Partners With Purpose

By Kunwar Khuldune Shahid | Newsbeat National | Published 9 years ago

Pakistan’s year on the diplomatic front ended with the familiar, but now increasingly infrequent US call to ‘do more.’ According to credible sources, US officials met with Pakistani government representatives in London, to discuss Tashfeen Malik’s links with Abdul Aziz’s Lal Masjid. Tashfeen was the female shooter in December’s San Bernardino attack, and insiders confirm that evidence of Tashfeen’s affiliation with Lal Masjid was provided to the Pakistani contingent. It is now clear — Pakistan’s reiterations of indiscriminately fighting terror hinge in large part around the future of Abdul Aziz, and the militant women’s wing run by his wife, Umme Hassan.

That aside, it was a relatively quiet year for US-Pakistan relations, with America, post its nuclear deal with India, increasingly cosying up to our neighbour. Little surprise then, that the back-to-back visits of PM Sharif and General Sharif to the US were centred around Pakistan’s nuclear programme, which has been forcing India to up the ante on its missile production as part of the much-touted ‘Cold Start’ doctrine.

The void left by the US’ pivot eastwards in Asia, has, however, been more than filled by China, with the $46 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), providing impetus to Pakistan in the energy, economy and security realms. The multi-pronged CPEC routes run through the entire length and breadth of Pakistan, making any form of militancy detrimental to the project’s future. The Taliban, Baloch insurgents and Uighur militants — who were alleged to have been trained in the north-west — were all deemed antagonistic to the future of the CPEC. And so, coinciding with Sino-Pak diplomatic toing and froing, and signatures on MoUs, Zarb-e-Azb, launched in 2014, was the logical corollary of Chinese apprehensions with regards to Islamist militancy in Pakistan.

With Russia recently renewing its military alliance with Pakistan, and the resumption of arms sales to Islamabad, another global power has been added to a nascent axis. A ‘landmark’ Russia-Pakistan defence deal, which included the sale of four Mi-35 ‘Hind E’ attack helicopters, was signed in August, two months after General Raheel Sharif’s visit to Moscow, where the draft contract for the delivery of the combat helicopters was finalised. Two months after that, in October, Pakistan and Russia agreed to lay a $2.5 billion pipeline to carry imported liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Karachi to Lahore.

Even so, while Islamabad’s growing diplomatic proximity with Moscow, amid increasingly flourishing New Delhi-Washington ties, perpendicularly reshuffles the Cold War alliances, Pakistan drawing closer to Russia will irk another traditional ally: Saudi Arabia.

Russia’s unflinching support for the Assad regime in Syria obviously brings Islamabad’s alliance with Moscow at odds with Saudi interests in the Middle East. The fiasco over Pakistan’s participation in the Saudi-led 34-country ‘Islamic’ military alliance to fight terrorism, which conspicuously excludes the so-called Shia Crescent states, including Iran and Iraq, was possibly fuelled by Islamabad’s budding alliance with Moscow.

While Pakistan eventually “voluntarily” agreed to be a part of the Saudi-led military alliance, the year was marred by confusion over Islamabad joining Riyadh in the latter’s Middle Eastern military expeditions. Nawaz Sharif might have reassured the Saudi royalty — his saviours during his political exile in the Musharraf years — of Pakistani support in Operation Decisive Storm, the anti-Houthi operation in Yemen, but the National Assembly decision opposing Islamabad’s participation in the GCC alliance, was a significant moment in Saudi-Pakistan ties. There is a growing sentiment in Pakistan against unconditional support for Saudi Arabia, especially with Iran offering a lucrative alternative for Pakistan’s energy and commercial needs.

