In Memoriam: Khushwant Singh

By Sadia Dehlvi | People | Published 11 years ago

Over the last year, he had been repeatedly telling me, “I am ready to go…I want to go. Meri maghrib ki namaaz ka waqt aa gaya.”

I take solace in the fact that he lived and died exactly the way he wanted. As Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and other dignitaries placed flower wreaths over him, I thought of how Khushwant would have been amused and secretly delighted by all the media attention. Often, when commenting on the beautiful flowers on the table, Khushwant would tell me with childish delight, “Prime Minister ne bheje hain.”

I first met Khushwant nearly 30 years ago at a calligraphy exhibition. He walked up to me and asked, “Why are you so beautiful?” I laughed, replying, “Because I am a beautiful person.”

Khushwant promptly invited me to his house at seven the next evening. I went a bit late, got a dressing down from him, and learnt never to be late or early again! The visits to his home continued and soon I became a regular visitor, allowed to break the ‘only by appointment’ rule. He would say, “Breeze in whenever you like.”

We gossiped about everything from the morning headlines to why monkeys have red bottoms! A keen bird-watcher, every year he would predict when the showers were on their way. “I heard the monsoon bird,” he’d inform me.

We shared an incredible bond, a friendship that nurtured me intellectually and emotionally. He delighted in the fact that I flaunted our friendship to the media, once declaring in an interview, “the only man I love is Khushwant Singh.” He credited me with his notoriety, while I blamed him for mine, since he often mentioned me in his writings.

Khushwant’s evening ‘durbar’ became my window to the world of the rich, the famous and the absurd. All kinds of people would visit him, from world dignitaries, writers and artists, to poets and self-styled God-men. A people’s man, he enjoyed their stories and recounted most of them in his columns. A serious thinker, he did not understand why most people took themselves so seriously. Along with his scholarship, Khushwant brought malice, wit and humour to public life.

Khushwant often took me along to his dinner invitations, saying, “I want to show you off.” Sometimes he would order me to come along simply to save him from a boring host. A food connoisseur, he thought poorly of those who served bad food or poor quality whisky. He made excuses to avoid their invitations.

The only people Khushwant despised were those with communal biases. Carrying a soft corner in his heart for Muslims, he used to say “I cannot stand anyone who hurts a Muslim.” Over the years, he stopped meeting certain politicians and journalists on discovering their religious intolerance. He called them “poisonous snakes” and said he felt “unclean” with “fundos” of any religion.

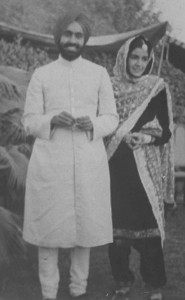

Singh with his wife, Kanwal Malik.

Of all his friendships, Khushwant’s most treasured was the one with the late Manzoor Qadir’s family in Lahore. The calligraphies and other symbols of Islam in his home remain a tribute to that cherished bond. A black and white picture of the two with their wives still stands on the living room table.

Khushwant remained my closest friend, the keeper of my secrets. His home was full of Delhi’s secrets, although he could not keep them for long: those close to him knew that if you wanted the world to know something, you just had to tell Khushwant it was a secret! Yet people confided in him, particularly women. Probably, because he listened to them with rapt attention, rarely judging their actions, lending his shoulder to cry on and trying to help in any way that he could. He could instantly turn into a friend, father and confidant, making everyone feel very special.

However, Khushwant would be baffled and amused when strangers shared details of their love affairs and private lives with him. Once an unmarried pregnant woman, unknown to Khushwant, arrived at his doorstep and sent him a note saying she was going to have a child in three days and wanted to deliver the baby in his home, under “his benign” presence!

Gentle, caring, genuine, honest, humble and a thorough gentleman, Khushwant never ever got drunk. He carefully cultivated his reputation of a “dirty old man,” the Sultan of sleaze, who loved good scotch and beautiful women. He thrived on controversy, loving abuse more than praise.

Khushwant never indulged in self-praise, and could not stand those who did. He would laugh and tell you how a senior newspaper editor had told him to his face that he had made bullshitting into an art. He often recalled how someone had sent him a letter addressed to “Khushwant Singh, Bastard, India.” He kept it, gleefully showing it off and proud that it reached him despite the envelope not having any address.

Some years ago, Khushwant told me about the man who called him up every day just to give him a gaali. The caller would abuse him and then hang up. This went on for several months, and when the calls stopped, Khushwant genuinely worried about the fate of the caller.

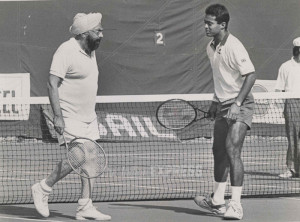

Singh with tennis player, Leander Paes, in 1994.

Fifteen summers ago, I bullied Khushwant into hosting a television show for Star TV, titled ‘Not a Nice Man to Know,’ where he interviewed women from various fields. Among them were Tehmina Durrani and Asma Jehangir, both of whom he enjoyed meeting. A major problem was that Khushwant did not wish to change his faded, stained shalwar kurtas for the show. “I have a reputation as India’s worst dressed man and I wish to keep it that way.” I pleaded that the television channel had objected to his shabbiness and that I wouldn’t get my money if he didn’t wear clean clothes. He finally agreed but continued to sulk every time we asked him to change his clothes. As a producer, it required persuasion to get him to accept the fee for anchoring the programme. He always said, “I don’t need the money. I have enough and don’t know what to do with it.”

In 1993, Khushwant dedicated his book, Not a Nice Man to Know, to me. It carries the dedication, “To Sadia Dehlvi — Who gave me more affection and notoriety than I deserve.” Two years ago, I dedicated my book, The Sufi Courtyard: Dargahs of Delhi, to Khushwant. I had thought of dedicating it to Khushwant and to the city of Delhi that we both love. When I told him this, he said, “Sirf mere liye…just write Khushwant and not the surname. This way it shows closeness.” I laughed and happily agreed. The dedication reads, “For my friend Khushwant, who has touched so many lives with his guidance, humility, generosity and compassion.”

Just the other evening, while sipping his one stiff peg of single malt whisky, Khushwant laughed, “I don’t waste time in prayer, I just read Ghalib.”

This article was originally published in Newsline’s April 2014 issue.

No more posts to load