Book Review: Paracha

By Deneb Sumbul | Books | Published 10 years ago

Master of the Game – H. M. Habibullah’s life story is the stuff classics and blockbuster films are made of…

By Deneb Sumbul

A boy, the first son, was born into a small-time trader’s family at the close of the 19th century, in a little known village called Mukhad, straddling Punjab and the North West Frontier Province. This was the age of Imperialism, when George Orwell argued that “Emphasis on the difference between ‘whites’ and the natives is necessary for Imperialism.” In that epoch, anyone wanting to emerge from the shackles of poverty, and all it engendered — a lack of social status and little or no education — and from a deeply tradition-bound conservative community, would have to climb very high and far to get to a place of recognition, power and wealth.

A boy, the first son, was born into a small-time trader’s family at the close of the 19th century, in a little known village called Mukhad, straddling Punjab and the North West Frontier Province. This was the age of Imperialism, when George Orwell argued that “Emphasis on the difference between ‘whites’ and the natives is necessary for Imperialism.” In that epoch, anyone wanting to emerge from the shackles of poverty, and all it engendered — a lack of social status and little or no education — and from a deeply tradition-bound conservative community, would have to climb very high and far to get to a place of recognition, power and wealth.

That someone was Habibullah Paracha, of the Paracha tribe, upon whom was later bestowed the much coveted title of ‘Khan Bahadur’ by the British. By then, he had amassed wealth, and was known far beyond the confines of the nondescript village he was born in.

He went from horseback to hydrofoil. And this is his story. As a biography, written by his granddaughter, Nazli Rafat Jamal, it was with somewhat mixed feelings that I started to read… and couldn’t stop. For starters, despite her obvious awe of her paternal grandfather, the author has not tried to paint him as an idol. Although the book is, as Kamal Azfar has written in the introduction, obviously “a labour of love,” Jamal has depicted him as a real-life character: a powerful, ambitious man with foibles and failures. She has been surprisingly candid about Habibullah’s zest for life, his appreciation of beautiful objects and his lifelong love of ‘controlled’ gambling; his admiration of beautiful women; his ferocious ambition to win — regardless of collateral damage — and his controlling temperament, particularly where his family was concerned.

The story begins in 1911, when at age 14, he sets out with his father, Hafiz Muhammad Gul, on horseback from Peshawar to Bukhara, where Habibullah is enrolled for a four-year course at the famous Madressah Ulugbek, built by a son of Tamerlane (Timur). Here, in addition to rote learning, he also learns the art of business, of how to extract the last penny of profit from transactions, by observing his paternal uncle, who stayed on in Bukhara.

In 1911, Habibullah and his father were issued passports from the British Legation in St. Petersburg to enable them to travel to Russia, ostensibly to trade in fur, although they had travelled from Peshawar to Bukhara without formal travel documents. The British Empire at the time covered a fifth of the world’s land and comprised of a quarter of its population. Passports were only issued to men of consequence — and of use. Hence, Hafiz Muhammad Gul must have been someone of relevance to the British. The link is indicated by the implicit reference to the fact that the MI6 was active in the NWFP in those days. They recruited able Indian traders, particularly the hardy, resourceful Silk Route merchants, and trained them as spies to record in minute and unique detail (including weaving maps into carpets) their observations, to help the British estimate Russian intentions and their military capabilities, among other things in their pursuit of protecting their Empire. It was the Great Game and Habibullah was a link in the chain. Ironically, his questionable role proved beneficial for Pakistan decades later, when it was trying to locate and obtain documents and materials for its nuclear programme. The book delves into this in some detail.

Living well and fully — into his nineties — Habibullah’s unique ability to be a witness at turning points of the early and mid-20th century, is a walk through world history — pre-revolutionary Russia, pre-World War II China and Japan, pre-partitioned India, and the first four decades of Pakistan. His life was, “A journey through time and space!” according to Jamsheed Marker, former Ambassador to the US.

