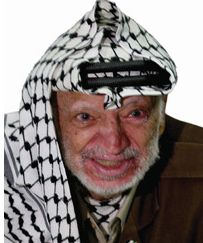

After Arafat, What?

After Yasser Arafat finally lost his battle against the Grim Reaper in a Paris hospital last month, there was certainly a lot of grief in the Palestinian territories and among the diaspora, but in most cases the sense of personal loss was compounded by a heightened level of angst. Behind the tears lay the vacant looks associated with freshly orphaned children compelled to contend with not just the sorrow of being permanently parted from a beloved parent but also the uncertainty that lies ahead.

All Palestinians are, of course, accustomed to uncertainty: they have known nothing else all their lives. But Arafat — or Abu Ammar, the nom de guerre favoured by his compatriots — provided an anchor to which they could cling. He devoted his life to conjuring up a ship of state to which that anchor could be attached. The quest was foiled at every step by designated foes and counterfeit friends.

The enemies are now saying that, with Arafat out of the way, chances of Palestinian statehood have brightened. Ariel Sharon designated Arafat an obstacle to peace, and that stance became an excuse for suspending all negotiations. The Bush administration, peppered as it is with Likudites, takes it cues from the Israeli regime. It too refused to have anything to do with Arafat, insisting that all Palestinian attacks on Israelis must stop before any talks could take place. There was no comparable pressure on Sharon: even when the systematic violence unleashed by his forces on defenceless Arabs went so far that the State Department was compelled to describe it as “regrettable”, it diluted that timid critique by saying that it was nonetheless “understandable”. Any criticism of Israel at the UN Security Council automatically prompted an American veto.

Arafat unquestionably personified the Palestinian cause to an extent that has few parallels in other 20th-century national liberation movements. He was one of the movement’s most important assets, but perhaps also one of its major liabilities. Chances are that the cause would have evolved even without him — although such has been his role that it is impossible to say what shape it would have taken. By the same token, the cause hasn’t been buried alongside Abu Ammar in Ramallah. But it’s not in the best of health. And the barely restrained glee of Israeli and American leaders at Arafat’s departure suggests they expect to benefit from it.

Arafat’s existence made it impossible for those two countries to pick a Palestinian leader who would accede to their wishes. Arafat came a long way, but from the US-Israeli point of view, he wasn’t prepared to go far enough. Washington and Tel Aviv wanted someone even more pliable, but as long as Abu Ammar was a candidate, no rival seriously stood a chance in any election. Now they are counting on Mahmoud Abbas, Arafat’s successor as leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation, to win the election for president of the Palestinian Authority scheduled for next month — and, subsequently, to sign away some of the Palestinian rights that his predecessor refused to compromise on.

There is no guarantee that Abbas will triumph in any electoral exercise, but even if Abbas is victorious and thereafter willing to accommodate most US-Israeli wishes, what are the chances he will be able to convince his people that he has done the right thing?

When, back in 1988, Arafat spearheaded the Palestinian National Council’s recognition of Israel and acceptance of a two-state solution, he threw himself open to a great deal of criticism — but by then he had managed to persuade the majority of Palestinians that this was the best they could hope for. He had recognised as early as the 1973 Yom Kippur war that Israel could not be defeated militarily, and that the PLO’s demand for the restitution of a Palestine in which Jews, Christians and Muslims could live side by side was an impossible dream. It took him 15 years to gain the confidence that he could carry the movement with him.

The Oslo Accords also occasioned a great deal of flak, with Arafat accused once more of betraying the cause. It was a big risk, and gaining statehood in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip — barely 22 percent of historical Palestine — would barely have provided adequate post-hoc justification for taking it. In that Arafat failed, and the US-Israeli line is that it was foolish and perhaps even unforgivable for him to have turned down the proposal placed before him at Camp David by Ehud Barak, under the auspices of Bill Clinton, in 2000.

