The Islamic Republic of Saudistan?

By Raza Naeem | News & Politics | Published 10 years ago

“King Saud had brought with him a box full of gold, which proved almost-impossible to carry for Karachi’s labourers. He sold this gold in Karachi and kindly granted ten lac rupees to Pakistan. It was decided that this money would be used to build a colony for poor immigrants which would be named Saudabad.”

We live in strange times. When Saadat Hasan Manto wrote these words, exactly 60 years ago this month, Pakistan had just begun life as a nascent post-colonial state where the constitution had yet to be drawn, and the unelected military, bureaucracy and feudal aristocracy called the shots.

After the withdrawal of the British from India, any pretence of independence that Pakistan’s ruling elite felt in its domestic and foreign policies, was replaced by the warm and firm embrace of the United States. Later came the abject surrender to the Saudis, not totally disapproved of by the Americans, who akin to their patronage of Pakistan’s rulers, became the new sponsors of the desert autocracy following the waning of British influence.

There is, however, a vast difference between then and now, particularly when it comes to Saudi beneficence towards Pakistan. Arab Sheikhs bearing gifts do not carry with them good tidings for perpetually-indebted Pakistan. If, in the 1950s, they brought some hope for the poor along with the gold, now their visits carry a heavy price tag, despite assurances to the contrary from the country’s financial mandarins after the latest Saudi bequest of $US 1.5 billion in a scarcely entertaining drama at the national level. And this time, the heavy price-tag might end up consuming Pakistan itself.

Contemporary Pakistan is more sectarian and intolerant than it was during the 1950s, even though ardent debates were taking place then, in an albeit unconstitutional parliament, regarding enshrining a role for Islam and Allah as opposed to popular sovereignty. The country had always been dependent on Saudi oil, but its reliance on desert Islam started with its ruling elite backing the wrong side in the Cold War.

Pakistan was a member of the Baghdad Pact, which interestingly grouped together mostly Sunni client states of the United States — Turkey and Iraq included — with the exception of Shia Iran. Interestingly, Saudi Arabia was not part of this anti-Communist alliance. But the Baghdad Pact on one hand, and Saudi Arabia independently encouraged by the United States on the other, especially during the Eisenhower administration, attempted to weaken Gamal Abdel Nasser’s leadership of the Arab world as the US worked to secure Arab oil supplies. Ironically, Shia Iran and Wahhabi Saudi Arabia were united in this instance. Pakistan, being an American client state, and due to what was domestically being played out as a dependence on cheap Saudi oil, put in its lot with the Americans and the Saudis. But American attempts to build up King Saud as an alternative to Nasser at that time failed.

With the defeat and collapse of Nasserism and secular Arab nationalism in the Arab defeat to Israel in 1967, radical Islamic parties and groups became the basis of a new imperialist strategy to destroy secular and nationalist alternatives across the Muslim world. The decision of Pakistan’s ruling elite to import Saudi influence must be understood in this context. But it not only imported sectarianism and intolerance into Pakistani society, but also weakened democracy. That, of course, was only inevitable. It bears repeating that Saudi Arabia is the leading autocracy in the Arabian peninsula in a sea of monarchies and has always used its oil and petro-dollars to subvert democracy in its neighbourhood.

One only has to look at the subtle way the Saudis, mid-wifed by the Americans, brought about a reactionary ‘union’ of tribal North and communist South Yemen, supported the Saleh dictatorship and continue to subvert democracy there, with Yemen being the only parliamentary democracy in the Saudi neighborhood. The same is the case with the brutal suppression of the democratic uprising in fellow-Wahhabi-led Bahrain in 2011, which has long been a Saudi playground for the excesses of its unscrupulous royals.

Pakistan was never part of the Saudi neighbourhood, but because of some hasty and short-term decisions by its ruling elite, it gradually became an influential playground for Saudi Wahhabism and power politics. Even before the fall-out from the Afghan jihad during Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship, it was the nominally secular, democratic government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto which began the process of sending thousands of poor migrants to Saudi Arabia, thus cementing the country’s economic dependence on oil and remittances from that country. Many of these migrants, while braving often inhuman (or subhuman) work conditions in Saudi Arabia, then became vectors and carriers of Wahhabism when they returned home.

