The Unsung Heroes

By Vaqar Ahmed | Bookmark | Published 6 years ago

There are two main types of mountain-climbing. The first is called the Alpine style, in which the mountaineer attempts the climb solo with minimal gear, and often no oxygen, to make a quick dash up and down the mountain. This technique is dangerous and not used by too many climbers. The second, and the most popular, is the Expedition style of climbing. The expedition members set up camps along the way to the peak, to provide a steady source of supplies and a place of rest for the climbers. High Altitude Porters (HAPS) are an integral part of such organised expeditions.

It is actually grossly incorrect to call them porters! The HAPS are, in reality, the linchpin who provide three key services to an expedition: they carry the tents, the heavy climbing equipment and the food to the camps; they act as porters, as guides and as trail-breakers at the higher altitudes. And, perhaps most importantly, it is the HAPS who provide the search-and-rescue-support when climbers are lost on the mountains.

HAPS have long been the neglected heroes in the annals of mountain climbing. More HAPS have lost their lives than the climbers who hire them, yet there is scant literature on these unsung heroes of the mountains. The only other book that has focused on the HAPS is Buried in the Sky. The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers on K2’s Deadliest Day by Peter Zuckerman and Amanda Padoan about the Sherpas of Nepal. It is, therefore, very refreshing to see a book that talks exclusively about the life, work and achievements of the HAPS of the Shimshal Valley of Pakistan.

The author is a German, who teaches English and Latin in Germany. She fell under the spell of the Shimshal Valley when she visited Pakistan, as part of an expedition, in 2002. Since then, she has visited the valley every year and often stayed there for extended periods of time. Shimshal Valley is located in the Hunza district of the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan. The valley is accessible from a road that branches off from the Karakoram Highway near Passu.

Fladt states the purpose of the book in the very first line of the introduction. “They deserve recognition,” she writes. She mentions that while the Sherpas of Nepal have gained international recognition and are thus well paid and lead more prosperous lives, those providing the same services in Pakistan are compensated very poorly.

The first part of the book is a short description of the Shimshal Village, the people who live there, and a list of the five Pakistani 8,000-metres peaks. These peaks are K2 (8611 metres), Nanga Parbat (8,125 metres), Broadpeak (8,047 metres), Gasherbrum 1 (8,068 metres), and Gasherbrum 2 (8,035 metres).

The second part of the book contains the life sketches of 18 HAPS and climbers from Shimshal based on interviews the author conducted with them. All of these HAPS have reached the summit of at least one of the peaks — all above 8,000 metres.

The stories feature some of the legendary climbers like Rajab Shah, the only Pakistani to reach the summit of all five peaks. Sadly, he passed away in 2015. Then there are fascinating accounts of self-made ace climbers like Qudrat Ali and Shaheen Baig, and other HAPS who helped expeditions achieve the glory of reaching the summit, and, at times, reached the summit themselves. However, there is a palpable presence of death in all the stories. Some pictures in the book of the families of the HAPS who lost their lives on the mountain are truly heartbreaking.

There are stories of HAPS seeing climbers falling to their death and then locating and carrying their bodies to the base camp. The accounts of the madness of winter climbing literally run a chill down your spine.

The book demonstrates that the hardest tasks during an expedition are mostly carried out by the HAPS. Besides carrying 16kg of equipment and supplies each, they break the trail and set up fixed ropes to allow the mountaineers an easier climb. They are the ones to whom the expedition turns to when a search mission is carried out for missing climbers, and for help in bringing down injured climbers from high altitudes to the safety of lower camps.

Even when death is averted, there is still immense pain and suffering due to high altitude sickness, extreme weather conditions, lack of food and sheer exhaustion. The HAPS go through all this for a paltry monetary compensation. No wonder then, that the younger generation of Shimshalis are turning to education so that they do not have to depend on the ill-paying and extremely difficult work of climbing mountains.

This book is clearly a labour of love. It has been written with empathy and thoughtfulness while avoiding romanticism. The book is very informative and provides a much greater understanding of the people of this this area who have distinguished themselves with their skill, courage, stoical attitude, hardiness, and a sense of adventure.

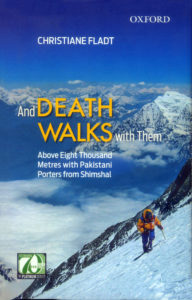

And Death Walks with Them is a valuable addition to the literature on mountain climbing the lofty mountains in Pakistan. What’s more, Christiane Fladt has succeeded in her objective of bringing recognition to the climbers and HAPS of the Shimshal valley.

The writer is an engineer by training and a social scientist by inclination.