To Screen or Not to Screen

By Ammara Ahmad | Movies | Published 6 years ago

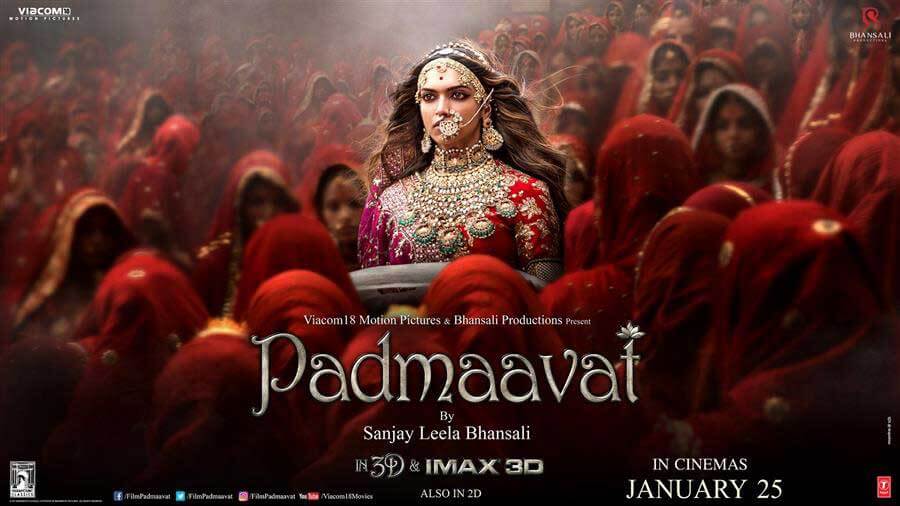

Posh cinema houses with marble floors and leather seats; stalls of popcorn, nachos and fizzy drinks — the screening of Indian films in Pakistan’s myriad multiplexes has reinvigorated the local cinema industry, as well as its mall culture. Dozens of Bollywood films are presently being screened in Pakistan, though this is just a fraction of the number of films released in India. The ones that make it to Pakistan are usually the major productions — such as PK, Dilwale, Padmaavat and Secret Superstar — on which the local film distributors and cinema-owners generally make big bucks.

Pakistan has to produce at least 50 to 65 films annually to provide the audiences with a new film every week. And needless to say, those films and their stars need to lure viewers into theatres. The likelihood of this happening any time soon is relatively low and therefore, Indian films are crucial to keep the cinema-going culture alive in Pakistan. Pakistani films can thrive only when there are enough cinema screens, and the footfall to match.

In the past four years, Pakistani actors like Fawad Khan, Mahira Khan, Sajal Aly and Saba Qamar had worked in Indian films, but that changed after the September 2016 attack in Uri, India. Pakistani actors were banned from working in Indian films by the Indian Motion Picture Producers Association and, in retaliation, the Pakistan Film Exhibitors Association stopped exhibiting Indian films, erroneously assuming that Lollywood could reinvigorate the local cineplex culture on its own.

That was a serious miscalculation. Businesses that had huge investments revolving around the cinema industry, started to sink rapidly and the self-imposed restriction on the screening of Bollywood films was removed by the Pakistan Film Exhibitors Association before the year ended. Yet even now, some major Indian productions have not been allowed to be released in Pakistan, the latest being the Kareena Kapoor-Sonam Kapoor starrer Veere Di Wedding, and the reasons proferred are often perplexing. Pakistani films like Bol, Khuda Key Liye and Manto made it to India — but such releases have been few and far between. Moreover, most of them were shown at film festivals. Commercial films (Bin Roye, Actor-in-Law, Na Maloom Afraad) that could have appealed to the general public, like the Pakistani TV serials that are hugely popular in India, have yet to reach Indian audiences.

For an Indian movie to be screened in cinemas across Pakistan, the distributor must first give the Ministry of Information a synopsis of the film, following which the Ministry issues a No-Objection Certificate (NOC) for a one-time viewing by the respective censor boards. The distributor then has to pay customs duty on importing the film.

