#UsToo

By Fouzia Saeed | Viewpoint | Published 6 years ago

Fouzia Saeed is Executive Director at Lok Virsa — the Pakistan National Institute for Folk and Traditional Heritage. She has authored three books: Taboo! The Hidden Culture of a Red Light Area, Working With Sharks and Folk Heritage of Pakistan.

Fouzia Saeed is Executive Director at Lok Virsa — the Pakistan National Institute for Folk and Traditional Heritage. She has authored three books: Taboo! The Hidden Culture of a Red Light Area, Working With Sharks and Folk Heritage of Pakistan.

I see the #MeToo campaign as a new mechanism designed to expand the space for women to safely speak out against harassment and abuse. Women are recognising that there are many others who have quietly suffered similar degradation. This campaign has also created an awareness of the absurdity of continued male dominance in supposedly ‘modern’ western societies.

Over the past few decades, every region has followed its own path in dealing with patterns of sexual abuse. In Pakistan, our organised struggle started in 1999 after a case was filed by 11 women (eight of them Pakistani and three foreigners) against one man in the UN on charges of sexual harrassment. This person had spoken to every one of these women in an objectionable manner, but because they had stayed silent, his pattern of abuse had remained hidden. When the women began to share their experiences, they learnt that he had used the same offensive phrases with all of them. Thereafter, a joint case was filed by them and, despite serious resistance from the UN management, the women won the case and the man was fired.

After this case concluded, the number of women in Pakistan who were willing to speak out started to increase. Gradually, some took charge of charting out paths seeking justice for their grievances. The movement formulated a policy against sexual harassment at the workplace and, after a 10-year struggle, this movement against sexual harassment culminated in the passage of major legislation.

In 2010, two laws were passed declaring this behaviour a crime. The main piece of legislation mandated that it was incumbent on each organisation in the country to institutionalise this anti-sexual harassment policy. And special ombudsman offices were established in each province to address cases for organisations that had not yet instituted proper mechanisms. This was the first law of its kind in South Asia, but later, similar legislation was instituted in India, Afghanistan and the Maldives. The second law criminalised sexual harassment anywhere it occured in the country under the mainstream Pakistan Penal Code, section 509.

In this case, I can honestly say: #MeToo. I shared my personal role as one of the victims in that UN case in my book, Working With Sharks in 2012. Following that book launch, a small group of us initiated a campaign in Pakistan, called ‘Speaking Out,’ encouraging women to tell their stories. Now, I realise it is time for women to connect globally in a more proactive manner. Social media has opened communication pathways we never imagined even a decade ago.

Our challenge in Pakistan has been to get the law implemented. The private sector, civil society and provincial governments have played a critical role in this. Over the past decade women clearly have been speaking out more. The challenge remains to ensure they get justice. Thousands of cases have been registered and resolved. Nearly every large university in Pakistan has seen the termination of services of at least three or four professors for abuse. Every province has a watch committee actively implementing this legislation. Over 10,000 resource persons have been trained to spread the awareness. We have seen impressive compliance with the legislation in the banking sector and other large private industries. The public sphere has been slower on the uptake, but is doing much better than before the law by establishing regularised complaint and inquiry systems.

The #MeToo slogan goes viral and global. (Bertrand Guay/AFP)

Recently, a little girl of seven was raped and murdered in Kasur. This caused outrage among people across the nation. The media highlighted the issue with discussions on every channel. Common people, professionals, civil society members, politicians and celebrities all came out and protested. The limited capacity of the law-enforcing agencies was highlighted. One clear outcome of this outrage is that because of the ongoing hue and cry, the Punjab government and police were forced to take notice, resulting in the perpetrator finally being apprehended. And now, more cases of a similar nature are being reported in other provinces, which it is likely, would otherwise have been swept under the carpet.

We need to be very careful not to conflate harassment with rape, but they are two ends of a continuum. Both are harmful behaviours with the same root causes, but rape must always be seen as far more severe.

We also never want to fall into the trap that is quickly dividing men and women into warring camps in some western societies. In Pakistan, men are increasingly becoming aware of their behaviour and that of their friends. Over the last three decades, men have been joining in our struggles against domestic violence, sexual harassment and rape, while addressing their own issues of masculinity. We do not want to collectively stigmatise all men for the actions of the bad individuals.

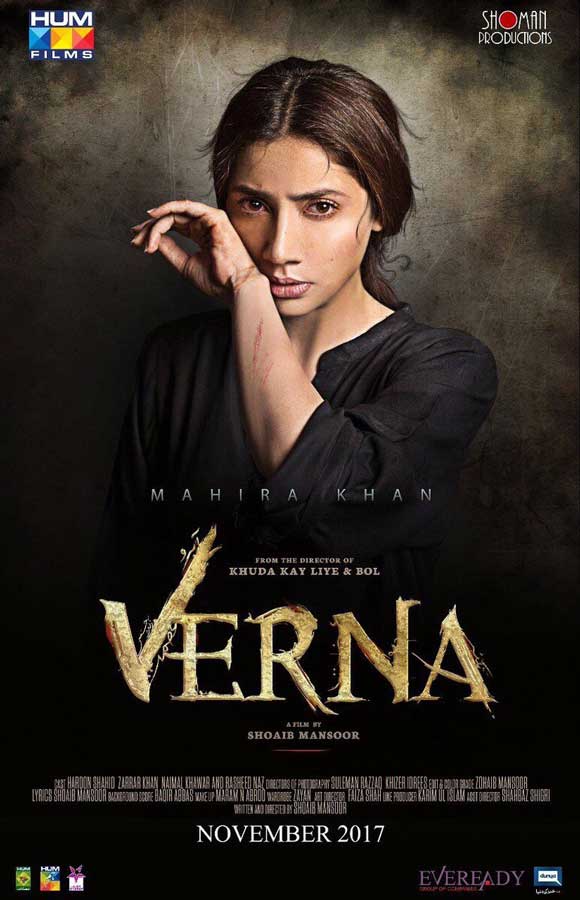

Four years ago, some women created a platform called ‘Pakistani Nari Tehreek’ to spread a new narrative around rape. The group conducted a special campaign in response to the film, Verna, directed and produced by Shoaib Mansoor to highlight the impact of social pressure on rape victims in Pakistani society. Verna also introduced a new Urdu word for rape: zabarjinsi.

Verna has also inspired men to do something about this heinous crime. I just facilitated the training at Mehergarh of 30 men who recently formed chapters of the ‘Pakistani Men Against Rape’ movement in various regions of Pakistan. This not only includes big cities like Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Faisalabad and Peshawar, but also places like D G Khan, Swabi, Bajaur, Mardan, Muzaffargarh, Larkana and Swat.

I was impressed by their yearning to learn more about gender constructs, patriarchy and myths around rape. The men were full of enthusiasm to return to their communities to dispel these myths and to help men more completely understand their own masculinity.

Neither the women’s campaign nor the men’s initiative are donor-funded project activities, being solely motivated by the members’ desire to see real change in our society.

May it be murder, rape, domestic violence or sexual harassment, silence has been the biggest stumbling block when dealing with these issues. The atrocities of those in power will continue to be hidden behind the wall of silence unless we have a better way of enabling women to speak out safely.

Stigmatising the victim by propagating myths and cloaking the whole issue under “it’s her fault” remains standard practice. Both men and women use this to shame the survivor into silence. “If a woman is on the right path; no one can touch her.” This is a part of our socialisation and every parent teaches this myth to their daughters.

The silence of the victim becomes a lock on the door. We need to open that door, and hold it open, if we want to deal with these issues as a modern society.