Never mind the opportunistic role of our own politicians in exploiting religion for their personal ends, whether it was Bhutto’s decisions to declare Ahmadis non-Muslims or the imposition of Nizam-e-Mustafa and the banning of alcohol consumption; or the havoc Zia played with a self-serving (Saudi) reading of Islamic law. The overthrow of Bhutto by Zia opened the floodgates to Jihad Inc. funded largely by the Saudis and organised by the Americans. The conclusion of that war spawned a whole angry generation of youths across the Muslim world, who, piqued at American ‘betrayal,’ decided to take the war to their own countries, with disastrous results for the Pakistani state and society in particular.

Notwithstanding the fact that Saudi Arabia is now the preferred destination of discredited dictators and failed politicians from Idi Amin and Ben Ali to Musharraf and our present Prime Minister, this dependence on Saudi oil, remittances and power politics has resulted in creeping Saudiisation in Pakistan over the last two decades.

As I write this, a Christian has been sentenced to death in a notorious ‘blasphemy’ incident in Lahore’s Joseph Colony — one more victim of the blasphemy law that was first introduced by the Saudi-obssessed Zia-ul-Haq. In the region comprising Pakistan, Islam was introduced to the locals not at the point of the sword, as local primary and secondary school textbooks are wont to repeat in their incessant glorification of Muhammad bin Qasim, but through the syncreticism of the Sufis.

Apart from the war on our own people, whether they be Shia, Ahmadis or Christians, or even Deobandis/Barelvis for that matter, there is the softer, passive, therefore more disturbing face of Wahhabism. Among the women, this started out initially as an outward manifestation in an increasing trend of wearing of the hijab, niqab, burqa — and the culturally alien abaya — and the rise of the mehfils of dars, by televangelists like Farhat Hashmi of the Al-Huda Foundation, Amir Liaquat Ali and Zaid Hamid, who often espouse extremist opinions, albeit in liberal garb, appealing to conscientious middle-class pieties.

This trend has been helped by the born-again conviction of many of Pakistan’s famous cricket and music icons. Thousands of members of this group propelled Imran Khan, himself a born-again Muslim, and his Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf to prominence in the national elections last year. Interestingly, Khan has been nicknamed ‘Taliban Khan,’ and this has gone hand-in-hand not only with his own views about the role of women and form of justice in Pakistan, but also in the totally unpredictable compromises his party’s provincial government has had to make in Khyber Pakhtunkhuwa, kowtowing to and defending the inexcusable actions of the Taliban.

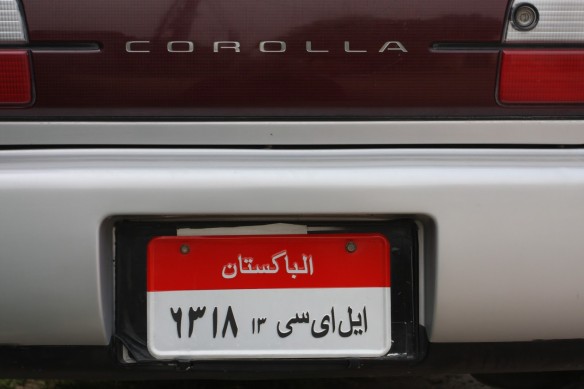

And so, increasingly, Saudiisation among Pakistan’s younger generation goes viral, manifesting itself in the ‘new’ car plates flashing Arabic and Arabised variants of the country’s name, and in the replacing of ‘Khuda Hafiz’ by ‘Allah Hafiz’ in our lexicon. The Saudis’ attempt to buy Islamabad with more handouts is ostensibly to lure them into their own camp for their Cold War against a resurgent Shia Iran in the two current Arab flashpoints in Syria and Bahrain. In reality, Saudi politics and strategies might prove to be a dangerous trap which could lead to a debilitating conflict resulting in democracy for the benighted citizens of Riyadh sooner, rather than later. Good as that may be, in the process, it could also seriously push back the chances of a burgeoning democracy in Pakistan for some time.

As the great Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, a scourge of the Saudi elite, pleaded in one of his last poems before his death, addressing the potentates in Riyadh, for the world to be delivered from any further shaikhly profligacy:

“No one! No one wants to usurp your cushy royal seat!

No one is interested in your Caliphate soutane!

Go ahead! Get drunk with your petrol..to the last drop!

Take everything you want!

But please leave us the culture you never had…”

This article was originally published in Newsline’s April 2014 issue as part of the cover story.

The writer is a social scientist, translator, book critic and a prize-winning dramatic reader based in Lahore.