Cultural Sovereignty and the Vibrant Nation

Pakistan’s citizens demand sovereignty. They feel that it is routinely violated by drone attacks as well as by insurgents who attack Pakistanis indiscriminately. The problem is they are not getting any of their demands met and will probably not for sometime in the future. Nor do the citizens have powerful enough instruments to push the state to become more efficient in the short-term. Pakistanis are slowly realising that neglected and decaying state institutions cannot be repaired overnight. And they are very angry, frustrated and depressed. So, even though Pakistan faces a multitude of problems from the economy to the insurgency, its citizenry’s predicament is that there is no way to channel their frustrations into policy changes.

Pakistan’s citizens demand sovereignty. They feel that it is routinely violated by drone attacks as well as by insurgents who attack Pakistanis indiscriminately. The problem is they are not getting any of their demands met and will probably not for sometime in the future. Nor do the citizens have powerful enough instruments to push the state to become more efficient in the short-term. Pakistanis are slowly realising that neglected and decaying state institutions cannot be repaired overnight. And they are very angry, frustrated and depressed. So, even though Pakistan faces a multitude of problems from the economy to the insurgency, its citizenry’s predicament is that there is no way to channel their frustrations into policy changes.

Sovereignty has two components. The first one is political: the nation state. However autonomy does not just extend to territory. It encompasses something more than the soil of a country, more than borders on a map. It is the drive to go about doing what you have always done. It is the drive to witness and dwell, come what difficulties may (death, destruction, poverty), in the richness of life — in what we call culture. Without vibrant culture there can be no vibrant nation.

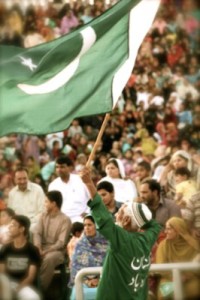

When a nation loses one component, the other also starts to crumble. However this can also work in reverse, strengthening one can also strengthen the other. Territorial sovereignty can strengthen culture, but in times of crisis it is culture that can strengthen the nation even if its physical boundaries are violated. Culture is physical, in the colours we adopt to wear and the songs we choose to sing. But it is also spiritual, based in religion, philosophy and ethics, which highlight the moral trajectory of a nation.

Most of us have grown up with some sense of Pakistani identity: what we call Pakistaniat. At the risk of defining it, I will simply say that an attack on Pakistan’s sovereignty has an effect on a person’s identity as a Pakistani. We want to prove ourselves to the world, but we are constrained by our homes, jobs and families. Cultural identity provides us with an opportunity to protect our cultural space individually, and this can pay positive dividends in a national sense.

The British realised this. Lord Macaulay, in his address to the British Parliament, on February 2, 1835, said, “I have travelled across the length and breadth of India and I have not seen one person who is a beggar, who is a thief. Such wealth I have seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation, which is her spiritual and cultural heritage… for if the Indians think all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self-esteem, their native culture and will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation.”

I am not calling for a rejection of Westernisation, English or the valuable progress Europe and North America have made in science. All culture must be able to shift and assimilate. But the people (especially the elite) must embrace local languages, values and thinkers. They must fashion new ideas from foundations that are familiar. Wear a Sindhi topi, learn to make a sajji in Balochistan, speak Pashto. Learn to read Urdu literature. Honour our cultural heritage (this does not mean growing beards or wearing niqabs), which dates back thousands of years. We must also widen our horizons when it comes to religious diversity. It is important to note that all great religions come from God, so there is no such thing as pre-Islamic, or at least there is nothing necessarily negative about pre-Islamic. We must move away from our apathy towards cultural monuments that are not Muslim in the classical sense. We must try and embrace the footprints of other religions and civilizations left in our country throughout history because it has left a mark on our subconscious.

When cultural sovereignty erodes, it is difficult for people to realise that it is being taken away from them. It slowly eats away at people’s way of life. Yet cultural sovereignty is an individual act and an individual choice — no power can take it from a people, if they choose otherwise. This is in stark contrast to political sovereignty, which while influenced by public opinion, in nascent democracies, is usually practiced by the ruling elite. The events in the past few weeks have shown us that the state cannot project hard power (diplomatically or militarily). It is time that the citizens of Pakistan assert cultural sovereignty. In time, we can perhaps take back our political sovereignty as well.