Taking Stock of the Arab Spring

By Hamza Usman | News & Politics | Opinion | Society | Published 12 years ago

All it took was one man setting himself on fire to trigger the biggest wave of revolutions since the fall of the Berlin Wall. As the first elections since the ouster of Zinedine Ben Ali took place in Tunisia where the movement began, in Libya the era of Muammar Gaddafi has finally come to an end, with a victory for the anti-Gaddafi forces. Elsewhere in Egypt, Hosni Mubarak’s downfall in February of this year has made him a criminal reaping the repercussions of what he has sown. Following in the footsteps of Tunisian President Ben Ali, Mubarak’s downfall ushered in a period of hope and optimism as Egypt finally seemed to have embraced democracy after three decades of Mubarak’s oppression. The message reverberated loud and clear: the Arab Spring was in full swing and repressive autocracies that had long governed the region had better beware: their days were numbered.

All it took was one man setting himself on fire to trigger the biggest wave of revolutions since the fall of the Berlin Wall. As the first elections since the ouster of Zinedine Ben Ali took place in Tunisia where the movement began, in Libya the era of Muammar Gaddafi has finally come to an end, with a victory for the anti-Gaddafi forces. Elsewhere in Egypt, Hosni Mubarak’s downfall in February of this year has made him a criminal reaping the repercussions of what he has sown. Following in the footsteps of Tunisian President Ben Ali, Mubarak’s downfall ushered in a period of hope and optimism as Egypt finally seemed to have embraced democracy after three decades of Mubarak’s oppression. The message reverberated loud and clear: the Arab Spring was in full swing and repressive autocracies that had long governed the region had better beware: their days were numbered.

Yet, the Arab Spring has so far managed to accomplish little other than cosmetic changes and big promises. Familiar characters like Mubarak and Gaddafi may have gone the way of the Dodo, but there is little to suggest that stability and true democracy are imminent. The road ahead is jarred with complications. Uprisings have also taken place in Bahrain, Yemen and Syria, but these have so far been unsuccessful as familiar old faces still rule strong. The status quo remains, and one can’t help wonder if the much hyped Arab Spring was, in reality, just a passing breeze instead of the divine wind it was intended to be.

Egypt’s progress toward implementing democracy has been at a snail’s pace, with few developments worthy of mention. The hope and change that heralded the start of the Arab Spring has now petered into a lacklustre crawl. Much of the international community embraced the Arab Spring with optimism, but all that has been achieved thus far is the replacement of an old familiar face with many new ones, all equally recalcitrant and lethargic toward bringing greater change. If anything, the Arab Spring reveals just how complicated the Middle East and the North African region really are. Leaders may depart but regimes still survive. The new hopefuls in Egypt and Libya have their work cut out for them in the months ahead. No one ever said democracy and transition were easy; moving from one system to another requires administrative, constitutional and electoral changes but, more importantly, changes in the mindsets of all citizens irrespective of class or background.

Egypt’s revolution left many Romantics praising the beauty and heroism of the struggle. The protesters persevered, despite numerous odds, and emerged victorious with Mubarak’s resignation. Power was transferred to a military council of 18 members that have not been able to deliver the much-promised changes. In March, constitutional amendments for the elections were approved overwhelmingly in a national referendum. By April however, the slow pace of change resulted in protests and many clashes between the people and the state. Tahrir Square turned violent again. A parliamentary election was due in autumn where legislative powers would be transferred. But so far, this has not taken place. The sweeping executive powers that Mubarak enjoyed were also due to be transferred, but this has not happened. Despite his appearance in court on charges of corruption, the state appears to be taking its time toward democracy, resulting in plummeting popularity ratings for the military leadership. Many speculate that the ruling military was complicit in Mubarak’s repressive rule and therefore will not move swiftly in order to bring about any sweeping changes that may undermine their authority.

The Egyptian revolution witnessed a united polity with one clear demand: the removal of Mubarak. Now, with so many varied groups clamouring for change, it is unclear which direction Egypt will proceed in. Will change be imposed from the top, or will the people manage to organise themselves in a responsible and effective manner for a governance structure? The Muslim Brotherhood, a powerful Islamist party in Egypt, may dominate the voting. If that were to happen, would Egypt become a more hard-line state? Where would that leave the secular parties that embody the true economic and political aspirations of the people in the Middle East’s most populous state? These are just some of the many questions clouding Egypt’s future, lighting a tumultuous road ahead.

