Roohi Bano: The Soul Survivor

By Salman Asif | Arts & Culture | People | Profile | Published 10 years ago

“One must still have chaos in oneself to be able to give birth to a dancing star.” – Friedrich Nietzsche

Houses often become resumes of their inhabitants. This house, snuggled in one of Lahore’s leafiest, snootiest suburbs, is certainly an embodiment of its dweller. It is also an edifice that stubbornly belies its pretentious locale.

An eerie, gnawing silence hangs heavy over this property, chewed in and vomited out by years of neglect. As its green metal gate hesitantly squeaks ajar, time and space liquesce into a desolate spectacle that must only be fantasised – materialised by some astute horror movie set designer.

And then there is the resident phantom of this opera. A spectre that stands resolutely tall — above a putrid profusion of disintegrating, charred furniture pieces, the scattering of old, moth-consumed magazines, eroding walls ablaze with one-liner scribbles, and multiple invasions of cobwebs colonising each corner with a flourish.

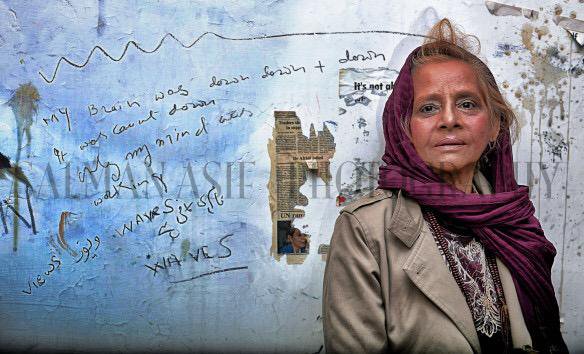

Regally watching over this decomposing morass like a victor among the vanquished is the lady of the estate. She ushers me into this realm with a manifestly rehearsed, royal ‘yes’ nod and a fleeting flash of a smile that quivers stealthily for a microsecond before it vanished. Hers is a face aglow with deep pink coatings of freshly layered make-up caked upon the sagging skin, chipped red nail varnish, unruly dry strands of golden dyed hair and at least four layers of clothing on a sultry April afternoon. This is Roohi Bano.

This is, indeed, none other than the once, not too long ago, undisputed doyenne of art house style Pakistani TV drama. The actor par excellence, the protagonist whose iconic screen persona of a bumbling, stammering, absent-minded urban girl (Kiran Kahani) was to later morph into a chilling illustration of life imitating art.

With a Masters degree in Psychology, Roohi Bano in her present state is a case study unto herself that unfolds before one’s startled eyes like a magical realist narrative. Who knows when Roohi Bano — the winner of three prestigious Graduate Awards, the Nigar Award, the President’s Pride of Performance Award and two PTV awards — was first diagnosed with an emotional disorder. Was it when her life spun and spiralled off on a doomed trajectory of being exploited, siphoned off by multiple parasitical relationships? Or perhaps when she lost her mother in a mysterious fire accident? Or was it when her only son Ali was found drenched in his own youthful blood, savagely murdered in 2005? Who knows!

For years, Roohi Bano has remained obscure, shrouded by the dust of time. Recently, there has been another unveiling of this TV royalty. The avant-garde screen celebrity is ubiquitous, once again, on TV in a new-fangled avatar. Rather poignantly, Roohi Bano, in her current state of being, is no less sought after for assorted sprightly TV morning shows with their inexhaustible appetite for footage. Morning shows vie factiously to have her on their sets, routinely coaxing her to appear as a ‘special guest.’ In truth, packaged as a celebrity ‘freak,’ her dishevelled TV appearance is hailed as a ratings booster by nauseously chirpy, artificially affectionate and scheming, manipulative morning shows.

Nothing degrades Roohi Bano, not even the sadistic fetish for recalling her from a dignified oblivion — of course, forever, in the name of ‘paying long overdue homage’ to an unforgettable, yet forgotten TV figure — to the blinding glare of digital spotlights and boorishly intrusive cameras. There she is paraded and patronised, laughed at and ridiculed — ultimately tut-tutted at. Most galling, however, is her being skillfully talked into becoming distraught, reduced to tears on live camera, while the anchorperson herself in faux distress-mode widens her misty eyes, sighs deeply, benevolently flutters the extra-long fibre eyelashes, shakes her head in Barbie-like disbelief and then, almost choking, declares Roohi Bano’s presence to be too heart-wrenchingly moving for the show to continue without a commercial break, as the TV screen explodes into riots of colour, movement and noise — instant, life-affirming relief.

