To the Victor the Spoils

By Amir Zia | Cover Story | Published 6 years ago

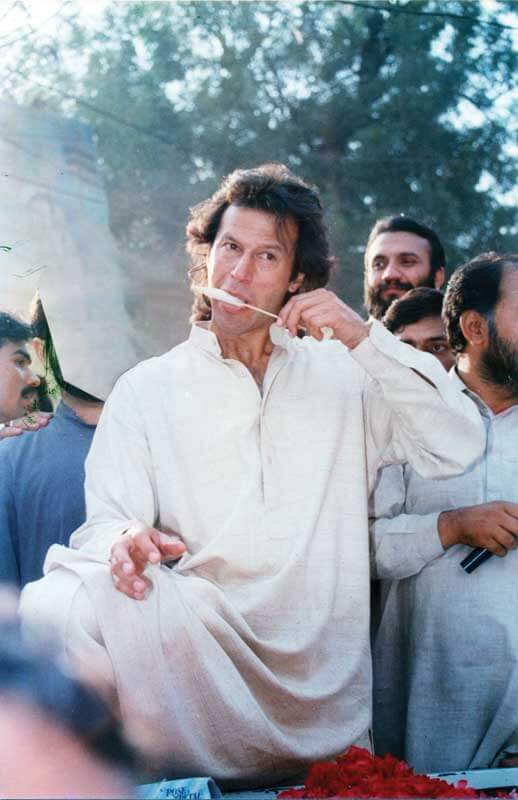

After a 22-year long gruelling journey in the political wilderness, Pakistan’s most internationally recognised sports celebrity and ladies’ man-turned-philanthropist-turned-politico, has managed to don this dream cap too.

The vagaries of Pakistani politics being what they are, there are no certainties or absolute truths.

After decades of rule by the two families that have virtually institutionalised dynastic politics, each laden with the baggage of alleged corruption, nepotism and even murder, Pakistan was ringing with a call for change. Imran Khan and his party offered just that: a radically different alternative. The PTI carved out a constituency by cutting a swathe across different political and ideological divides. It captured the imagination of the centre, the moderate and the conservative right, apolitical liberals, the westernised elite, the young and the old. People from all classes and ethnic groups, hailing from all the four provinces, harkened to the PTI call, making it the first political party after Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s PPP to lay down roots across Pakistan.

But hell apparently hath no fury like political demagogues scorned. And so all the traditional political forces — from the far-right to the self-professed political moderates, from sworn enemies to friends of convenience, and every political force in-between that has been spurned in the 2018 election — have come together to form a new grand alliance to counter the PTI.

Having been formally nominated as Prime Minister-designate by the PTI and with the additional votes needed by the induction of independents and an uneasy alliance with the MQM, Khan is, however, now set to take his seat at the helm and get down to the business of governance in earnest.

The question on everyone’s minds is, can he deliver? The near miracle he has vowed to bring about, is a tall order by any standard. But two decades later, Khan is no longer the political novice he once was. Years of setbacks in politics have taught him pragmatism, as opposed to the puritanical and black-and-white approach he began with. This was evident when he embraced the ‘electables’ with open arms and shook hands with those whom he had once rejected.

The Imran Khan of 2018 appears in no mood to repeat the mistakes of the 2013 elections. To begin with, he has clearly realised that the PTI could not have translated its popularity into electoral victory with inexperienced candidates. Hence, the induction of some tried and tested politicians who might have been undesirable in the past. Yet, against the advice of conventional politicians, he has remained uncompromising in his stance against the country’s two oldest mainstream parties — the PML-N and the PPP. For him, Nawaz Sharif and Asif Ali Zardari are two sides of the same coin. This has resulted in the convergence of the PML-N’s and the PPP’s interests against the PTI, as is evident in their cooperation in the joint opposition.

Khan has made conciliatory statements in respect of neighbouring countries, even while emphasising that Pakistan seeks equality in its relationship with its peers. He has also unequivocally declared that he will seek to rid the country of its begging bowl vis-a-vis international financial institutions.

“He ran a hectic and punishing election campaign,” said Senator Faisal Javed Khan, who joined the party in 1996 at the age of 15 and who has been by Imran’s side in most rallies, including the recent election campaign. “During the last 14 days of the campaign, Imran addressed 60 public meetings… at times, seven public meetings in a day, criss-crossing from one province to another. His younger followers were exhausted, but Imran went on non-stop, skipping meals, preparing speeches and offering prayers during helicopter rides or while on the road — often drenched in sweat from head-to-toe during the oppressive July heat,” added Faisal. “He always says that the match is not over till the last ball. And so it was.”

But with only a slim majority in the National Assembly, making good on election pledges and victory vows, will be a Herculean task. The precarious position of the country’s economy might force the new government to, once again, turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout, or to friendly countries for injections of funds needed to avoid the looming balance of payment crisis. This means tough austerity measures, higher inflation and unpopular reforms that will hit the common man the most, as little money will be available for development and the social sector.

