The Venice Biennale: Of Borders and Bodies

By Niilofur Farrukh | Art Line | Published 7 years ago

Themes of waves of immigrants, refugees and displacement have become central to art at a time when huge movements of people have raised crucial questions on borders, resources and lives. These concerns were examined in powerful projects on display at the 57th Venice Biennale (May 13- November 26), to illustrate the effects of social, political and historical conditions on human experience.

Georgian artist Vahjiko Chachkiani exhibited his installation at the Pavilion of Georgia with his work, ‘ A Living Dog in the Midst of Dead Lions.’ This is a reconstructed wooden hut from the countryside in Georgia, reassembled to actual scale. Its bleached wood and rundown condition is meant to bring the reality of the slowly emptying mining towns into the ‘Arsanale’ indoor space. The eerie yellow light of the interior reveals a persistent gentle rain falling inside the rooms, as if calling upon nature to reclaim the meagre belongings through mould and decay. According to the artist, it deals with the “inner lives of people attacked by historical or social circumstances. Possibly one could say that I am dealing with ‘interiors’ in the many layered sense of the word : the interior life, the hinterland and the heartland, the interior.”

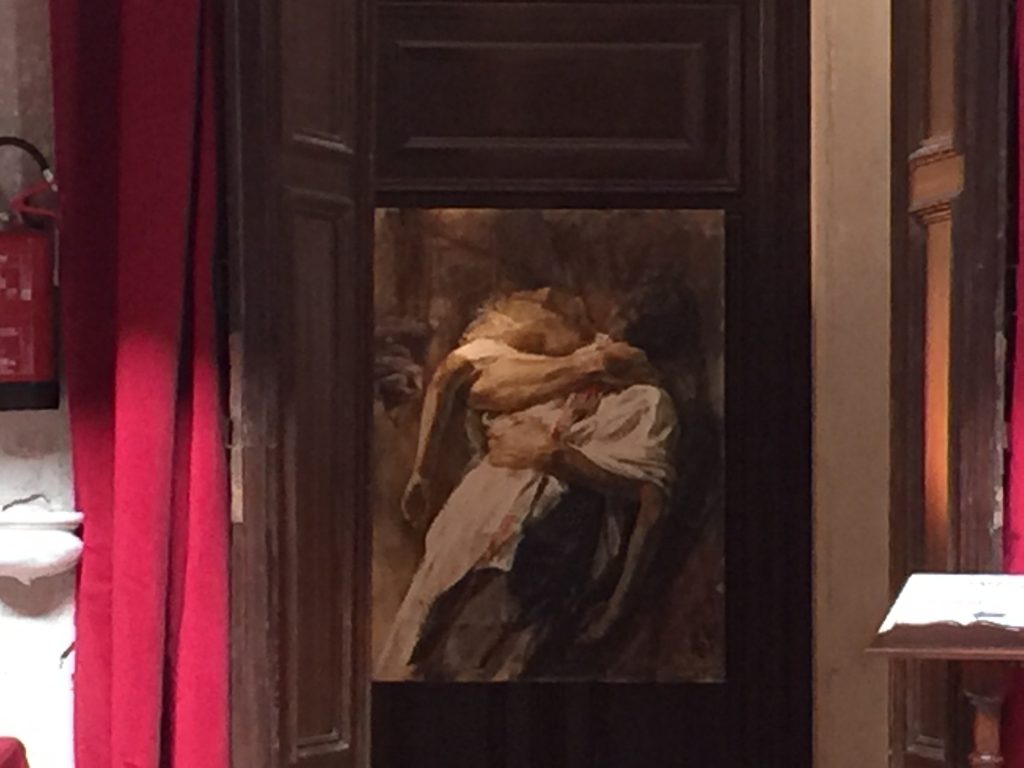

Safet Zec: Exodus -One

In 2015 alone, according to the UNHCR, a population of 65.3 million people were displaced from their homes by conflict and persecution — i.e one person in 113. Chachkiani’s empty house installation, complete with furniture etc., connotes the life left behind by war, famine, persecution, fear and economic hardship; a time when ‘displacement’ is doing what famine did in the past centuries — driving people out, and altering the emotional DNA on a scale never seen before.

Bosnian artist Safet Zec has chosen to hang his painting series ‘Exodus’ in the Church of Santa Maria Della Pieta. Here biblical narratives become the new lens to examine the plight of 21st century refugees. The echo of the pain and persecution, that led to the ‘Passion of Christ,’ seemed to reverberate through the church with a new meaning. The light framing the painting with the dismembered torso of Christ, that replaced the crucifix, in the central nave, seems to draw the eye into the deep space before moving to canvases that hang along the walls with life-sized huddled refugees, resting before they face the unknown. Only when turning to leave, does one see the nearly 30-feet-long canvas of a beach with a little body of a boy, an image that shook the conscience of the world some months ago.

‘The Absence of Paths,’ staged at the Tunisian Pavilion (the first time since 1958), is an art performance that invites people to join a movement that challenges border regulations and focuses on migration and freedom of movement. Here, one can register as a migrant with ‘Origin: Unknown,’ ‘Destination: Unknown,’ or ‘Status: Migrant,’ and get a Universal Travel Document that looks like an official visa. In kiosks spread all over Venice for the duration of the Venice Biennale , people can register and call for a world with ‘open borders’ to be a citizen of no-where and every-where. According to them, this gentle individual protest is designed to evoke the possibility of flexibility that recalls the first step our ancestors took 70, 000 years ago, when they left the African continent to populate the world.

Absence of Paths: Tunisian Pavilion

At Correr Museum on San Marco, Iranian artist and filmmaker, Shireen Neshat’s video confronts the fragile emotional state of the migrant. Her protagonist, a woman, treks through stony deserts, and wades through slush and silt, only to feel trapped within paranoia. The film locks the audience into a feeling of never-ending hopelessness born out of the frustration of never being whole again. A deprivation of someone who cannot fully belong or fully return to his /her origin after a transformation in the new land that prevents integration back home. A conflict that could well be biographical as the artist, self-exiled herself many decades ago, and now her art has turned this exile into a state-sanctioned one blocking a return.

These works bring into question the vital question of precious histories of belonging through language, memories and physical bonds that displacement shatters to allow survival through integration. When inner disharmonies metastasize into trauma, it becomes the tragedy we see around us. These works at the Venice Biennale are both about today and what can happen tomorrow — on a much larger scale.