Vale of Uncertainty

By Owais Tohid | News & Politics | Published 21 years ago

“Learn Quran,” reads the board posted at the entrance of a double-storied house in a working-class neighborhood outside Islamabad. A few young, well-built boys hover around, apparently guarding the building. They are unarmed. Inside, a staircase leads to a large basement, where young and middle-aged men with beards of different sizes are resting, most lying supine on the floor. The walls are plastered with posters depicting militants fighting Indian security forces in the Kashmir valley.

“Learn Quran,” reads the board posted at the entrance of a double-storied house in a working-class neighborhood outside Islamabad. A few young, well-built boys hover around, apparently guarding the building. They are unarmed. Inside, a staircase leads to a large basement, where young and middle-aged men with beards of different sizes are resting, most lying supine on the floor. The walls are plastered with posters depicting militants fighting Indian security forces in the Kashmir valley.

This is the hangout of local Kashmiri militants, ostensibly inactive in the wake of Islamabad’s changing Kashmir policy. New efforts by the administration to rein in militants from Pakistan crossing the Line of Control, into Indian-occupied Kashmir, has apparently had the desired effect — at least to some degree.

“This has been my life,” says a tall, fair-complexioned Kashmiri man, Javed Meer, pointing to a poster on the wall in which a mujahid is portrayed targeting an Indian tank. “I have grown up with it. My life is to wage jihad and liberate my motherland from the cruel Indians. I have sacrificed everything. How can I turn my back on my own people, my land and the aim of my life?” says the 26-year-old Javed. “Washington can put pressure on Islamabad, but not on us. It can slow down the militancy, but cannot stop it. We are Kashmiris and nobody can stop us from crossing the LoC. It will be a betrayal,” he adds. A pause, and then, after that impassioned speech, some uncertainty. “Do you think our struggle will end due to the increasing pressure?” asks Javed.

Like him, around 5,000 Kashmiri militants in Pakistan are left disillusioned and embittered after Islamabad’s visible distancing from the jihadis. After his recent visit to Pakistan, US Deputy Secretary of State Richard Armitage said President Pervez Musharraf gave him “assurances that there was nothing happening” across the LoC and that guerrilla camps either no longer existed or “would be gone tomorrow.” Mr. Armitage’s visit to the two countries was an effort to make the nuclear-armed rivals — Pakistan and India — understand how imperative friendship between them is for the stability of all of South Asia.

New Delhi and Islamabad have made substantial headway in this direction, with a resumption of High Commissioner level diplomatic ties — virtually severed more than a year ago — Islamabad’s release of Indian prisoners and both sides agreeing to restore rail and air links (although no time frame has been announced for the restoration). Most significantly, there have been signals — albeit confusing ones sometimes — of a willingness to talk on all issues, including Kashmir. However, New Delhi has continued to maintain that enduring peace cannot be established until Islamabad stops the militants from infiltrating into Kashmir, and the international community concurs with this view as evinced by its continuing pressure on Islamabad in this regard. The US decision last month to declare the two largest Kashmiri groups, Hizbul Mujahideen, with 4,000 fighters, and Jamiat-ul Mujahideen with a force of 2,000 trained guerillas, as terrorist groups, is seen as a tacit declaration by the US that the Kashmiri militant campaign is a “terrorist,” movement.

The relentless pressure on the Pakistani government seems to have engendered ‘positive’ results. President Musharraf himself now seems to be coming down hard against militancy. This worries Kashmiri militants like Javed Meer who believe that if General Musharraf continues his policies, some small groups may fall by the wayside, leaving thousands of jihadis with no sense of direction. Some Kashmiri fighters admit that due to the massive deployment of Indian and Pakistani troops along the LoC and the new resolve of the Pakistani forces, cross-border traffic by militants across the LoC has already decreased. They contend that if the “moral” support hitherto lent by Pakistan dries up, the Kashmiri mujahideen’s supply line will be virtually cut off, which will deal a serious blow to the ‘jihad’ in Indian-administered Kashmir.

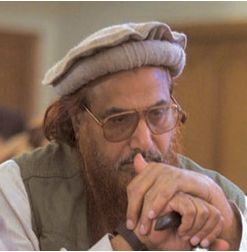

“If the militancy ends, what will bring India to the negotiating table? There is no other tactic. India will have a free hand to kill and further suppress Muslims in the valley,” says Ghulamullah Kiyani, known as the intellectual voice of Kashmir’s militant groups. “We are not against talks, but with India our guns should not be silent.”