These challenges fail to deter Khan’s supporters, who believe that their leader can deliver come rain or sunshine. “People told him that he could never play Test cricket or become a fast bowler, but he did,” said Faisal. “He and his team were ruled out of the World Cup, but he won it… all experts said that a cancer hospital that aims to treat poor patients free-of-cost, could never be built or sustained, but he did both.” He contends that now, under Khan’s Prime Ministership, “we will make the new Pakistan he has promised, that will treat rich and poor alike, and provide justice to all.”

Hunaid Lakhani, founder of Iqra University and its former chancellor, who came all the way from the United States to contribute to Imran Khan’s electoral campaign in Karachi, also claims he has no doubt about the success of his leader as premier.

“Leadership matters,” he said. “Imran inspires people. They trust him with money — including the Pakistani diaspora scattered all over the world. He will make possible what appears impossible.”

And like Lakhani, many expatriate Pakistanis dashed to Pakistan to cast their vote and participate in the election campaign. They aimed to realise the dream of Khan’s ‘Naya Pakistan,’ which may appear elusive and ambiguous to his critics, but is viewed by supporters as representative of diversity and an openness to personal intepretation.

The slogan has struck a chord with hundreds of thousands of Pakistanis —angry and frustrated with decades of corruption – the loot, plunder and misrule of past governments. Khan’s uncompromising pledge to change all of that has captured their imagination.

Clearly, even after decades, Imran’s personality cult and fan club remain intact. In many constituencies, he asked voters to ignore the candidates and just stamp the symbol of the bat. “I take their (the PTI candidates) full responsibility,” he repeated at various meetings.

The 2018 election campaign was different from previous ones. Despite his fan following, larger-than-life image and personal charisma, he failed to politically capitalise on any of these assets in previous campaigns. The PTI was routed in its maiden election appearance in 1997 — the party was unable to win even a single seat. In 2002, Imran managed to secure a single seat in the National Assembly. In 2008, he boycotted the general elections and since then, was widely dubbed a ‘failed politician’ akin to Asghar Khan.

The first surge in the PTI’s fortunes came in the 2013 elections, in which it emerged as the third-largest party in the National Assembly and the second-largest in terms of securing the popular vote. Yet, the dream of Imran becoming prime minister continued to remain elusive. He was seen as a political novice singlehandedly trying to bring down the entrenched Goliaths of Pakistani politics.

While his newly politicised fans followed him, Imran’s political posturing and positioning made him unpopular among liberals and leftists. The sobriquet ‘Taliban Khan’ was conferred on him because of his conciliatory statements towards the Taliban and insistence on dialogue rather than war with the movement. Maulana Fazlur Rehman of the JUI F dubbed him a ‘stooge of the West’ and a ‘Jewish agent’ – presumably on account of his marriage to Jemima Goldsmith, who was of a Jewish heritage, never mind that she had converted to Islam.

Khan’s stance on the blasphemy laws, women and the feminist movement, earned him the wrath of many. While some believed that his conservative views were aimed at winning the electoral support of the conservative and orthodox sections of society, others alleged that he had actually become increasingly orthodox in matters of faith.

Although many of Imran’s rightwing, liberal and left-wing critics enjoy little grassroots following, their clout on the traditional and social media amplifies their voices. These voices, coupled with the influence and propaganda of mainstream political rivals, made a lethal combination as Pakistan’s largest media groups turned their guns on Khan and his team. There were no-holds-barred attacks — from the targeting of his personal life, to questions surrounding his political positions.

The 126-day long Islamabad dharna of 2014, against the alleged rigging of the 2013 polls and Nawaz Sharif’s misrule, helped transform the PTI into a party with popular appeal and helped expand its base from the urban middle class and the elite, to rural areas. It simultaneously engendered another barrage of allegations against Khan. Political rivals of all hues and shades now called him an ‘army puppet,’ used to weaken democracy in the country. ‘Ladla’ (darling of the establihsment), was another epithet coined for him.

These allegations continue to follow Khan, post-elections. His faithful followers trash them, while his rivals and critics reiterate them on every platform – including the media and the courts of law.

Imran’s supporters, however, allege that he is the only national leader who has not benefited from any military ruler. While both Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif started their political careers under the wings of military dictators, Khan carries no such stigma, they claim.

And so there he is, on the eve of assuming office as Pakistan’s 19th Prime Minister, having graphically demonstrated the fruits of tenacity.

“The first lesson for a man who wants to achieve something, is that there are no shortcuts in life,” Khan said in an interview in July 2017. “You make goals in life and then you pursue them. Only those succeed who do not give up. They stumble, but then they rise again and assess why they fell. They analyse their shortcomings. People do take potshots at such individuals — I have been ridiculed my whole life — but a person who is his own best critic succeeds eventually. This has been my life, without any shortcuts. I dreamed big and pursued my dreams without fear and with no intention of giving up.”

Amir Zia is a senior Pakistani journalist, currently working as the Chief Editor of HUM News. He has worked for leading media organisations, including Reuters, AP, Gulf News, The News, Samaa TV and Newsline.