Canvas Without Borders

By Sadaf Halai | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 19 years ago

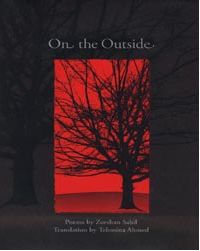

If Zeeshan Sahil’s poems were paintings, they would be monochromatic, abstract compositions interrupted with surprising alacrity by an ordinary household object. With one foot in the abstract realm and the other planted firmly in a world of concrete things, Sahil’s poems shift comfortably between worlds both real and imagined. Reading Sahil’s poetry is like piecing together a mysterious and broken message. The diction of his prose-poetry is spare, but the content heavily metaphorical. On the Outside, a collection of fifty poems selected from his seven volumes of poems, has been translated by Tehmina Ahmed. These poems, in translation, appear simple on the surface, in that the diction is uncluttered and precise. However, a closer examination reveals a complex multiplicity underneath the seemingly straightforward narrative. This tonal shift is best characterised by the poem “The Jungle” (Yaad):

“remembrance

is a heap of

autumn leaves

flowers that have withered

of ice and sand

thisi do not know

but a child tells me

and filling his pistol

squirts the heap

with water.”

Critiquing prose poetry is not a simple matter. The genre does away with much of the formality of metered verse, and for this reason, it has often been derided by purists. In many ways, Sahil’s poetry provides the kind of work translators dream of. A common caveat faced by the translator is whether or not to remain true to the poetic form and structure of the original poem. The absence of end rhymes in the Urdu original of Sahil’s poems allows the translator the advantage of a canvas without strict borders.

As with any poetry translation, something of the original is lost along the way. This is particularly true of translating Urdu poetry into English. In the poem On the Outside, Sahil writes “Mujh say bahir aik jangal hey / jahan patton ke girnay ke liye / koee khas dhun ya mausam mukarrar naheen.” These particular lines have been translated to “Outside me / there is a jungle / where there is no particular season / for the leaves to fall.” It is traditionally up to the translator’s discretion what matter is to be left untreated from the original. The omission of the word “dhun” presents a problem unique to translation; the connotative value of a word like “dhun” may not have an English equivalent that would be true to the tone of the original. “Melody” and “harmony” would not be in keeping with the poem’s pessimism.

In terms of grammar and structure, all of Ahmed’s translated poems are written in the lower case, the line lengths are true approximations of the Urdu originals and, with a few exceptions, the number of stanzas is also consistent between the English and the Urdu. More importantly, the wryness and emotional flatness of the original has been captured by the translation. Sahil’s poetry is exemplified by dissociation from the external world and the voice of the poem is, more often than not, quietly resigned to the state of things in the external world. “Mujh say bahir aik jangal hey / jahan har shaam / mein darakhton ke darmian / dhoop ko aakhree baar dekhta hoon / aur bahir nikl jaata hoon” (“there is a jungle / outside me / every evening / I watch the sun set / among the trees / for the last time / and leave” — “On the Outside”) writes Sahil in Mujh Say Bahir, the title poem of this collection.

In a paper on translation, Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney said: “For all the satisfaction that a cabinetmaker gets from the wood and all that, he still probably feels, ‘It’s not really mine when I finish it, it belongs to it, to the wood,’ it is it again. And I think that in a verse translation there is a similar attempt at restitution. It is an homage, an attempt to redo the cabinet. You are given a shape and you try to shape up.” The greatest achievement of On the Outside is that it makes a tremendous effort to remain true to the original, and demonstrates that it is possible to translate from Urdu to English provided that the translator’s own voice does not obstruct the poetic content of the original. In this respect, it is a successful enterprise and, like any well-crafted work, it belongs wholly, and ultimately, to itself.