Don’t Look Now

By nolasco.moniz | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 18 years ago

There was a time not all that long ago when blood and gore, hangings, decapitations and the like were more often heard about than seen. The evening news on television did not generally turn your dinner into ashes inside your mouth. If those were more innocent times, it’s not because there was less mayhem all around us. It’s just that visual evidence of it was harder to come by. Information technology has advanced by leaps and bounds over the past few decades, completely revolutionising the way many of us look at the world.

A dozen or so years ago, the mobile or cell phone was a brick-shaped novelty that enabled you, if you were well positioned, to make and receive calls. Now most models incorporate a camera, a video screen, a music player and a radio, and they fold into the palm of your hand. An extremely convenient and reasonably innocuous device, one would have thought. Who could have imagined that it would play such an instrumental role in enhancing, arguably, the brutalisation of society.

Much the same could be said about the World Wide Web. Hundreds of millions of people across the world would feel a little lost without internet connectivity. In its early years, the internet spawned fears about access to pornography in its most insidious forms. Unlike most other media, the net was hard to censor without undermining the libertarian anarchy that provides part of its raison d’etre. There have, however, been crackdowns in some countries on those dabbling in child pornography, and in recent years the issue of sex sites has receded as an area of concern in the West.

This tendency may not be unrelated to the so-called war on terror: the defenders of morality suddenly discovered that they had more important things to worry about. During the same period, another form of pornography made its debut on the net: extreme violence, including graphic scenes of cold-blooded murder.

Unlike much of the sex, the violence wasn’t simulated. Thus was the cruel fate of the American journalist Daniel Pearl certified. And Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian terrorist killed in Iraq last year, allegedly relished the idea of broadcasting his deeds: from hostages pleading for their lives to heads being sliced off. Somewhat sanitised versions of such video clips found their way into television news footage, while the director’s cut, so to speak, could be found on Islamist websites and elsewhere on the internet.

It’s hard to say whether the grisly visuals were indeed intended as a jihadi recruitment tool, although video footage of the aftermath of suicide bombings has undoubtedly been used towards that end. It’s a dreadful thought, but presumably it exercises some sort of attraction for those with a particular mentality. Death — their own and those of others — evidently becomes an obsession for some of those who can discern no other purpose in life.

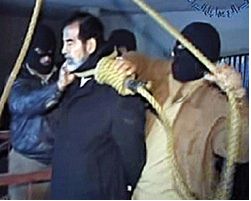

Such images are also meant to play another role: to serve as a warning, a threat, or possibly a deterrent. That was among the reasons behind the decision of the Iraqi authorities to broadcast footage of Saddam Hussein’s execution, which was also intended, inter alia, as a pre-emptive strike against speculation that the hanging may have been faked. As a result, television audiences around the world were confronted with the sight of an elderly man with a noose around his neck, in the moments before he was killed. Not everyone appreciated the image, regardless of the impression they had of Saddam’s career as a dictator.

The official version of the video was released without a soundtrack. Within hours, an unauthorised version surfaced, evidently shot via a mobile phone. It showed that some of those present at the execution betrayed the mentality of a lynch mob by taunting the condemned man, who responded firmly but calmly to the provocations, maintaining a dignified posture throughout the proceedings; he refused the offer of a hood. It also showed that he was halfway through the kalima when the noose tightened around his neck. Shortly before, upon being told to go to hell by one of his tormentors, Saddam had responded with a terse and truthful, “But Iraq is hell.”

The official version of the video was released without a soundtrack. Within hours, an unauthorised version surfaced, evidently shot via a mobile phone. It showed that some of those present at the execution betrayed the mentality of a lynch mob by taunting the condemned man, who responded firmly but calmly to the provocations, maintaining a dignified posture throughout the proceedings; he refused the offer of a hood. It also showed that he was halfway through the kalima when the noose tightened around his neck. Shortly before, upon being told to go to hell by one of his tormentors, Saddam had responded with a terse and truthful, “But Iraq is hell.”

To many of Saddam’s detractors in Iraq and Iran, none of this seemed to matter: they made no secret of their joy at his dispatch. Through much of the Arab world, however, it redeemed Saddam somewhat, even in the eyes of those who had never thought much of him previously. Vociferous condemnation of the depicted proceedings in most of the western media compelled a reluctant George W. Bush and an even more hesitant Tony Blair to criticise what had occurred. The Americans have made a concerted effort to distance themselves from the circumstances of Saddam’s execution, the spin being that it was entirely an Iraqi affair — never mind that it was followed within 10 days or so by yet another demonstration of the nation’s colonial status.

Some days after the hanging, further footage emerged, showing the deceased dictator with a large gash in his neck. When, some two weeks later, it was decided to execute Saddam’s co-accused, his half-brother Barzan Ibrahim Al Takriti and former chief judge Awad Hamad Al Bandar, the authorities made sure there were no mobile phones in the execution chamber. That’s probably just as well. The hangman allowed for more than enough rope. Too much, in fact. As a result, Barzan literally lost his head when the lever was pulled.

