A Piece of Art History

As the older neighbourhoods of Karachi keep pace with change in this fast growing city, old blocks are routinely being transformed with houses and old-style apartments making space for towering commercial projects and office blocks.

One impending casualty in this commercial race is a serene apartment block nestled in a PECHS street. There are four flats here, the residents of which have been renting this space for the last 50 years at least. What few may know is that one of these flats was occupied by Pakistan’s foremost sculptor, the late Shahid Sajjad and his family. He not only lived here but also had his workshop on the premises housed in a shed within the boundary walls.

Almost all of his most iconic works were carved or moulded here. His children grew up and moved away, Shahid Sajjad himself passed away. Today the flat is occupied by his wife, Salmana Shahid, while the now quiet workshop houses a collection of the late sculptor’s work, his tools and a myriad memories.

” I made the mistake only once of cleaning out the studio,” reminisces Salmana Shahid. “The reaction was so extreme I never did it again. He said you are most welcome to come in, spend time here but don’t move things around.” In fact, till today, some things are placed just where he left them.

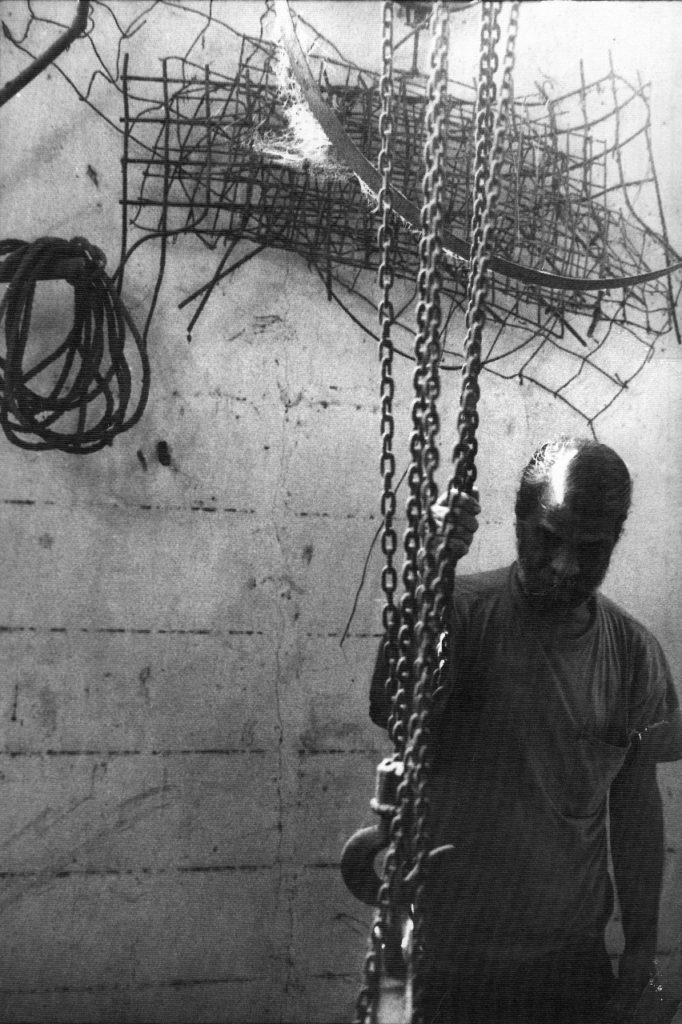

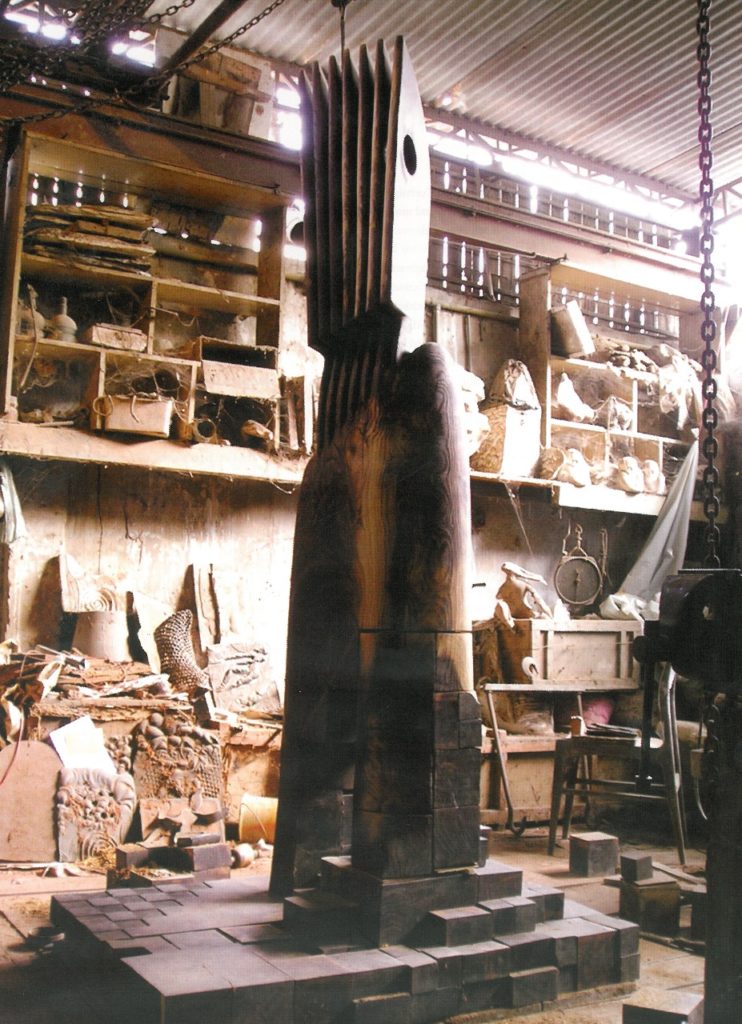

The workshop is a piece of Pakistan’s art history. As Shahid Sajjad moved from wood carving to bronze casting and back to wood carving , the workshop saw tools added or subtracted, new techniques explored and fantastic creations come into existence. From the towering to the smallest figure, each one was a labour of love.