He continues, “If Islamabad succumbs to the pressure, it will be a blow to the Kashmiri freedom struggle. What will the future of the Kashmiri mujahideen, who have pledged their very lifeblood to the cause, be?”

Pakistan’s position aside, the alleged corruption among some mujahideen commanders and infighting between the rival factions of the Hizb has triggered fears that the movement may be substantially eroded. The assassination of Hizb chief operational commander, Majeed Dar, in March, sparked clashes within the group, resulting in at least two deaths of fighters in Muzaffarabad and Rawalpindi. Last month, Dar’s men accused Hizb chief Syed Salahuddin of masterminding the murder, a charge vehemently denied by Salahuddin’s supporters. Thereafter, according to reliable sources, Dar’s men took control of the Hizb office being run by Salahuddin’s men in Rawalpindi. Gunfire was reportedly exchanged by the rival factions, and grenades were hurled. Dar’s men allegedly pocketed a large amount of Pakistani currency from the office before eventually vacating the premises.

Such events further impact the already shaky movement. A change is already visible in the mujahideen’s ranks. Many have started maintaining a low profile, others have gone underground, yet others have joined the mainstream.

“I have killed Indian troops. I have fought against them in Srinagar, Sopore and Baramulla. I was known as ‘Mr Grenade’ because of my expertise, with these firearms. But now I drive a cab the whole day and earn 200 rupees, and in the evenings I spend time with my old friends from the battlefield,” says 29-year-old Mohammad Iqbal, a Hizb activist. However, he is not entirely reconciled to his new existence. “I feel betrayed. I feel I have been caught in the crossfire,” he says. “My younger brother is missing. My nephew was murdered by Indian security forces. Now we are being forced to be pragmatic.”

Hizbul Mujahideen chief and chairman of the Muttahida Jihad Council, an alliance of Kashmiri militant groups, Syed Salahuddin clearly realises that the ‘jihad’ is running into trouble, and keeps exhorting the mujahideen cadres to keep their spirits up. “The mujahids should not lose heart. Militancy will be strengthened by the grace of Allah,” he says (see box). How far his pleas will carry, only time and the developments in the Indo-Pak detente will determine.

Hizbul Mujahideen chief and chairman of the Muttahida Jihad Council, an alliance of Kashmiri militant groups, Syed Salahuddin clearly realises that the ‘jihad’ is running into trouble, and keeps exhorting the mujahideen cadres to keep their spirits up. “The mujahids should not lose heart. Militancy will be strengthened by the grace of Allah,” he says (see box). How far his pleas will carry, only time and the developments in the Indo-Pak detente will determine.

Although Pakistan has always supported the independence struggle in Kashmir, jihadi culture has been promoted in the country in an organised manner for the last two decades. During the Afghan War against the Soviets in the ’80s, Muslim militant groups from across the Muslim world were given world sanction to wage jihad against the occupiers. With state approval, Pakistan became the base of this operation. After the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Afghanistan, the jihadis found themselves at a loose end. However, another “cause” soon appeared: the freedom struggle in Indian-administered Kashmir. Many of the militants who headed in that direction were trained in camps of the former commander of the Hizbe-Islami, Gulbuddin Hikmatyar, in Khost. Once again, the road to Kashmir was via Pakistan and as the mujahids made their way to the disputed region, they drew in a large number of Pakistani recruits.

Not surprisingly then, until recently, every village and town in Pakistan was awash with graffiti glorifying holy war. Pakistan-based jihadi groups involved in the fighting in Kashmir, such as the Jaish Mohammad and Lashkar-e-Taiba, glorified the “martyrdom” of local boys and constructed monuments in their memory in villages and towns, in the process recruiting young boys and collecting donations for the cause. The ranks of the indigenous Kashmiri fighters thus swelled manifold. At the same time, hordes of educated Indian-Kashmiri youths involved in the struggle would cross the LoC into Pakistan when ever the situation became too hot to handle. According to sources around 25,000 Kashmiri fighters belonging to different groups, routinely crossed the line of control into Pakistan over the past 13-14 years, with local authorities benevolently looking the other way. Kashmiri groups, in fact, even established their media centres and arranged visits for international and local media persons to their training camps in Muzaffarabad and other towns in Azad Kashmir. Furthermore, they conducted training programmes for new recruits and special commando training ones for experienced fighters. Boys were trained to handle Kalashnikov rifles, rocket launchers, hand grenades and other explosives for warriors,’ and they would display the heavy ammunition they had been given publicly. The Kashmiri groups operated from the state-of-the-art offices they had set up, which had several rooms that served as guest rooms. Each group had a hierarchy based on the pattern of a regular army, with powerful supreme commanders, followed by commanders, all of whom drove around in convoys of four-wheel drive vehicles, flanked by armed bodyguards. And all this in full view — if not with the financial support of — sections of the Pakistani establishment which has always viewed Kashmir a pivot in Pakistan’s foreign policy.

