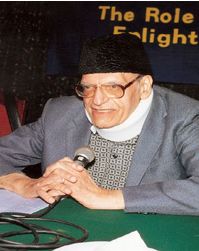

Interview: Dr Fathi Osman

By Shimaila Matri Dawood | People | Q & A | Published 21 years ago

“We are not remaking Islam”

– Dr Fathi Osman

Q: Do you feel there is a need for a reinterpretation of Islamic thought in the modern context?

Q: Do you feel there is a need for a reinterpretation of Islamic thought in the modern context?

A: Yes, I believe that a reviewing or rethinking of the classical sources — even if they are literary — is essential. We have new interpretations of Shakespeare, so why not of the Quran? One of the points in formulating the Quran and in the Sunnah, is that the language can allow for different translations, and in putting the text together, we may have different angles. All this is in addition to the most dynamic factor — which is human thinking. The Divine revelation is permanent, unchangeable — but the human mind that interprets it is always changing according to socio-cultural change.

We are now thinking of the Quran in a new light. For example, in the earlier centuries, the verse on Shura, or consultation, was taken to mean consultation in a closed room. Now we think it is the rights of the masses in sharing, or directing the policies of the country. We get this from universal experience, ideas of democracy, and human rights, etc. Free thinking is very important and I believe we are going through it now. We may not be aware of it, like passengers in a plane who are not able to judge how fast they are travelling. But I think, especially over the last two or three years, we are reviewing everything according to the variables of the world.

Q: If a reappraisal of Islam gained impetus post September 11, is the Quran being reinterpreted just to conform to western values?

A: I think that September 11 was like the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope, or the entry of Sultan Mohammad into Constantinople, the defeat of Antonius in Alexandria, and the conquest of Britain in Gibraltar. Ever since it happened, I said it would be a turning point in the historical relations of the world and the pace of change in the world, especially for the Muslims.

Q: So 9/11 was good for Muslims, in a sense?

A: It is good and bad. It is good for pushing Muslims forward and hastening the momentum of change, but it is bad in terms of the increased paranoia — in always thinking or blaming the ‘others.’ The Muslims always try to make themselves look innocent — they believe they are always the innocent party. This is the negative side.

Q: You have stated, “While the western media does have biases and makes misrepresentations of Islam, this is due to ignorance or lack of information and knowledge, not necessarily due to bad faith.” But isn’t the western media controlled by certain vested interest groups who have an agenda against Islam?

A: We should expect that there might be an agenda against Islam. But if we respect the freedom of others in being against us, and in a variety of public opinions or in differences in opinions in any western group, we should not be scared of attacks against Islam or Muslims. We should expect that people may not like us, either because we cannot express ourselves in a good way or because of their own barriers. If we have self-confidence, we should not care. Some of us are also very bitter against them over trifling things. We need to have self confidence, and only then can we prove who is right and who is wrong.

Q: But Muslims have been labelled terrorists all over the world.

A:I think we need to present ourselves to the world in a convincing way. We need to ask ourselves what went wrong in terms of presenting our beliefs. We need to rethink and represent.

Q: You are staunch advocate of improving ties between Islam and the west. But is it plausible to believe that the gap between Muslims and the western non-Muslim world will be bridged in light of Huntington’s clash of civilisations theory, which the majority of Americans subscribe to?

A: I don’t believe in the clash of civilisations. Civilisation is global and human and this theory tries to restrict what should not be restricted. The mainstream in America is influenced by short term politics, not the long term. They saw Muslim terrorists. So in the short term they believe in confrontation with the Muslim fundamentalists or terrorists or whatever you want to call them. The majority of American society is not politicised, unlike European society. Their concerns are about football or movies or entertainment. The minority shapes the political destiny of the US. This is very serious because when the US became world leaders, they did not share the same understanding as France or Britain. America’s knowledge is from the CIA. So America has its limitations. People may believe there is a danger from Muslims, but in the long term this is not the way forward.

Q: Interestingly you yourself have just used the word “fundamentalist.” Do you think it is an acceptable term and does it not imply a belief that the fundamentals of Islam are violent or abhorrent?