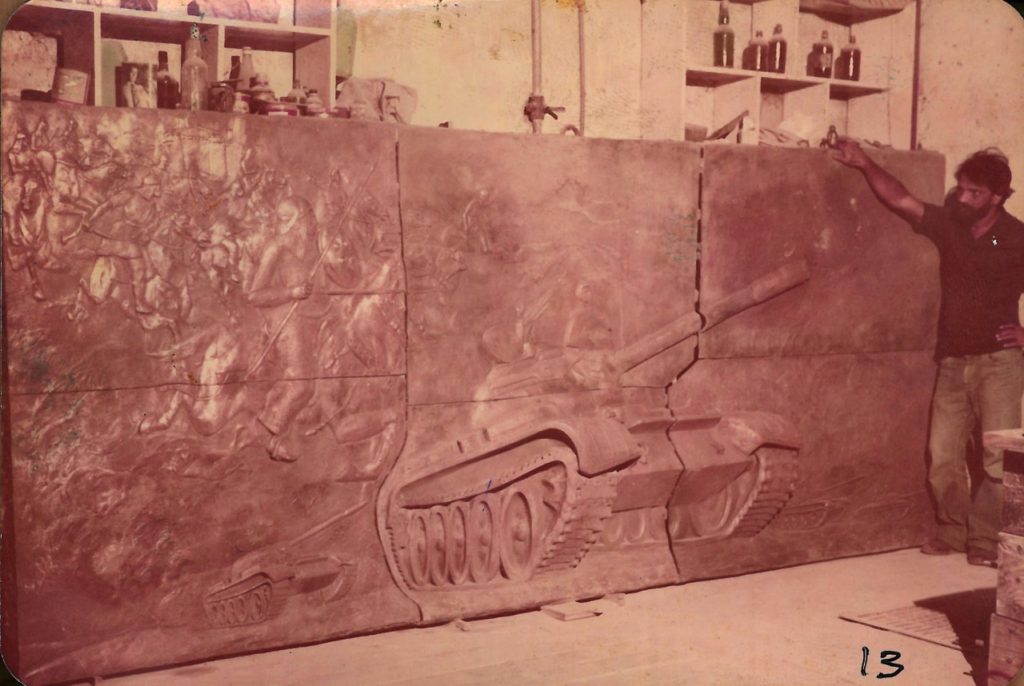

The Rangamati series of wooden figures was finished here. The iconic Nowshera Bronze relief that was commissioned by the Pakistan Army was cast here. This mammoth relief weighed one ton when it was finished and was cast in six separate pieces, often at the risk of life and limb. In fact, the then president, General Ziaul Haq, came to see the finished work at the sculptor’s home. No single artist had created a work of this scale before in Pakistan.

For bronze casting Shahid Sajjad worked in the Lost Wax Method. He was the only practitioner of this ancient craft in Pakistan and with his demise the secrets of his trade have died with him – in this country at least. In his workshop, lie the last tools and implements of this craft.

He learnt the technique from a Japanese sculptor, Kato San, but not after hours of apprenticeship. He spent one session observing him and then practised on his own, following verbal guidance and after much trial and error. After he cast the Nowshera Bronze, Kato San was moved to say that “the student has now become the master.”

As a child, I recall spending a day at the workshop watching the bronze-casting process and feeling like something very momentous, magical and slightly dangerous was taking place. It was a privilege to be allowed into the artist’s inner sanctum but Shahid Sajjad was always comfortable around children.

The stillness of the workshop must still hum sometimes with the throb of the hammer and anvil while the tools and tables bear the imprint of the artist’s loving hand. “The wood carving tools were collected by him and brought from Japan, ” says Salmana Shahid. “These tools are quite unique.” In the last years of his life, the sculptor struggled with ill health. But when feeling a little stronger, he worked on carving beds for his sons – for Shahid Sajjad was as much a labourer as an artist. For him there was no distinction between art and craft. I remember him talking about his fascination with the mechanics of everyday objects and how they were made. The beds were the last thing he worked on before his demise.

Shahid Sajjad did little in his lifetime to further his own material interest. He was a true bohemian who shunned commercialism and lived on his own terms. So what should be done to preserve and pass on the invaluable legacy of this artist? In a country starved of cultural archives and resources, the birthing place of Shahid Sajjads’s oeuvre must not be lost to another ubiquitous office block.

One solution is to place all his works, finished and unfinished, along with his tools, photos and other belongings in a small museum dedicated to Shahid Sajjad’s memory. ” It will not be his workshop but we could put up the pictures of him working there. There would be some record. And it should be open to all,” says Salmana Shahid. Such a space would not only do justice to Shahid Sajjad’s genius but enrich the city and its generations.

Zahra Chughtai has worked and written for Pakistan's leading publications including Newsline, the Herald and Dawn. She continues to write freelance.