Miniature’s Postmodern Face

By Salwat Ali | Art | Arts & Culture | Published 18 years ago

When the classical Mughal miniature became modern it was considered a quantum leap forward. Barely waiting for audiences to assimilate this newness, the genre began pushing the boundaries of contemporary art. Today, radically removed from its parent model, the (non) miniature has moved into a postmodernist phase. A display of 10 artworks by Muhammad Zeeshan, at Chawkandi Art, conforms to this new mindset. Riddled with innuendoes, the mixed media art needs to be located in its correct perspective, if it is to be understood at all.

Postmodern art is a term used to describe art which is thought to be in contradiction to some aspect of modernism, or to have emerged or developed in its aftermath. One compact definition is that postmodernism rejects modernism’s grand narratives of artistic direction, eradicating the boundaries between high and low forms of art, and disrupting the genre’s conventions with collision, collage, and fragmentation. Postmodern art holds that all stances are unstable and insincere, and therefore irony, parody, and humour are the only positions that cannot be overturned by critique or revision.

Postmodern art is a term used to describe art which is thought to be in contradiction to some aspect of modernism, or to have emerged or developed in its aftermath. One compact definition is that postmodernism rejects modernism’s grand narratives of artistic direction, eradicating the boundaries between high and low forms of art, and disrupting the genre’s conventions with collision, collage, and fragmentation. Postmodern art holds that all stances are unstable and insincere, and therefore irony, parody, and humour are the only positions that cannot be overturned by critique or revision.

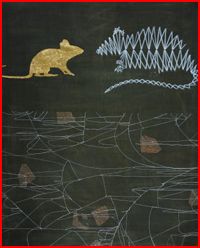

In the Chawkandi exhibition, paradox underscores Zeeshan’s work as he explores contradictions inherent between the spoken word and subsequent human conduct. However, his means of projecting hypocrisy and insincerity is complex and far-fetched as he resorts to a bizarre and bewildering array of forms and images. Extensive use of a rodent as protagonist, floral forms and non-miniature materials, such as thread, stitchcraft and 3D effects created by punched holes, impress the mind, at first glance, as a very personalised coded language. But the artist points out: “Rats for me represent a way of life rather than the rodent itself.” Equating the rodent’s habits with human traits, he builds a case of calculated deception and decimation. Explaining his paintings of rats devouring what appears to be a very sensitive female organ, he opines, “Rats are very careful about what they eat. So before they attack a certain food they have to be sure that it is good for them and only them in all ways. Once that is determined they start eating that food from within. They hollow the form and let the walls stay intact so that if one looks at the food one is not able to judge that it has been eaten, the walls are so well intact. These rats have carried plague with them and have been known to have wiped out civilisations within a week’s time. One wonders if our political leaders are not doing the same. Causing our minds to rot, leaving our society, culture and infrastructure weak and hollow from within by only benefiting themselves.”

A trained miniature artist, Zeeshan demonstrates exquisite workmanship. He retains the miniature mannerism not just in drawing and painting but extends the same delicate intricacy to the non-miniature craft of weaving, threading, stitching and punching. This emphasis on technique highlights the importance of methods and procedures of artmaking rather than the containment of an idea. Modernism seeks closure in form and is concerned with conclusions, while postmodernism is open, unbounded, and concerned with process and “becoming.”

A trained miniature artist, Zeeshan demonstrates exquisite workmanship. He retains the miniature mannerism not just in drawing and painting but extends the same delicate intricacy to the non-miniature craft of weaving, threading, stitching and punching. This emphasis on technique highlights the importance of methods and procedures of artmaking rather than the containment of an idea. Modernism seeks closure in form and is concerned with conclusions, while postmodernism is open, unbounded, and concerned with process and “becoming.”

The uncanny nature of this body of work also gains validity when examined in the context of theoretical art. Conceptual art is sometimes labeled as postmodern because it is expressly involved in the deconstruction of what makes a work of art, “art.” It is often designed to confront, offend, or attack notions held by many of the people who view it and is, therefore, regarded with particular controversy. The artist’s not so ambiguous recourse to female genitalia is bound to generate mixed reactions amongst audiences as the imagery often borders on the gross and the unpleasant.

Self-aware and consciously involved in a process of thinking about himself and society, Muhammad Zeeshan is “demasking” pretensions in a deconstructive manner in his current series of paintings. “I think we have forgotten to question ourselves and our actions,” he asserts. “As a nation we have become zombies. I am just trying to stimulate a questionnaire. When I was a child I was scolded for asking ‘why’ because it marks the territory of doubt, hence one must refrain from asking it. I feel that we are so accustomed to not asking the question ‘why’ that we have stopped thinking and analysing everything and anything that goes on around us and within us.”