There are three censor boards in Pakistan now — one in Islamabad that censors films for release in the Northern Areas and the federal capital; the second in Lahore for Punjab; and the third in Karachi, which allows a film release in Sindh and Balochistan. Each board comprises official members (govt department representatives) and non-official members, and their numbers vary. However, a certain quorum (at least four) has to be reached for the viewing and at the end of every film screening there is a discussion among the members. They either suggest edits or issue a certificate without any cuts.

Mobashir Hassan, who heads the Islamabad Censor Board, says, “We are some 20 members — five government officials, 13 private and two former government employees. We follow the Censorship Code of 1980 and the Motion Picture Ordinance of 1979, both which still serve as the yardstick.”

“Now films need an approval from the censor board of each region — Punjab, Sindh, and Central,” says Ather Jawed Sufi, a five-time member of the Censor Board and current chairman of the Pakistan Film and TV Journalists Association ( PFTVJA). “Previously (before 1971) one certificate was valid for the whole country,” he continues. “One could get it from Karachi, Lahore or Dhaka. Now, if Karachi rejects the film, it will not be released in Sindh and Balochistan. This requires three times the expenditure and the paperwork.” Each board charges a censor fee for foreign films — Pakistani films are exempt — and requires separate documentation.

Indian films can come to Pakistan only through registered distributors. And then distributors are mostly interested in movies emerging from large production houses that include superstars like the Khans, Akshay Kumar and some of the Kapoors. But most of the well-known stars have only one or two releases annually, and the distribution networks compete over these few films.

Film censor boards are required to be mindful of two factors when censoring a film — it should not be anti-religion, or anti-Pakistan. However, within these parameters, there have been wide variations in interpretation. Otherwise, certain films on love and relationships, such as Kapoor and Sons (which deals with the subject of homosexuality), Ae Dil Hai Mushkil and Befikre (both of which had steamy scenes) would not have been released locally. And films based on Hindu mythology, like Bahubaali 2, would have been banned. But this was not the case.

Also, Indian films like Sultan and Bajrangi Bhaijaan that are innately nationalistic and have empowering tales of heroism that present India in a very positive light have been screened here. Fortunately, the censor boards are not fixated on these two issues.

However, the Amir Khan-starring Dangal, a wonderfully inspiring film, was not allowed to be released, as it plays the Indian national anthem in one scene when the heroine wins an award in wrestling. Pakistan’s censor board wanted it silenced and the producers didn’t agree. Consequently Dangal, with all its feminist undertones and international successes — it earned $59.70 million in China in just 10 days — did not reach the Pakistani viewer, not via the big screen anyway.

In February this year, the film Padman, starring Akshay Kumar and Sonam Kapoor, was released across India. It was about menstrual hygiene and sanitation — a taboo subject in both India and Pakistan alike. But the film was not awarded an NOC by Pakistan’s Ministry of Information. However, according to Muhammad Usman, an official at the Ministry of Information, it was not about censorship at all. “There was a clash between two distributors, both of whom claimed they had distribution rights for the film and we could not issue an NOC until this issue was resolved. And it wasn’t.”

At the start of March this year, Pari, a horror film produced by and starring Anuskha Sharma, was due to release in Pakistan. The posters were visible on multiplexes across Lahore. However, there was a last minute ban. Mobashir Hasan, chairman of the Islamabad Censor Board, confirmed that the black magic in the film was shown to have been done with a mix of Quranic verses and Hindu mantras. Therefore, the film was not allowed to be released here.

At the start of March this year, Pari, a horror film produced by and starring Anuskha Sharma, was due to release in Pakistan. The posters were visible on multiplexes across Lahore. However, there was a last minute ban. Mobashir Hasan, chairman of the Islamabad Censor Board, confirmed that the black magic in the film was shown to have been done with a mix of Quranic verses and Hindu mantras. Therefore, the film was not allowed to be released here.