A: I prefer to call this literalism — to be imprisoned in letters. Every religious person cares about the fundamentals of his religion. But when you imprison yourself in certain letters — like the Christian fundamentalists in their belief in the Armageddon or the next coming — it is a serious and dangerous matter. Being imprisoned in letters is the problem — it is static thinking. We need to have dynamic thinking with regard to our religion and reforming it and our development. I think it was well elaborated by Iqbal in the ‘Reconstruction of Islamic Thought.’ I believe that the principals of Islam are good for all society if we draw the line between what is transitional and what is permanent in Islamic sources. What was meant for Arabs would not be convincing now for the rest of the world. For example, why does every Muslim now believe that slavery is not permissible, even if it is in the Quran? It was historical and applicable to that time only. Tribalism — the principle that a leader should be from the tribe of Quraish — also cannot be applied now.

In Christianity, we had Christian reform. In Islam, reform is a hated word. But we need to form again, restructure our priorities, our principles and teachings in order to be convincing to others.

Q: If you believe that the Quran needs to be reinterpreted, have all the great Arabic scholars deliberately misinterpreted the Quran?

A: It is not deliberate, but every commentator of any text is influenced by his circumstances, private and socio-collective. That’s why we had many commentators since medieval times. One commentator may change his opinions from one time to another. We find that Imam Shaafi’s views changed when he moved to Egypt from Iraq. This is just one person, in one generation. What about people in different times and places? Most of the jurists have been men who lived in a patriarchal society, in which a man was everything. To think that a man should be nice to a woman is not the same as thinking she should be equal. Muslims, for example, used to believe that they should be nice to non-Muslims, not that non-Muslims were equal, because they were not a real part of society, but existed as a supplementary component. Today we believe that everyone is equal. Until now, many Muslims cannot draw the line between niceness and equality. You may be nice to your cat or dog but you cannot be equal. So this is one of the main changes in modern thinking of Islam — how to be dynamic not static.

Q: But early Islamic jurists proclaimed that four schools of thought were binding on Muslims for all times. How will it be possible to open the doors of ijtihad, relating the Quran to the modern world, if Muslims scholars themselves are badly funded, divided and lack consensus on the subject?

A: Ijtihad is essential in Shariah, as the Quran is for all time and the needs of people change. The only way to understand it and implement it is human effort. So ijtihad is continuous. Of course, the outcomes will be different. We can have different ways of ijtihad. We need to secure individual ijtihad. We should also organise collective ijtihad in academies and institutions. In our complicated life right now, the jurist needs input from sociologists, social scientists, economists, lawyers, physicists, biologist and doctors, for example, with regards to cloning or organ implantation, etc.

Q: Do you think there is any competent authority today capable of such an exercise in Pakistan?

A: Yes, I believe so. We complement one another now. The image we have of a mujtahid – one who should be like Abu Hanifa or Imam Malik – is impossible. We are used to teamwork now. We can have academies and institutions in which many people work together. We cannot rely on an individual genius like Mohammad Iqbal. Even in political parties, a Quaid e- Azam or a Liaquat Ali Khan, for example, are rare. The Muslim world, however, likes charismatic people. So one may be needed in the short term, and may Allah grant us such a person. But we should rely on gearing our mentality and our expectations to organised teamwork.

Q: But there are serious differences between a scholar such as yourself, for example, and the Pakistani ulema.

A:One of the problems for me with Pakistan and with its Islamic thinkers, is polarisation. One finds very liberal thinkers and others who are very conservative. I find that dialogue and consensus, because of the presence of the two extremes, will be difficult to achieve. In the Arab world, this might have been a challenge a century ago, but Arabia is a tiny society in comparison to Pakistan, which has a huge population. It will be difficult for any reformer to create harmony between the two extremes.

Q:Maulana Maudoodi, for example.

A: Yes. He was very patriarchal in his thinking. We now know that the vast majority of the hadith were not authentic in the sense that they referred to Arab culture rather than what the Prophet (p.bu.h) said. Hadith became the lens through which the Quran was seen. The discipline of Tafsir, or the interpretation of the Quran, was developed afterwards. The difference between original texts and tradition has been merged. Iqbal tried to separate this.

Q: The Pakistani ulema’s understanding and application of Islam with respect to the blasphemy laws, the Hudood Ordinance, etc., has been very rigid. How can the misuse of such laws be tackled??

