The Truth Hurts

By Talib Qizilbash | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 18 years ago

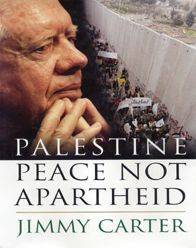

One word has branded Jimmy Carter an anti-Semite.

The 2002 Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian, author, activist and former US president has been soundly attacked in the press for describing the structure and manner of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands as apartheid. Critics of varied professional, political and racial backgrounds have accused Carter’s latest book, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, as being, among other things, “moronic,” “laughable,” “slapdash” and “riddled with errors and bias.” Such work, claim many of these critics, which compares Israeli treatment of Palestinians to that of blacks in white-dominated South Africa, can only come from someone who has something against Jews.

The 2002 Nobel Peace Prize-winning humanitarian, author, activist and former US president has been soundly attacked in the press for describing the structure and manner of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian lands as apartheid. Critics of varied professional, political and racial backgrounds have accused Carter’s latest book, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, as being, among other things, “moronic,” “laughable,” “slapdash” and “riddled with errors and bias.” Such work, claim many of these critics, which compares Israeli treatment of Palestinians to that of blacks in white-dominated South Africa, can only come from someone who has something against Jews.

America’s Anti-Defamation League (ADL) released the largest co-ordinated attack against the book. Full-page ads from the Jewish lobby group ran in leading US newspapers trivialising Carter’s four decades of involvement in the Middle East peace process by claiming that nothing (yes, nothing) in his book was true. The ADL’s ads lead off with the following lines: “There’s only one honest thing about President Carter’s new book. The criticism.” Moreover, the organisation’s director argued that the book should be judged by its cover (read: the controversial title), and thus wholly ignored.

The use of the word apartheid to characterise the Israeli occupation of Palestinian land is undoubtedly controversial, but it is also brave. And while objections to its use could be raised ad nauseam — Israel’s domination of Palestinians stems from a military occupation, and not racial hatred, etc. — the fact is critics who outrightly dismiss the ugly term as wholly inaccurate are either in denial, or, perhaps, trying to continue the long-running campaign of hiding the truth of the Middle East crisis from the under-read American public.

Apartheid is defined as “an official policy of racial segregation practiced in the Republic of South Africa, involving political, legal and economic discrimination against non-whites.” Or alternatively, “as any policy or practice of separating or segregating groups.”

Clearly, there is a policy of segregation in the occupied territories — a multitude of checkpoints and the over 700km-long West Bank security barrier speak to that. So the second definition undoubtedly applies. Determining whether Israel’s domination over Palestinians meets the criteria of the first definition requires two things: first, replacing the words ‘South Africa’ and ‘non-whites’ with the words ‘Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories’ and ‘Palestinians,’ respectively; second, analysing the three key elements that make up the nature of apartheid: the status of the policy, race, and political, legal and economic discrimination.

Israel’s policies are indeed based on racial segregation. Israel has structured its country, Gaza and the West Bank in such a way that Jews, the minority, have minimal contact with Palestinians and have access to the majority of the resources. The underlying cause may not be simple feelings of racial superiority, but it is not chiefly about security either — yes, security for Israelis is a legitimate concern, but the argument and need for security is abused by provoking Palestinian hostilities (bulldozing the homes of innocents, for example). Carter shows that the basis for Israel’s forceful land-grabbing is clearly based on notions of a God-given birthright of a Jewish homeland and the resulting need to rebuild the Kingdom of David. Still, the motives of racial segregation are irrelevant. The fact is that it is happening, and just like in South Africa, Israel’s official policies involve political, legal and economic discrimination against a distinct racial group. Palestinians, both Muslims and Christians, have little access to Israeli courts, are cut off from each other, face daily harassment at dozens of checkpoints, have their produce held up at borders and left to rot, and are denied from selling their goods in Israeli markets. Their economy has been destroyed to such an extent that the Palestinian government is virtually broke. There are not enough funds to pay salaries to the police, teachers and nurses.

Esteemed South African professor of international law John Dugard, who has served on the International Court of Justice, wrote an op-ed in a US newspaper last year: “Many aspects of Israel’s occupation surpass those of the apartheid regime. Israel’s large-scale destruction of Palestinian homes, levelling of agricultural lands, military incursions and targeted assassinations of Palestinians far exceed any similar practices in apartheid South Africa. No wall was ever built to separate blacks and whites.”