By the book’s account, at 18, Habibullah was present on a Tashkent platform when the train carrying the Russian Czar, Czarina and Rasputin made a stop. He saw them from close quarters. He was present in Bukhara during the Bolshevik Revolution and was robbed of his life’s savings by the Red Army. He was in unsettled Iran before the Pahlavis; in Shanghai where he made his first fortune just when the Chinese Communist Revolution started; in Japan where, in Shizuoka, he taught locals the proper treatment of green tea for the Central and South Asian markets, which led to a sharp rise in Japan’s export of green tea. He was even awarded by the Japanese government, but had to flee on the eve of World War II. And he was in Amritsar, where he had finally settled with his immediate and extended family and made a home and fortune for himself, but was forced to leave it all behind in the mayhem of Partition. Ultimately, he was witness to Pakistan’s formative years, when he, a Punjabi, re-established his life in Karachi, served and won over the migrants who poured in, and was elected as Mayor/Vice-Chairman of the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation.

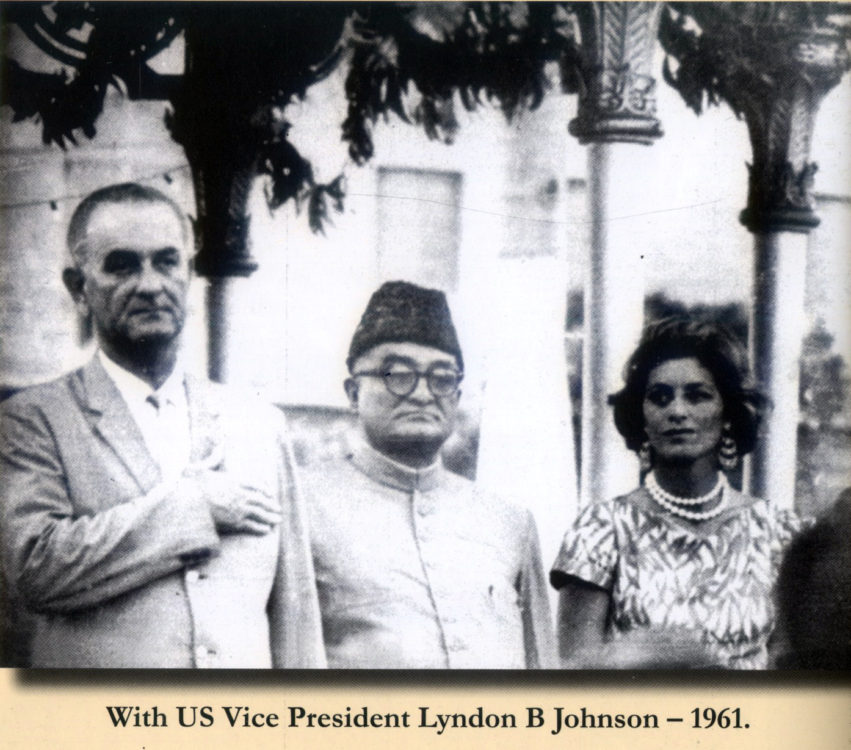

As Karachi was then the capital, in his capacity as Mayor, Habibullah welcomed and entertained heads of state, kings and queens, presidents, prime ministers and other dignitaries. The list included Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, King Zahir Shah of Afghanistan, Premier Zhou En Lai of China, Jacqueline Kennedy, the Shahanshah of Iran, the King and Queen of Thailand, Crown Prince and Princess of Japan, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri of India, and many others. This was the pinnacle of his career and this is what he loved to do. “Each day brought a new set of problems and each problem was a challenge; a puzzle to be solved, a game to be won. It had nothing to do with money; it had everything to do with power and service. His reputation as an honest and efficient administrator was acknowledged, even by his detractors.”

Habibullah’s subsequent foray into setting up textile and coal-mining industries, his passion for politics, his friendship with Ayub Khan; the enmity he incurred of the Nawab of Kalabagh — the most feared man of the time perhaps — for daring to challenge him as an equal (“a nobody, a country bumpkin” in Kalabagh’s words), who twice thwarted Habibullah’s ambitions to get elected to the National Assembly despite Ayub Khan’s backing; his successful stint, in his late 70s, as Ambassador to Malaysia (sent specially by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto); his help, although never clearly acknowledged, in obtaining necessary documents and materials for the government for the country’s nascent nuclear programme; his role in securing Benazir’s release from house arrest — all this Habibullah did under his own steam.