A:One of the problems of contemporary Islamic thinking is that one doesn’t draw a line between historical practice and the original sources, which are Divine and unchangeable — and sometimes, even with regard to the sources themselves. The message of Islam came to the Arabs at a certain time, place and circumstance, in order to reform the people and reach the world. At the same time it has a universal message. But where can we draw the line between what was meant for the Arabs and what is meant for the whole world? It is a real challenge, because one of the problems with regard to the penal law of the Hudood is that it is part of socio-economic reform. We should not consider Shariah as just punishment or penalties. We have to look at how the society developed, its economy, its education, its systems of justice, etc., before we can punish. The penal law is not just punishment, but also the rights of the defendant. We never talk about the latter. The prescribed punishments need to be considered within the historical circumstances of Arabia — the first central government within a tribal society. At the time there was no police, no prisons, etc., — the only deterrents to crime were these punishments. And these harsh punishments were inherited from other sources. For example, stoning to death was taken from Jewish law in the Bible, and the cutting of hands for theft was widespread in Arabia before Islam. At the same time, a feeling of the harshness of the punishments was there even in the time of the Prophet (pbuh), who made the execution of such punishments extremely difficult. If these punishments were normal and were to be applied over a wide scale, why would the Prophet (pbuh) try to dissuade people from confessing to adultery, or that there need be four witnesses to prove it? We should talk about how we should stop crime, not how we should punish it. Even in the classical works of jurisprudence, if you repent, nobody can punish you.

Ijtihad has been practised individually so far, as we have no collective institutions. Legislation or political development has not gone side by side with intellectual development. In Islam, I am afraid that the so-called Islamic resurgence was not guided by intellect, but by the masses as a reaction to colonialism and the loss of an Islamic identity. When Islam came to be a political power, the lack of the mujtahid or intellectualism was clear. The masses want Islamic law, but how to implement it is not clear.

Q:But embedded in the principles of Islamic jurisprudence, as set by the Hanafi and Shaafi schools, is that the Quran can be divided into two parts: Qathi dalala or revelation that has a fixed meaning and is not open to ijtihad, and qathi thabooth, the parts that allow a difference of opinion. You disagree?

A: The only part in which ijtihad is not applicable is faith in one God and the hereafter. I still say, that the concretisation or conceptualisation of this may change. Someone can argue that this is in spiritual context and there will be no physical resurrection. One cannot term a person who believes this as not being a Muslim. So, although there is no ijtihad in faith or acts of worship — how to pray, etc., — there is room for it on a conceptual level. For example, if I work in a factory and cannot go for prayer, can I pray after work? The area which has no ijtihad is very very small and restricted to aqeeda or faith and some acts of ibaddah.

Q:If there can be no finality in Quranic interpretation of any verse, how can Shariah ever be implemented?

A: By legislation and by majority. There is a difference between individual and institutional ijtihad. When ijtihad is made into legislation, the legislation will be enforced. But we will encourage individual ijtihad and differences in opinion. When the majority agree, there is security, as there is less room for mistakes.

There is a difference between ijtihad as an intellectual practice and ijtihad for legislation. As soon as ijtihad is practiced by people of authority, it will gain legitimacy. The ijtihad of Caliph Omar, which was enforced, is not the same as the ijtihad of Abu Hanifa, who could not enforce what he thought except through his disciples. Legislative ijtihad will be law and enforced within a country. The ijtihad of the parliament of Pakistan, can be different from the ijtihad of Bangladesh.

Q:What do you understand by the term “enlightened moderation?” Is it just an apologist term coined by President Musharraf to serve political purposes or is it based on the fundamentals of Islam?

A: I believe that it is just rephrasing the essence of Islam. The essence of Islam is enlightened moderation — not moderation in general. Sometimes moderation is not recommended as one needs to be steady and firm, and the term enlightenment itself is also vague. But we need ‘enlightened’ moderation – to be moderate according to certain enlightenment – the enlightenment of Islam, historical development and practice. Moderation in itself can be a failure. I believe this is very Islamic — the only problem is that turning this into a programme in the Pakistani context will not be easy. Words are easy but actions are not, especially when there is so much polarisation.

Q:Over 50 international and local scholars were invited for a consultation in Islamabad, including President Musharraf, to discuss their vision of Islam. What conclusions were reached?

A: The consultation was selective. Dr. Riffat Hassan chose people who had differences but also who enjoyed a level of agreement. That is why it was wonderful. I was afraid that we would spend all the time fighting with people from opposite viewpoints, but she chose people with common grounds who had differences only in details. Some of them were from diplomatic circles, some came from academia, others were activists, and both old, retired people and young ones participated. The consultations were very fruitful, and what came out of it was the idea of forming an institution. It would be marvellous if we had an institute for contemporary thinking. We already have private institutes like the one I have in Los Angeles, where I live, but they are all private and their activities are limited. If we can get the support of a country like Pakistan, which has a lot of educated people and scholars, and is a centre of industry and science, it would be something. Qualitatively and quantitatively it would be effective all over the world.