In January last year, Raees, a much anticipated Bollywood film starring Shah Rukh Khan opposite Pakistan’s Mahira Khan, scheduled to be released in Pakistan, was banned. In Raees, Khan plays a Gujrati Muslim bootlegger during the 1980s alcohol ban in Gujrat. The protagonist is a mafia don with a benevolent side — he doesn’t believe in terrorism, but is trapped in a terror attack and unfairly dealt with by the police.

The ban on Raees caused a tremendous loss to the distributors and cinema owners here. Additionally, on the Indian side there was another problem: Shah Rukh Khan had to delay its release in India and negotiate with Shiv Sena and Maharashtra Navnirman Sena, to retain the Pakistani actor in the film. There were fears that the film would not be allowed a screening in Maharashtra. Nevertheless, Khan put his foot down when there was pressure on him to replace Mahira. Interestingly, while an Indian producer took a stand for a Pakistani actor, the latter was let down by the Pakistan government when it banned the film for reasons understood only by them.

Film producer Satish Anand, the distributor for Raees says that Raees was approved by the Karachi Censor Board but the decision was overruled by Islamabad. “The Islamabad Censor Board overrides the decisions of the other censor boards even though it is not legal,” says Anand. “The Lahore and Karachi Censor Board look up to the Islamabad Censor Board to see which way it is leaning.”

He adds that once the rights of a film are bought and it is not issued a NOC by the censor board, the money is not refunded by the producer. The distributors can get other films in exchange for the banned film but the distributors often face losses in the process. Anand also shared that the publicity material is either imported or printed locally long before the prints of the film arrive for review by the censor board. The films typically only arrive a week prior to the release and to get banned at the last minute, just before the world release, causing tremendous loss to the distributors.

At the end of 2017, Tiger Zinda Hai, a huge release starring Salman Khan and Katrina Kaif, was banned. The film revolves around the 2014 abduction of Indian nurses by the IS in Iraq. Salman Khan plays a RAW agent collaborating with Kaif, an ISI agent. They fight the terrorists together and, eventually, the Pakistani and Indian flags are raised together, in Iraq, thus taking the India-Pakistan friendship to a new level in our imagination. This film, too, was not allowed a release on patriotic grounds, which was also the fate of the first part, Ek Tha Tiger.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat generated tremendous controversy in India, even though the film’s content was entirely fictional, for supposedly denigrating the Rajputs by showing one of their queens falling in love with the Muslim King, Allaudin Khilji. Apparently, there was only one romantic dream sequence between Alauddin Khilji and Padmavati, which was subsequently deleted because the Rajputs and the Kami Sena threatened cinema owners against the screening of the scene. But much to everyone’s surprise, this film, which glorified the caste system, promoted the not-so-modern tradition of johar — whereby a woman commits suicide to avoid the “dishonour” of rape, depicted a relationship with a homosexual and above all, showed Allaudin Khilji as a barbaric and lusty ruler – was released without any cuts in Pakistan.

Sometimes, instead of banning a film, the censor board requests the distributor to remove certain scenes, to secure a film’s release and on the rare occasion, an adult-rating certificate is issued.

“We couldn’t have released a film like Baby for instance,” says Fakhar-e-Alam, TV actor and host who headed the Sindh Censor Board between 2013 and 2016. “The entire film was about the Mumbai terror attacks and presented Pakistanis as the culprits,” he continues. “And then there were films like Udta Punjab, which had scenes in which drugs were tossed into India from Pakistan. And there was one scene where a drug-production unit had Quranic verses written on its walls, hinting that it was run by a Muslim. These scenes were deleted on the suggestion of the censor board, and eventually the film was released.”

“Let us not divorce ourselves from the reality of our country,” continues Fakhar-e-Alam. “There are extremist elements and they could have started an entire movement against cinemas, just because a Muslim bootlegger was shown on the screen (in Raees). Also, the Indian national anthem being played in the middle of a film (Dangal) could have provoked extremists to burn down cinemas. We are taking baby steps to re-establish Pakistan’s film industry and want to be cautious. A tiny misstep could push us back in time.”