So the word apartheid seems more than appropriate.

This doesn’t mean Carter’s book is free of flaws. He optimistically concludes that his 1979 Camp David Accords, if fully adopted and adhered to by Israel, could have brought lasting peace to the Middle East crisis. Of course, as critics point out, he has made no reference to other developments in the region: the Iranian Islamic revolution, the rise of the Taliban, or Saddam Hussein’s stranglehold on power in Iraq, none of which have had benign results. The phenomenon that is Al-Qaeda is totally left out of the Middle East equation too. He also fails to place a very critical eye on Arafat. While he may point out leadership shortcomings, he does not tackle the widespread allegations that Arafat supported terrorism. One of the most contentious issues he raises is the claim that the Six-Day War was initiated by Israel, despite his own assessment that Egypt’s blockade of the Straits of Tiran and “menacing moves” by Arab forces preceded Israel’s pre-emptive strikes on Syria, Egypt, Iraq and Jordan.

Again, though, that doesn’t make Carter’s work an inaccurate analysis of the troublesome situation. Carter’s refusal to debate one of his harshest critics, famous defence attorney and Harvard professor, Alan Dershowitz, has, though, undermined his power in the court of public opinion. “There is no need for me to debate somebody who, in my opinion, knows nothing about the situation in Palestine,” said Carter.

In an editorial in the Boston Globe, Dershowitz rightly retorted: “Carter’s refusal to debate wouldn’t be so strange if it weren’t for the fact that he claims he wrote the book precisely so as to start a debate over the issue of the Israel-Palestine peace process. If that were really true, Carter would be thrilled to have the opportunity to debate.”

His book has been promoting the debate in other ways, though. The tank-full of criticism that has attempted to level the sales of his book has itself generated heated, and sometimes thoughtful, debate. Editorials and articles against him have spawned published reactions by Carter and have ensured that his speaking engagements at universities and other public forums have been sold out. The book, though, is not the end of Carter’s message. A documentary, entitled He comes in Peace, is being made by The Silence of the Lambs director Jonathan Demme.

Simply, Palestine Peace is far from being an anti-Semitic rant. Carter does not demonise Jews as his critics are doing to him. He blames leaders on both sides for the failure to achieve peace. It’s the politicians who want war, not the people, suggests Carter. He reveals that in a 2006 poll, “62% of Israelis favoured direct talks with Hamas.”

Carter has cited many problems and failures of the Palestinians and the Arab world too. Moreover, his book clearly indicates he was once complimentary of Israel. After his first visit to Israel as Governor of Georgia in 1973, Carter “left convinced that the Israelis were dominant but just, the Arabs quiescent because their rights were being protected, and the political and military situation destined to remain stable until the land was swapped for peace.”

Throughout his book he repeats what he believes to be the foundations for peace. They are far from being one-sided: Israel’s right to exist in peace, and the Arab world’s open acknowledgement and guarantee of it; the definitive resolution of the internal debate in Israel in order to define Israel’s “permanent legal boundary,” which should coincide with international dictates established by the UN (and approved by Israel’s biggest supporter, the US), specifically, “those borders prevailing from 1949 to 1967″; and the assurance that “the sovereignty of all Middle East nations and the sanctity of international borders must be honoured.”

In other words, Carter pleads for change and compromise on both sides.

On the 40th anniversary of the 1967 Six-Day War next month, taking a comprehensive, critical, yet honest look at the history and status of the polarising and never-ending Middle East crisis is more than merely interesting or fitting: factor in the constant decline in living conditions for Palestinians, the rise of global terrorism and wider unrest in the Arab and Muslim world, and it becomes highly essential.

Sadly, Carter’s analysis that includes highlighting Israel’s human rights abuses, broken promises relating to their own negotiated agreements and economic strangulation of Palestinians continues to be unfairly interpreted as anti-Semitism. Do his critics really believe so?

Or are they simply upset that someone of Carter’s stature — someone who has remained intimate with the situation for four decades — has decided to tell Americans in plain English what the rest of the world already knows?