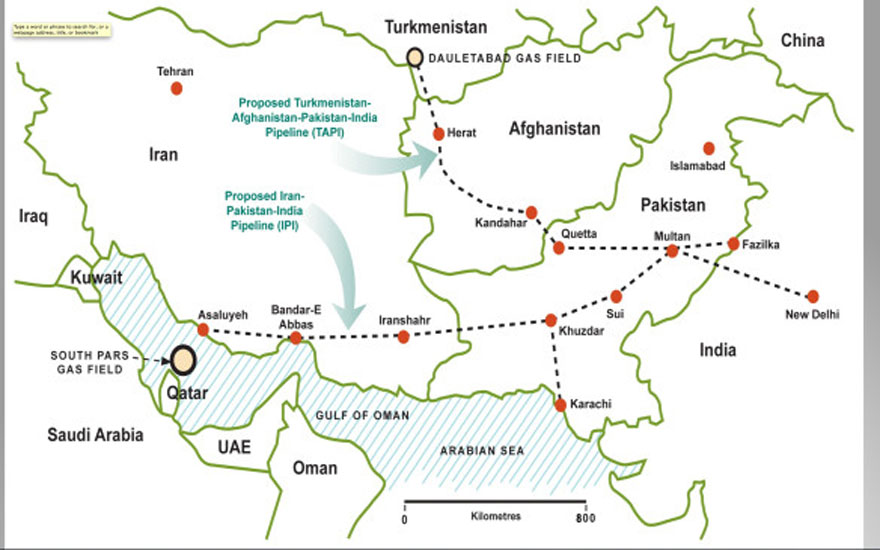

In addition to avoiding being party to any sectarian Saudi-led alliance, balancing diplomatic ties between Saudi Arabia and Iran has become even more crucial following the Washington-Tehran nuclear deal. In September, the Minister for Petroleum and Natural Resources, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi, vowed to complete the Iran-Pakistan (IP) pipeline by 2017, carrying 310 billion cubic feet of natural gas from Iran to Pakistan annually.

In addition to the growing violence against the Shia community, which has killed over 4,000 people since 2007, a growing cause for animosity from Iran has been cross-border terrorism from Al-Qaeda affiliated Islamist militant organisations like Jaishul Adl in Balochistan. It is the same concern that China has professed with regards to Uighur militants, India to Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT)-affiliated jihadists and Afghanistan regarding the Afghan Taliban.

The failure of the Taliban-Afghan government talks in Murree, following the announcement of Mullah Omar’s death and the change in the Afghan Taliban leadership exacerbated Islamabad-Kabul hostility in a year wherein President Ashraf Ghani called out Pakistan on multiple occasions. The most noteworthy of these was a attack in Kabul in August which killed over 50. Later, in an interview to BBC, the Afghan president said that Pakistan and Afghanistan “weren’t brothers,” but two states with ties dictated by respective self-interests. As is evident, Pakistan’s diplomatic ties with neighbouring countries depend on the eradication of safe havens for Islamist terror groups.

This is obviously true for Indo-Pak ties as well, which remained typically acrimonious for most of the year. Among the many spark points was the Islamabad High Court’s (IHC) inaction over LeT leader Zaki-ur-Rehman Lakhvi

with regards to the Mumbai attack case. Lakhvi also refused to send his voice samples to India for investigation, with China blocking India’s move regarding Lakhvi in the UN. Also, in August, the Indian media was brimming over with reports over a “Faisalabad-based” militant infiltrating the border and Indian security agencies arresting him, in front of whom he “spilled the beans.”

After a year of diplomatic mud-slinging and LoC infiltrations from both sides of the border, Indo-Pak ties ended on some semblance of positivity, with the Nawaz-Modi meet-up during COP-21 in Paris, Indian Minister of External Affairs Sushma Swaraj’s visit to Pakistan during the Heart of Asia Conference — which also helped build a few bridges between Islamabad and Kabul — and the ostensibly unscheduled “private” visit by Narendra Modi to Nawaz Sharif in Lahore, on the former’s return from Kabul to Delhi. The friendly diversion and warm embraces of the two Prime Ministers were all-the-more baffling given Modi’s reported anti-Pakistan harangue in Afghanistan. Clearly, a lot more work needs to be done to actually even begin a dialogue aimed at addressing the real issues that plague relations between the two nations.

The announcement of work on the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline, where PM Nawaz inaugurated the project along with President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov of Turkmenistan, President Ghani, and Vice President Mohammad Hamid Ansari of India in the Karakum desert, is one project which could provide diplomatic impetus to the region. Should both TAPI and IP materialise and link with CPEC, an energy-sharing grid could connect this bloc of countries from South (east) Asia with Central Asia and the Middle East — involving Russia as well — and overcome bilateral and multilateral paranoia and insecurities. Economic interests would be interlinked throughout the region, with all states becoming stakeholders in each individual country’s security, leading to the much-needed realisation of collective security in the volatile region.

It’s safe to say that such an idea sounds much less implausible at the end of 2015 than it was at the year’s start. But due to Pakistan’s strategic location as the hinge of such a symbiotic network, and the hub of instability in the recent past, Islamabad will have to continue to do a lot more on the foreign policy front going into 2016.

This article was originally published in Newsline’s Annual 2016 issue.

Kunwar Khuldune Shahid is a journalist and writer based in Lahore.

No more posts to load