“We have to ensure that the content of a film is not vulgar and does not hurt anyone” – Usman Peerzada, Vice Chairman, Punjab Film Censor Board

Is the certification process the same for each of the three censor boards in Pakistan?

Yes, exactly the same.

What are your concerns, as a member of the censor board?

You see, I am not sitting there to check out if a film is well-made or not. My job is not to teach film-making. The Censor Board’s job is merely to see that the content of a film does not hurt anyone, religiously or politically, and that there is no vulgarity. We look at the basics. Every censor board in the world does that.

Then why do some films get approval from one censor board and not from others?

Islamabad shouldn’t have a censor board. It doesn’t make sense, After the 18th Amendment these powers have been devolved to the provinces. Punjab is independent; why should we take any orders from the centre?

Does the Islamabad Censor Board override your decisions?

They don’t have any legal standing to do this.

Some films like Raees and Udta Punjab were banned, without assigning any cogent reason.

Have you seen Raees? It shows a Muslim as the country’s biggest gangster. That’s how they view Muslims — as gangsters. This is a strategy of Indian cinema. Gujrat is the most sensitive area in terms of communal relations; that’s the state where there was a genocide of Muslims, when Modi was the chief minister. You are making a film in that state called Raees, and you show a Muslim as a don, and additionally you show Muslims attacking Hindus when a Hindu festival is in progress.

Distributors complain that their films are not issued censor certificates till the last day; consequently they end up incurring heavy financial losses.

The distributors are the ones who are responsible for the delay. They need to get a film censored 10 to 14 days before its release date.

Why was a film called Padman on the important theme of menstrual hygiene, denied a censor certificate?

I don’t know. I was not in the country. But apparently, this was a unanimous decision of all censor boards in the country that the film should not get an NOC. If it were left to me, I would have permitted Padman to be released.

Drugs pose a serious problem in Pakistan, so why was Udta Punjab, based on the critical issue of drug abuse, banned?

It was a very good subject actually. It dealt with the huge drug addiction problem that India faces, especially in Punjab. However, the movie puts the blame for this problem on Pakistan, by showing that heroin etc, are being smuggled by us across the border. The Islamabad board raised an objection because the film shows our border security being involved in the smuggling.

Some of the decisions of the censor boards are totally absurd. How was a film like Padmaavat that showed Allaudin Khilji and his men as being totally vile and uncouth and all the Rajputs as being highly cultured and civilised, allowed to be released in Pakistan?

Padmaavat wasn’t based on historical facts, it was make-believe. They did, however, take characters from history [and distorted them]. They painted the Muslim ruler, Allauddin Khilji, as a barbarian. Even though he was a creative man, they portrayed him as a clown.

Which are some of the films that were denied a censor certificate by you?

Ragini MMS 2. I banned it in Punjab. I didn’t want my youth watching porn. I thought it was not right for young minds. There were two others, but I can’t remember their names.

What has been the greatest advantage of allowing Indian films to be screened in Pakistan?

The cinema owner has benefited the most. We have supported Indian films because we believe free trade is important for any industry. If vegetables like onions can be traded, why not cinema? But film trade is one-sided at the moment. Indian films are being screened in Pakistan, but Pakistani films are not being allowed in India. They will burn a cinema house if a Pakistani film is released there, given the present atmosphere in India.

While this [one-way] film trade has helped sustain Pakistani cinema and many new cinema halls have been opened, the cinema-owner is choking the Pakistani filmmaker by taking 50 per cent of the earnings. Of the remaining 50 per cent, 20 per cent is taken by the distributor and only 30 per cent is left with the producer. We need to fix this imbalance. We have apprised the government of it. The government should move in to accord protection to the producer. The screening of Indian films can stop any minute — whenever relations between the two countries take a downturn. Until and unless we empower our industry and produce more films, Pakistan’s film industry will always be lagging behind.