The official footage of his apparently inadvertent decapitation was supposed to have been seen only by a handful of officials and a select bunch of journalists. It would never, Baghdad officials said, be released to the public. Within days, however, copies were posted on YouTube, the website that allows users to upload video clips of more or less everything. The visual evidence wasn’t really necessary: news reports had sufficed to exacerbate the deepening Shia-Sunni divide that is having repercussions far beyond Iraq.

In the case of the unauthorised Saddam video, the puppet regime in Baghdad reacted to the international uproar by arresting one of the officials believed to be responsible for shooting and distributing it — as if it was the audio-visual evidence of tawdry manners that was the problem, rather than the behaviour itself. The reaction wasn’t all that different from the way US military authorities responded in the wake of the embarrassment and outrage caused by the publication of photographs depicting the torture of inmates at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison a couple of years ago. They banned cameras from the premises. No one outside the chain of command can be certain whether the appallingly humiliating behaviour depicted in those images has been modified: what we do know is that it is not being unofficially photographed.

The Abu Ghraib images were leaked by a whistleblower. The ones that saw the light of day were harrowing enough. However, the worst of the lot were never published. They were shown to members of Congress, a few of whom wanly confessed that they were far worse than anything that had been made public. The latter sufficed to make many Americans reconsider their support for the war in Iraq. Although Donald Rumsfeld and his minions did their best to create the impression that only a bunch of rogue interrogators were responsible for the depredations depicted in those photographs, the Abu Ghraib exposé was when the tide of public opinion began to turn in the US.

The Abu Ghraib images were leaked by a whistleblower. The ones that saw the light of day were harrowing enough. However, the worst of the lot were never published. They were shown to members of Congress, a few of whom wanly confessed that they were far worse than anything that had been made public. The latter sufficed to make many Americans reconsider their support for the war in Iraq. Although Donald Rumsfeld and his minions did their best to create the impression that only a bunch of rogue interrogators were responsible for the depredations depicted in those photographs, the Abu Ghraib exposé was when the tide of public opinion began to turn in the US.

This was reminiscent, in some ways, of an earlier era. Back in 1969, splashed across the pages of Life magazine, images from My Lai — a South Vietnamese village where a company of US troops killed almost everyone in sight, the majority of them women and children — chilled large numbers of Americans. Another notorious photograph of the era shows a Saigon police chief — a representative of the puppet South Vietnamese regime, and therefore a “good guy” from Washington’s point of view — holding a gun to the head of a young communist suspect moments before he pulled the trigger. There were countless others. Richard Nixon refused to accept that his government was losing the war on both fronts: in Vietnam as well as at home. Less than four decades later, another American president is making the same sort of mistake.

There are innumerable instances over the past century of photographic images changing popular perceptions. To cite but one example, back in the 1980s, televised pictures of starving infants in Somalia and Ethiopia helped to kick off a concerted charity drive that has continued to resonate down the years. In fact, the images needn’t necessarily be photographic. It is said that a Nazi officer gazing at ‘Guernica’ — a graphic depiction of the destruction of a Spanish village in a fascist air raid — in a French gallery turned to the artist and asked him, “Did you make this?” Responded Pablo Picasso, “No, General. You did.” In a reflection of the times, a reproduction of ‘Guernica’ that hangs in the UN headquarters in New York was covered up when Colin Powell went to the Security Council four years ago this month to make his infamous presentation about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction.

The Picasso story cited above may well be apocryphal, but it makes a valid point.

Never before have images been so ubiquitous. “A Thousand Pictures Are Worth One Word: Noooo!” was the title of a recent column by the American humorist Art Buchwald, who died last month. “There are now 340 million digital cameras and video recorders in the United States and 123 million grandchildren,” he began. “It is no secret why. Digital camera and recorders give us instant satisfaction. There is a good side and a bad side to this… The downside is that after you’ve taken 1,000 pictures, no one wants to look at them.”

One of the upsides is, of course, that it has become so much harder to keep things under cover. In some parts of the world, almost everyone totes a camera nowadays, and the images thus obtained can travel around the world in an instant. Saddam’s execution is an obvious case in point. Whenever there is a catastrophe anywhere in the world, manmade or natural, websites such as the BBC’s solicit snapshots from the public, and are often able to offer visuals long before professional photographers can get to the scene.

For anyone who browses the internet or channel-hops on the TV, it usually takes a special effort to avoid exposure to images that are harrowing, confronting, or in some way unsuitable for children. The most reprehensible of the lot are depictions of violence that are specifically tailored to encourage more of the same. It is easier, however, to recommend restraint than to encourage censorship, for the latter can easily be misused to restrict access to information.

Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ is a tapestry of horror. And if the artist did put a Nazi general in his place, it was the right thing to do — Picasso did not pluck the twisted images out of his imagination, he merely captured real-life brutality on a canvas. Much the same could be argued by even the least palatable images that greet us in these troubled times. It’s fine to be squeamish: there would be greater cause for concern if nothing shocked us any more. But let us never forget that the images themselves generally pose no threat. It’s the reality behind them that we should strive to change.