Women of Substance

By Tehmina Ahmed | Arts & Culture | Movies | Published 22 years ago

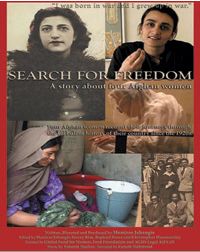

Search for Freedom, a documentary directed by Manizae Jahangir, is about four Afghan women and their struggle to bring some semblance of sanity to lives disrupted by war.

The women run the gamut of social class, ranging from the aristocratic Princess Shafiqa Saroj,King Amanullah’s sister, to the simple village woman, Mohsina, whose husband was slain by the mujahideen.

The women run the gamut of social class, ranging from the aristocratic Princess Shafiqa Saroj,King Amanullah’s sister, to the simple village woman, Mohsina, whose husband was slain by the mujahideen.

Displaced by the rapid changes overtaking their beloved homeland, the women focus in on what these changes have meant to them. Shafiqa Saroj was a reformer in her time, with her brother, the liberal King Amanullah, supporting women’s desire to step out of purdah and play a role in public life. In the film we see her going through family albums, recounting the story of her royal line. Even as she regrets the ravages of the mujahideen and the Taliban who followed them, the princess retains her composure and sense of proportion.

Mohsina’s story is a brutal one, for she belongs to the Shia Hazara tribe singled out by the Taliban for retribution. Her village in Bamiyan province was razed to the ground, all the men shot in cold blood, leaving the women to handle their burial. She now lives in a refugee camp in Peshawar, along with her children. They have enough to eat, she says, but the joy has gone out of their lives.

There is Mairman Khadija Parveen, a rebel of sorts, the first female singer to be featured on Kabul radio. At 14, she was married to a man of 85, but separated from him after a year and a half of marriage. She has 700 songs to her credit, but the move from Afghanistan has severed her from her source of inspiration.

Then there is Sohaila, a teacher and aspiring medical student who works in a RAWA-run hospital. Sohaila has lived through the dark days of the Taliban regime and describes how singing and even laughing in public were banned for women. Teaching girls was a taboo and her classes had to be held surreptitiously, the girls coming in at different times, hiding their books inside their burqas. She became suspect, and was given a warning from the Taliban. Sohaila eventually opted to move to Peshawar.

She is the most articulate and the most analytical of the four women. Sohaila eloquently describes the pain of living in exile, saying, “our spirits are gone and our senses dulled.” Sohaila is glad to see the last of the Taliban, but does not belong to the school of thought that claims that all is well in Afghanistan after their demise. She identifies poverty as the key issue, saying that women’s problems will not disappear by abandoning the veil.

The common thread that runs through the women’s lives is not just the displacement and savagery of war, but the strength and resilience with which the women have faced their problems and made an adjustment to the situation that has been thrust upon them.

The film has a professional touch in terms of camera work, direction and editing. For a first film it is a remarkable piece of work. Manizae, whose mother is the pioneering Asma Jahangir, is clearly not just a chip off the old block, but a film maker to watch out for.