While Islamabad has always termed its support as “moral and diplomatic,” some events have revealed the erroneousness of this claim all too graphically. For example, when Kashmiri guerillas fought alongside Pakistani troops in the frontlines during the Kargil conflict against Indian forces in 1999, the nexus became eminently visible.

Things only changed vis-a-vis Pakistan’s stance towards the Kashmiri movement after Pakistan joined America’s war on terror. General Musharraf launched a campaign to marginalise militant groups in Pakistan and banned five groups, including two Pakistani Kashmiri groups, the Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammad, after they were accused by New Delhi of attacking the Indian parliament building on December 13, 2001. Following the ban, the parties’ leaders, Maulana Masood Azhar and Hafiz Saeed, were detained. Their offices were dismantled, their activities closely monitored, donation boxes vanished from public places. However, soon thereafter, these groups re-emerged with new names. The Jaish renamed itself Khadimoon-ul Islam (Servants of Islam), and Lashkar continues to operate under its new banner of Jamaat-ud Daawa.

After a short incarceration, the two party chiefs were released. Until recently, Lashkar Chief Hafiz Saeed was delivering speeches in public meetings calling for jihad. And despite its leader’s confinement, the party has managed to remain a potent, organised force. According to one estimate, it collected over a million hides of sacrificial animals on Eid-ul Azha, a powerful indicator of the group’s ability to mobilise support.

Other banned groups — most of which drew their members from non-Kashmiri militants — have taken cues from the Jaish and Lashkar. The Harkat-ul Mujahideen, led by Maulana Fazal-ur Rehman Khalil, which was banned by the US State Department in 1998 and had its assets frozen, has resurfaced as the Jamiat-ul Ansar.

No ban has been placed on Kashmiri militant groups by Islamabad, despite the ban placed on Hizbul Mujahideen and Jamiatul Mujahideen by the US. “The government has not banned the Hizbul Mujahideen, as it has no presence in Pakistan,” says Federal Interior Minister, Faisal Saleh Hayat. “The Hizb is a Kashmir-based organisation and the authority to ban it lies with the Azad Kashmir government.” He adds, “However, Pakistan’s policy is crystal clear. The government will not allow any individual or a group of organisations to use its territory for launching terrorist attacks on a third country.”

But while Islamabad’s recent policy to root out extremist elements from the country is being hailed by the international community, Kashmir remains a sensitive issue for the defence establishment and for many Pakistanis.

“I do not think that the Kashmir policy can change overnight. It cannot be wished away if Washington or New Delhi or Islamabad say so. The best future lies in a meaningful dialogue between Pakistan and India,” says analyst Nasim Zehra. “It will depend how sincere New Delhi is and how willing it is to resolve the Kashmir issue according to the wishes of the people of Kashmir.”

General Musharraf knows how tricky the situation is. Extremist groups have long been operating with impunity in the country and have made significant inroads into sections of Pakistani society. Their political support comes from a strong political alliance of religious parties, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal, which is ruling the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and is a major coalition partner in Balochistan. Members of this alliance, are not just ideologically aligned to the jihad in Kashmir, some have also directly participated in it. MNA Sabir Awan and Maulana Usman, a provincial legislator from the NWFP, both of whom belong to the Jamaat-e-Islami, participated in the jihad in Kashmir in the early ’90s.

The parties constituting the MMA see General Musharraf as a puppet of America and the western powers. Thus, he has to deal with both internal and external pressure, and neither side is willing to give an inch.

Meanwhile, Kashmiri commanders say they are adopting a wait-and-see policy. With New Delhi and Islamabad at the negotiating table and Washington pushing them along, the future of the Kashmiri militants hange in the balance.

Says a founding member of the Kashmiri movement, “After 9/11 the continuation of militant campaigns across the globe is not easy. Take the LTTE in Sri Lanka which has had to change its policy. It all depends on New Delhi; if it shows flexibility during the negotiations, then the Kashmiri militants will have to fall in line and lay down their guns. If not, the militants will gain a new lifeline. And guns will once again rule the Kashmir valley.”