Alas! Anyhow, back to my encounter with Roohi Bano. She has invited me over to her abode to do a photo shoot and to listen to the silent requiem of Nay (Persian) — the flute that tells the travails of its separation from the reed. In a trance-like moment, Roohi Bano alludes to the opening lines of Rumi’s Mathnavi, the epic poem encompassing over 250,00 couplets.

As we talk, her unique literary genius sparkles like dispersed jewels from beneath the confusion of melancholic rubble. Yet, this may not be quite so extraordinary. From Byron to Dylan Thomas, Vivien Leigh to Monroe, Tolstoy to Hemingway and beyond, an entire constellation of the art world’s most luminous stars may have had a touch of mental ‘illness’ to thank for their behaviour. Psychologists agree as much, and Roohi Bano fits, nay, lives the template.

“I love to act. Acting is all I have left now, haven’t I? Actually, at times I feel that I am one of my own imposters. It seems that I am impersonating a stranger, someone — I no longer am.” Her words are reeled out with pregnant, immaculately honed stage-play pauses.

And then there is the sparkling laughter: “Salman, you better be good at your job when you do my write-up and the photo shoot, because you will be defining the indefinable,” she chuckles, pointing at a statement scribbled with a piece of coal on the wall of her reception room: “My brain was down, down and down — it was count down; only my mind was working. Views are waves.”

Roohi Bano’s sharp cognisance of the world around her is astounding. From international relations to the current TV soaps, literary trends and climate change issues — she’s not just connected, but engaged in the discourse. She’s far, far from a person whose vision of herself and her place in the world is blurred by any means. And yet, there is the staggering incoherence.

At one point while looking around with ersatz panic, as if evading imaginary, invisible eavesdroppers spying on the classified nature of our conversation, she whisperingly advises me to let Lord Snowdon know (when I’m back in London) that his turbulent love life with Princess Margaret was plainly due to his own excessive indulgence in photography. She confides in me that she has been seriously meditating over the reasons for Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon’s doomed relationship.

And then she addresses me, “Mr Photographer, you better watch out for yourself; too much photography might turn you into a subject,” as she leads me to the main reception room. With an exaggerated, wide sway of the arm, she grandiosely gestures me to a space besieged by dust-covered soft toys, the floor teeming with dead cockroaches and old photo albums with pictures staring back at you, while a TV set rolled out on the floor runs indifferently on its own. “This is the ‘third eye.’ My room of secrets, you know. This room is a chest of secrets, just like me. There are many secrets lurking deep within both of us, in the depths of our souls, that no one will ever know. There’s fear and love in us, and a simmering, deep dark abyss. When I look at the abyss, it looks back at me.

“You see, I haven’t slept since,” her voice trembles, as I wonder if I’d be allowed to visit the upstairs portion of the house. “Ah, the upstairs,” she smiles. It is a long saddened, ironic smile. “Upstairs is the aftermath. All ashes.” Roohi Bano had set the upper storey of the house alight a while ago, I am told.

“When you live among insensitive beasts and vultures who feed and feast on you but who can’t notice your pain, then sometimes you have to use special means to make the pain visible, you see. Whether, it’s leaping out of a window or crying.

“There’s something going on within me, and it is beyond me. I am scared not only for myself, but sometimes of myself,” Roohi Bano sits on the staircase, compulsively scratching her head. In her pain and isolation, she has freed herself from a certain bondage, gained a certain strength to seamlessly sway into the mystery of things.

I finish the shoot. It is time to go. I wish not to go, just yet. But as I said, it is time to go, to let go.

“Sorry, I was a bit depressed today. But it is not my soul’s annihilation. Although I feel trapped in a tunnel, I’m quietly planning for a marathon to race out of it at the break of dawn. The only problem is that everyone expects me to adjust myself to this deranged world out there.” Roohi Bano’s words dissolve into hushed sighs as we part.

And for the moment, it’s already dusk, quite a bit of night ahead, until it is another day.

P.S. I am truly grateful to my precious friend and Urdu short story writer Neelam Bashir, for facilitating this meeting and indeed enriching it with her own inspired and inspiring insights.

Photos by the author

This article was originally published in Newsline’s Annual 2015 issue.