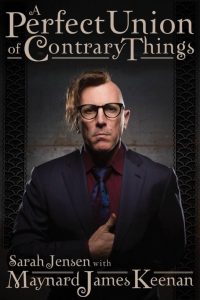

Book Review: A Perfect Union of Contrary Things

A Perfect Union of Contrary Things by Maynard James Keenan and Sarah Jensen (Backbeat Books, US, 2016)

A Perfect Union of Contrary Things by Maynard James Keenan and Sarah Jensen (Backbeat Books, US, 2016)

It is fitting that the memoir of a frontman of, arguably, the most cutting-edge outfits in contemporary music (Tool, A Perfect Circle, Puscifer) should defy the conventions of rock-stardom. Mapping an inspirational journey of a struggling artist, this autobiography appeals to those fans that are interested in knowing more about Maynard James Keenan the spiritual seeker, philosopher, winemaker, soldier, athlete and nature-lover.

Lacking in the clichés and wild orgiastic escapades that fill most rock memoirs, the underlying theme that binds A Perfect Union of Contrary Things (Backbeat Books, 2016) is its veneration of nature and the sublime; a profound appreciation of the outdoors, of which we are provided a vivid flavour thanks to the collective literary abilities of Keenan and his longtime friend Sarah Jensen, who co-authored the memoir.

It was by being in close contact with nature — be it cultivating a vineyard, cross-country hikes or an aviary — that Maynard found the grounding he had been searching for. Throughout his life, this contact formed the basis, a reference point of sorts, to his epochs.

An intricate little sketch at the top of each chapter, of a finch hovering above a vine, serves as a constant reminder to the reader that Maynard’s passion for winemaking and pet birds outweighs his endeavours as a musician.

The humility and subtlety of the narrator’s voice is refreshing as the ego is traded in for sharp observations of meaningful day-to-day occurrences that resonate with the reader on a personal level. Reflecting on the sense of liberation he felt upon being a complete stranger in his new school, Keenan explains, “I wasn’t subject to the hierarchy that had already been established with these kids who grew up together and who knew each other’s faults and flaws… I wasn’t pigeon-holed into the established social order.”

Embarrassing moments of the kind that most memoirs would prefer to leave out, are frankly recollected with a touch of wit, such as the time when Maynard held an open house on graduation day for friends and visiting relatives, to which he recalls “Not a single f***ing person came.” Or the time he was ignored by his former high school classmates upon his return to his hometown (Scottville, Michigan) after a stint in the army.

The mention of such rejections — including the selection of Zach de la Rocha over Keenan as vocalist of Rage Against the Machine in 1991 — give Maynard’s persona an accessible, human dimension and simultaneously serve to encourage readers to face their own psychological hurdles. As Maynard rightly points out, “The hurdle is you.”

The wisdom dispensed by Keenan echoes the teachings of the most unexpected mentors and father figures, including one intellectual Reverend of the Church of the Brethren, a teacher and cross-country-running coach, his coach at the US Military Academy Preparatory School at Fort Monmouth who encouraged him to “think beyond the obvious” and his jiu-jitsu instructor — brother of UFC founder Royce Gracie — through whom Maynard learned to access the psychological through the physical: “Instead of trying to push back, I learnt to step outside the situation.”

Ever since their years at the Kendall College of Art and Design, Maynard and his friends Kjiirt and Ramiro closely applied Carl Jung’s theory of synchronicity to what they believed were meaningful coincidences in their lives. For instance, Maynard was to discover that a foreboding dream he had about his friend, comedian Bill Hicks, was more than a mere coincidence. Similarly, his recurring dream of flying — the bird lover that he was — over a semi-arid rocky terrain was a precursor to his move to that very location, which turned out to be in Jerome, Arizona. On a visit to a vineyard in Italy while on tour in 2000, Maynard was quick to connect the topography of the region to that of his new home in the Verde Valley; “I just knew this is what it felt like when I stood outside my house.”

Keenan found solace in his interpretation of comedian Bill Hicks’ philosophy which encouraged him to “embrace the journey” by shaking off social pressures, knowing that life was “just a ride.” However, this proved difficult to achieve in Los Angeles where, bogged down by his celebrity persona, Maynard explains, “I felt like so much was polluting my ability to remember that it was all just a ride.”

Earlier, upon graduating from high school, Maynard had joined the military primarily out of financial necessity, whereby service in the army would make him eligible for tuition money. True to character, instead of rebelling in the army, he strove to perfect what was expected of him whilst at the same time maintaining his integrity as an artist. The following excerpt on his time in the military provides an insight into the inner workings of the artist soldier:

“And with the artist’s instinctive need to rearrange life’s tidy boundaries, he grew impatient with the cosseted life of comfortable bus rides to cross country invitationals and the warm, carpeted room at the end of the day. The others unquestioningly accepted their protected existence, an existence uncomplicated by the messy disorder of half-learned guitar riffs, in-progress poems, and paint-splattered studio floors. His combat training soon led him to make the profound observation that, as early as 1983, the US army was being prepared for desert warfare.”

The memoir also provides a detailed account of the rise of Tool, A Perfect Circle and Puscifer. Of how it took losing everything Maynard had — his job, his apartment, his woman, his car and his dog — in a town where he was a complete stranger, for him to channel from his gut the primal screams that would take Tool to unprecedented heights.

Like the healing quality of Keenan’s lyrics, the memoirs too create a sense of hope against all odds and can be a useful self-help guide for aspiring artists.

The writer is a staffer at Newsline Magazine. His website is at: www.alibhutto.com