What emerges very clearly is a picture of a self-made man with an enormous physical presence and a ‘force field’ personality; a man who never shared his plans (his family was not privy to many parts of his work and life), a man who kept his own counsel, and whose word was law in his domain.

Habibullah broke free of more than the village. He broke rules and made his own to move forward in life. A Hafiz-e-Quran in just a year by age 11, at age 15, in Bukhara, he arranged secretly to learn English, which was considered sacrilegious by his family — the language of the ‘kafir’ (infidel). He was keenly observant and a quick learner. In Shanghai, he witnessed the plight of the aristocratic White Russians and saw that only those with a professional degree survived. So he vowed to ensure that his children received the best possible education, despite his family background where it was not considered a priority.

He insisted on living large and living generously. There is a very telling episode about when he first returned to Mukhad in 1938, after making his fortune in China. He introduced some novelties — his brand new Buick and the first ever radio set to the village — a talking point for the villagers for a long time afterwards. “Traders from Mukhad had been doing business with China for ages, but no one had brought China to Mukhad as Habibullah did on his dramatic return,” says the author, Nazli Jamal, as narrated to her by her father as part of family lore. “He brought souvenirs by the hundreds and there was something for everyone in the village.”

Wherever he lived, he became an active member of the community — and shared good things, mostly the choicest of seasonal fruits, with others. His shopping was legendary. In a chapter on Habibullah and the family, Nazli has written about his trips to Hong Kong and how he would return laden with suitcases of gifts for his (by then) very large family of wives, children, their spouses, grandchildren, relatives and never-forgotten household help.

There was a downside. As the author narrates; “Habibullah controlled his 10 children and their spouses, with the flair of a chess master…His relationship with his sons was complicated…Intrigues and rivalries were part of life at Al-Habib (the grandiose family home he built in Karachi)…The ‘divide and rule’ policy was applied unabashedly…with no dilution of his own authority…He was the true ‘Master of the Game’…He was prone to favouritism…The Hindu influence on Mukhaddi customs was dominant with regard to inheritance…It was considered enough that the daughter had received a dowry at her wedding…this was a notion he could not shake off, despite his progressive outlook and exposure to the outside world…He relied largely on himself, his offspring only knew what he chose to divulge…He was a secretive person; after all he had had intelligence training.”

There was a downside. As the author narrates; “Habibullah controlled his 10 children and their spouses, with the flair of a chess master…His relationship with his sons was complicated…Intrigues and rivalries were part of life at Al-Habib (the grandiose family home he built in Karachi)…The ‘divide and rule’ policy was applied unabashedly…with no dilution of his own authority…He was the true ‘Master of the Game’…He was prone to favouritism…The Hindu influence on Mukhaddi customs was dominant with regard to inheritance…It was considered enough that the daughter had received a dowry at her wedding…this was a notion he could not shake off, despite his progressive outlook and exposure to the outside world…He relied largely on himself, his offspring only knew what he chose to divulge…He was a secretive person; after all he had had intelligence training.”

Till the end of his life, Habibullah played a role in the nation’s political life. He was instrumental in securing Benazir’s release from house arrest under Zia-ul-Haq’s reign. One of his final outings was to attend Benazir’s marriage to Asif Zardari.

Although, when you read about Habibullah’s failures, they seem to outweigh his gains, what really constitutes a successful life? If it is striving to achieve, and then achieving all one has set to achieve even against insurmountable odds, then Habibullah’s life meets the criteria.

Despite the wealth of detail and information, PARACHA is surprisingly fast-paced and easy to read. The author has summed up the book thus: “I hope it will create curiosity about an era that seems like a fairy-tale now. And about the larger-than-life man who, with unflinching determination to overcome all odds, dared to live an action-packed, wide-ranging, adventurous, and — some would say — charmed life, that is granted to few and only to the brave.”

This review was originally published in Newsline’s December 2015 issue.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.