That view bears little relation to the facts. Under the terms of that proposal, not only would Arafat have had to sign away the right of four million Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, but also sell to the residents of the occupied territories the idea that the West Bank would be divided into cantons by Israeli corridors, and that most of the Jewish settlements built in the territories in defiance of UN resolutions would stay — with Israel taking care of the security arrangements.

The bantustans option, Arafat knew, would lead to a protectorate rather than a viable independent state. The US and the Israelis decried him as an unreasonable spoiler who had squandered the best chance for peace in the Middle East, but he received a hero’s reception on his return to the territories. Arafat was never in any doubt about where his obligations lay. Criticism of his ineptness at the helm of an administration riddled with corruption and cronyism isn’t inapt, but it’s worth keeping in mind that he laboured under impossible conditions, and the Palestine Authority has never amounted to much more than a glorified municipality, which has consistently been under enormous pressure to crack down against secular as well as Islamist radicals.

If Israeli-Palestinian negotiations resume, chances are that the offers on the table will be even less generous than Barak’s. Not long ago, a top Sharon aide confessed that the plan for a unilateral Gaza pullout was intended to halt rather than accelerate the peace process. The powers that be now hope to bully Arafat’s successor into effectively signing away the Palestinian right to meaningful independence. Colin Powell lost little time in heading for Israel after Arafat was gone (although the US was represented at a considerably lower level at the Palestinian leader’s people-free funeral in Cairo), followed by Jack Straw, and Tony Blair is expected in the Middle East before Christmas.

Blair was relatively less ungracious than Sharon, George W. Bush and their pathetic little Australian acolyte John Howard in their comments on Arafat’s demise, and a substantial portion of the British Labour Party is inclined towards Europe’s more reasonable stance on the Palestinian issue, but the UK is unlikely to defy the US, where Likudites hold sway. Which means that Palestinians, including those who felt let down by Arafat, may soon have cause to miss Abu Ammar more than ever.

Arafat’s legacy extends far beyond the frustrating last decade of his life. The iconic keffiyeh and three-day stubble were an affectation that dated back to his youth, and he described himself as Mr Palestine long before he led the defence of the Jordanian town of Karameh in 1968 and instantly acquired the status of a legend. Two years later, the PLO — founded by Gamal Abdel Nasser as a means of controlling rather than bolstering the Palestinian cause, and taken over by Arafat’s Fatah faction only after a lengthy power struggle — found itself besieged by the Jordanian army, which was assisted by a Pakistani contingent led by a certain Major Zia-ul-Haq.

Arafat lived to fight another day when Israel invaded his next base, Lebanon, in 1982, and again when Israeli terrorists wiped out much of the PLO’s leadership in an unprovoked attack on Tunis a few years later. If his foes were never convinced by his conversion into a peacemaker, that’s largely because they never stopped subscribing to the idea of a Greater Israel. They wanted to believe what Golda Meir had told them: that there’s no such thing as Palestinians. Arafat proved them wrong, and they never forgave him for it.

What endeared Arafat to the Palestinians, more than anything else, was that he had suffered alongside them every step of the way. Of course he had his flaws, but that didn’t prevent at least some Israelis from recognising his worth. And the respect was reciprocal. Shortly before he was assassinated by a Jewish fanatic, Yitzhak Rabin described Arafat as “my partner”. An American diplomat recalls that Arafat cried like a baby when he heard of Rabin’s murder.

In death Arafat has attracted worthy tributes from across the world; Jacques Chirac offered an eloquent eulogy, and the UN flag flew at half mast. Perhaps some of the most heartfelt comments came from those who knew only too well what it felt like to be denigrated as a terrorist: Nelson Mandela and Gerry Adams. But the tribute that might have mattered most to Arafat came from an Israeli who understood Arafat’s passion, who respected his soul. “I respected him as a Palestinian patriot,” wrote Uri Avnery. “I admired him for his courage. I understood the constraints he was working under. I saw in him the partner for building a new future for our two peoples. I was his friend … As Hamlet said about his father: ‘He was a man, take him for all in all. I shall not look upon his like again.’”

Mahir Ali is an Australia-based journalist. He writes regularly for several Pakistani publications, including Newsline.