will be watching the situation with concern as public outrage turns against their own institution.

In an attempt to find an expedient way to dampen the protests, broaden his increasingly narrow political base and reassure his re-election for another five years, Musharraf is desperately seeking new allies among the mainstream political parties. He has apparently decided to strike a deal with bitter political rival Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party. Some of Musharraf’s close aides believe the compromise could provide the best hope for him.

In an attempt to find an expedient way to dampen the protests, broaden his increasingly narrow political base and reassure his re-election for another five years, Musharraf is desperately seeking new allies among the mainstream political parties. He has apparently decided to strike a deal with bitter political rival Benazir Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party. Some of Musharraf’s close aides believe the compromise could provide the best hope for him.

But can the emerging partnership with Bhutto save him?

Bhutto’s recent statements saying she was willing to work with Musharraf in the “national interest” lend further credence to the reports about an impending rapprochement. Over the past few months, Musharraf has telephoned Bhutto at least three times, and the president’s most senior aide, Tariq Aziz, has been holding negotiations with her in Dubai. In a show of good faith, the government is already starting to take confidence-building measures. Last month they closed down the NAB cell investigating corruption charges against Bhutto, her husband, Asif Ali Zardari, and some other politicians. The transfer of vice chairman NAB, Wasim Afzal, is also the result of the ongoing negotiations between the two sides. Bhutto’s refusal to join a grand opposition alliance, which was to have included the MMA, and the PPP’s support for the government’s Women Protection Bill were believed to be the part of the CBMS. Musharraf called to thank Bhutto after the passage of the Bill, which many of his own allies in the PML (Q) had grudgingly voted for.

For Musharraf, a compromise with one of the most powerful mainstream political parties has become critical, as he faces growing public discontent and street protests on his ill-conceived suspension of the chief justice on incredibly flimsy charges. Most legal experts agree that the President would find it extremely difficult to extricate himself from the self-created predicament and ride out the current political storm. A deal with the PPP would not only help him divide the opposition, but also ensure his election for another five-year term.

On the other hand, the deal would allow Benazir Bhutto to return to Pakistan to campaign for her party in the parliamentary elections due to be held by the end of this year. The corruption charges against Bhutto and her husband, Zardari, will either be dropped or simply not pursued. The agreement may lead to relatively free and fair elections, paving the way for the PPP to emerge as a major contender for power in the centre, as well as in Sindh and the Punjab. But there is also a downside to the PPP’s rapprochement with Musharraf. Many political observers believe that the party may loose its credibility by joining a military-led dispensation.

On the other hand, the deal would allow Benazir Bhutto to return to Pakistan to campaign for her party in the parliamentary elections due to be held by the end of this year. The corruption charges against Bhutto and her husband, Zardari, will either be dropped or simply not pursued. The agreement may lead to relatively free and fair elections, paving the way for the PPP to emerge as a major contender for power in the centre, as well as in Sindh and the Punjab. But there is also a downside to the PPP’s rapprochement with Musharraf. Many political observers believe that the party may loose its credibility by joining a military-led dispensation.

Musharraf and Bhutto, until now, appeared to be the most unlikely political partners. The general had often accused Bhutto of having plundered the country during her two terms as prime minister in the 1990s and vowed not let her return. Bhutto, on the other hand, derided him for being a usurper who had allowed Islamic extremists huge political space. But the politics of expediency may now bring the two adversaries together.

A major point of contention is whether Musharraf would continue to hold the dual posts of president and chief of army staff. According to some sources, Musharraf may agree to take off the uniform after the elections. Such a deal may be mutually beneficial to both Musharraf and Bhutto, but it may not necessarily lead to the restoration of full democracy in the country. There is no indication that the military’s role in the country’s politics would in any way be curtailed. The only way out of the crisis is for Musharraf to hold free and fair elections and leave it to the electorate to decide the future course of the country.

The writer is a senior journalist and author. He has been associated to the Newsline as senior editor at.