Back to the Future?

By Tariq Rahman | Arts & Culture | Books | News & Politics | Published 17 years ago

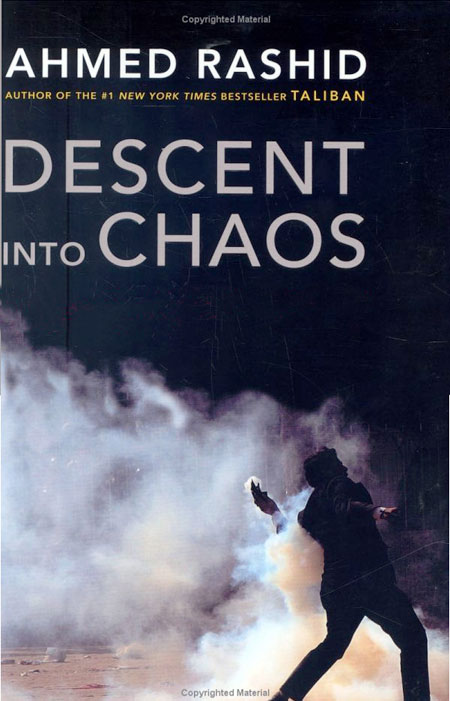

Ahmed Rashid is, arguably, the most famous journalist-scholar from Pakistan because of his books on Central Asia: The Resurgence of Central Asia (1994); Taliban(2000) and Jihad (2002). His book Taliban is probably the most cited work on the Taliban and the politics of oil as it relates to Central Asia, Afghanistan and Pakistan. The book under review is the latest addition to his writings on this volatile region, and promises to become a landmark study on the rise of militant Islam in Afghanistan and Pakistan, as well as the policies, both American and Pakistani, which have made this possible.

The book’s subtitle sums up its theme in a nutshell: ‘How the war against Islamic extremism is being lost in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.’

The book’s subtitle sums up its theme in a nutshell: ‘How the war against Islamic extremism is being lost in Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.’

Ahmed Rashid begins his introduction with 9/11 and his own belief that the war in Afghanistan was a “just war and not an imperialist intervention.” Whether one agrees with this point of view or not (I do not subscribe to it), the rest of the author’s argument — that the United States did not develop this area, resulting in its passing into the hands of warlords and extremists — is correct. Indeed, one does not know of any author who has documented this great betrayal of the Afghan people in such detail and with such an inside knowledge of events and actors as Ahmed Rashid has.

The first part of the book is an elaboration of this thesis. One finds glimpses of Hamid Karzai as well as a number of other people who were politically active during those years. Rashid stipulates that although the Taliban had been defeated, the United States was not creating a unified central power. Instead, the warlords were back with US blessing and Afghanistan was descending into chaos. The drug trade, controlled by the Taliban, was taking root again. The intelligence agencies, both of India and Pakistan, were establishing their hold in the country and their proxy wars were adding to the chaos into which Afghanistan was descending.

In Chapter 2, the author states that the Pakistani military supported the Taliban before 9/11 because of its belief that it could secure its strategic interests in Afghanistan through them. But on September 13, the United States gave Pakistan a list of demands which were ostensibly accepted by General Musharraf. However, according to Ahmed Rashid, the militants were allowed to enter and re-group in Pakistan. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 give details of this “schizophrenia.” As before, the military establishment wanted to use the Taliban to keep its clout in Afghanistan (especially against India) intact. Then came militant attacks on the Indian parliament and the danger of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan. At this time, the author states, General Musharraf did change some aspects of his pro-militant policies — an action which made him their target — but still the Taliban in Afghanistan were not wholly targeted. Chapter 11 gives details of camps in Quetta where the Taliban received help from the ISI in order to re-enter Afghanistan. This chapter is based on Ahmed Rashid’s observations and conversations with people who have knowledge about these activities. Interestingly, Rashid also contends that “for four years, Mullah Omar and his commanders were able to operate freely in Balochistan and southern Afghanistan without being monitored by US intelligence.” This is inexplicable in view of the general perception that America has the capability of keeping a close watch on any part of the earth it desires. If true, the oversight by the Americans appears to be the height of folly for US policy-makers.

Also surprising, but reassuring, is Rashid’s view of the huge enthusiasm in Afghanistan about elections. Even women stood as candidates and, despite all the dangers, the Loya jirgas were held and people were elected. Unfortunately, however, because the chance to truly develop Afghanistan was lost by the world, simultaneously, the warlords flourished and the Taliban became increasingly stronger and the elected members of parliament remained ineffectual.

Rashid discusses how the region continues to descend into chaos not only because the Taliban, like the warlords, started cultivating poppy (98% of the heroin sold in London comes from Afghanistan), but also because it still does not have a central authority. In Afghanistan, the war still goes on. In Pakistan, a large part of the Pashto-speaking area — FATA and Swat — are becoming Talibanised. Ahmed Rashid suggests that parts of the military in Pakistan feel that a “‘Talibanised belt’ in FATA would keep the pressure on Karzai to bend to Pakistani wishes.” If this is so — though unfortunately there is no proof to suggest what percentage of the decision-makers subscribe to this view — it would be a recipe for suicide for Pakistan. Furthermore, the evidence suggests that Islamic militants, driven by their beliefs, would impose their ideology and way of life on society without consulting their former supporters.

This brings one to the strengths and weaknesses of Ahmed Rashid’s book. The strengths are obvious. It is the first work on the policies and events which have made Afghanistan and Pakistan so volatile and unstable in the last few years. As news of girls’ schools and CD shops being bombed fill the pages of Pakistani newspapers, militants target the paramilitary and military forces and the writ of the state gradually loses its meaning in FATA and Swat — this book helps one understand why all this is happening. Rashid has actually lived and moved in this area, knows and understands it well and met a number of the actors, all of which lend his account credibility.

Nonetheless, actors may be untruthful or biased, and the secrecy which surrounds intelligence agencies makes it difficult to establish that everything Ahmed Rashid reports is absolutely accurate. It is not possible for any researcher to get his facts or analysis 100% right. That notwithstanding, there is no doubt that his major hypotheses are true.

All in all, Descent into Chaos is a very significant book which no social scientist can ignore.