Q:What would the goals of such an institute be?

A: Rethinking the Muslim individual, state and society in modern times. I prefer the term ‘Muslim’ not ‘Islamic’ as Islam makes everything holy and complicated – as if it is ordered by God. We are not remaking Islam. We are not prophets. But something went wrong with the Muslims. This is something we need to ask: What went wrong? We do not want to admit our mistakes, we blame the west, our enemies, Zionism, etc., but not ourselves.

Q:But can an initiative without the more orthodox or traditional scholars, who were excluded from the consultation, be meaningful?

A: Of course we should include them, to try to involve them in committees or institutions, but there are different ways to do so. They shouldn’t be able to engender conflict or to make any developments impossible. We need to pick up the most reasonable or the most promising people to make them the nucleus of change. I was involved in the reform of Al Azhar university in 1961 — trying to secure the integration of education and to end the duality between the religious education and public education by allowing students of secular and public schools while allowing students of religious secondary schools admission to Cairo university. This integration was not welcomed by the professors of Al Azhar. But we benefited from the charisma of Nasser who could enforce it. So now we have a medical school and one of science and agriculture at Al Azhar. But even now Al Azhar is reluctant to accept students from secular schools and its vice versa with the University of Cairo and Alexandria.

Q:Do you think that someone like President Musharraf can bring about ‘enlightened moderation’?

A: I hope so. People may say that Nasser damaged Al Azhar, but I believe that he did a very useful thing with regard to the socio-cultural development. The principal of integration was achieved and this is very essential.

Q:There has been a lot of Western pressure post 9/11 to sway people away from militant jihad to an intellectual and moral jihad. Do you agree with this understanding of jihad?

A: I am for this. I have a book on the subject that says that in our time, political and informative jihad is needed as militant jihad is very destructive. Governments, according to their technological developments, can crush any movement. Also militants can cause a lot of damage by suicide attacks and car bombs, etc., and innocent people suffer. In Iraq, those who haven’t been killed by American bombs have fallen victim to suicide bombs. So I believe that militant jihad will not work, and that it is an outcome of static mentality. In the 19th century, we thought we could change things through these efforts, but the situation now is different. We have big governments and big armies who can paralyse any opposition. Defence is not possible through destructive means. We need to turn to civilised arguments. Of course this will not be easy.

Q:But doesn’t the Quran state that opression is worse than slaughter and does it not give legitimacy to fighting against an enemy through military means?

A: Fighting whom? In a historical context it was fighting those who kicked Prophet Mohammad (pbuh) out of Mecca and those who oppressed his people and put a stone on the chest of Bilal. These people used their military power and initiated the fight. So the Quran asked Muslims to fight back. We should not take this out of context and think that this is a permanent order for all Muslims at all times and in all places against all other non-Muslims. This is a big misconception. Islam never declared a war against all non-Muslims all over the world for all times.

Q:But isn’t Quranic revelation applicable to all times?

A:No, no…yes it is for all times, but it is clear according to the words themselves, that it is directed against certain people. As I said, in the Quran, certain things apply only to that society and deals with events there, but some things are universal. Let’s talk about the Bible. We have the ten commandments, one of which is not to kill, while Joshua burned animals during his war. But what Joshua did was temporary, while the ten commandments were universal. It is the same for every religion that is thousands of years old.

Q:There is a perception that some Muslim ulemas have been bought by the west.

A: No, I don’t think so. People are confused. Some of the ulema may be confused in trying to reform things that are superficial, and others may not agree with reform at all. So there may be some prescriptions from the west, for example, Islamic schools are a problem, don’t memorise the Quran or verses of jihad, apply democracy and reform the education system. But we need to reform according to our feelings, think about what we suffer from. We should not accept outsiders and their presecriptions even if we respect them and believe in their good intentions. We need to be most serious about concerning ourselves with reforming our own situation.

Dr Fathi Osman is a renowned scholar of Islam, Muslim intellectual development and the contemporary Muslim world. He has taught at prominent universities in the Middle East, Asia and the west. He is presently Scholar in Residence, Institute of the Study of the role of Islam in the contemporary world, Omar Ibn Khattab Foundation, Los Angeles. He has written more than 25 books in Arabic and English, such as Islamic thought and change, and Jihad: A legitimate struggle for moral development and human rights. He was also editor-in-chief of a London-based journal, Arabia: The Islamic World Review.