The Egyptian revolution witnessed a united polity with one clear demand: the removal of Mubarak. Now, with so many varied groups clamouring for change, it is unclear which direction Egypt will proceed in. Will change be imposed from the top, or will the people manage to organise themselves in a responsible and effective manner for a governance structure? The Muslim Brotherhood, a powerful Islamist party in Egypt, may dominate the voting. If that were to happen, would Egypt become a more hard-line state? Where would that leave the secular parties that embody the true economic and political aspirations of the people in the Middle East’s most populous state? These are just some of the many questions clouding Egypt’s future, lighting a tumultuous road ahead.

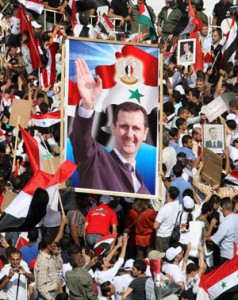

Similar questions abound in Syria. Since protests erupted in March, Syria has been volatile and violent. Compared to Egypt, the movement in Syria has seen greater violence as more and more people have taken to the streets to bring down Assad’s regime. So far, an estimated 2,700 people have been killed and over 10,000 arrested. Despite President Assad removing Syria’s decades-old ‘state of emergency’ that legitimised his rule, the opposition’s rising calls for change have resulted in no hope of compromise between the polarised sides. Compounding Syria’s complications is the religious divide. President Basher Assad and the ruling Ba’athist elite are Alawaite Shias while the majority of the country is Sunni. Christians, Druze and many other sects also exist, creating a hodgepodge of different interest groups. In October, Syrian dissidents coalesced to form the Syrian National Council. As a consolidation of different opposition groups, the shared objective is the ouster of the Assad regime. However, without international recognition, the group has yet to show its capability in governing Syria were Assad to be overthrown or killed in the near future. The Syrian Muslim Brotherhood and the Damascus Declaration group are just some of the players in a sea of different factions and interests. Uniting fractured interest groups into an effective democratic alternative remains Syria’s biggest challenge on the road to stability.

Similar problems plague Libya. Although the Arab Spring is responsible for sparking those preliminary movements in Ben Ghazi that catalysed the rebel movement against Gaddafi, the model for change was very different. While Egypt and Tunisia witnessed the strengths of people’s power, Libya met the foreign hand of intervention. Gaddafi’s 42-year domination of Libya came to an end after NATO air strikes and an armed resistance movement crippled the eccentric strongman’s capacity to govern. His subsequent death in October heralded the end of an era, but also highlighted the problems ahead. The international community’s recognition of the Transitional National Council as the de-facto government of Libya has set in motion a series of developments towards creating a stable government. While the Council has promised to assemble a new cabinet and prepare for elections within eight months, it remains to be seen whether the resistance will continue under his son Saif, who remains at large.

Worse still, the growing influence of Islamists raises questions about the nature of the government that will eventually fill the Gaddafi void, and whether long-needed reforms and liberalisation will actually take place. The absence of a central authority makes Libya’s future rather nebulous. Would substituting Gaddafi’s authoritarianism with a hard-line Islamist government, or worse, a weak central government unable to reach a consensus, be a suitable replacement? To add fuel to the fire, various rebel factions have yet to disarm. Convincing various armed groups to disarm or join the National Army is crucial to Libya’s stability. It’s only natural that those groups and individuals who feel they played a major role in bringing down Gaddafi will now want a share of the spoils. Satisfying various groups, each feeling equally entitled to a piece of the pie presents many problems for Libyans struggling at the moment to provide the bare minimum. Libya’s infrastructure is crippled due to the civil war, as pipelines, terminals and roads need to be repaired to facilitate badly needed oil revenue. While Gaddafi’s ouster should be celebrated as a first step, it is just that: a first step in a long series of necessary developments for Libya’s stability and prosperity.

Worse still, the growing influence of Islamists raises questions about the nature of the government that will eventually fill the Gaddafi void, and whether long-needed reforms and liberalisation will actually take place. The absence of a central authority makes Libya’s future rather nebulous. Would substituting Gaddafi’s authoritarianism with a hard-line Islamist government, or worse, a weak central government unable to reach a consensus, be a suitable replacement? To add fuel to the fire, various rebel factions have yet to disarm. Convincing various armed groups to disarm or join the National Army is crucial to Libya’s stability. It’s only natural that those groups and individuals who feel they played a major role in bringing down Gaddafi will now want a share of the spoils. Satisfying various groups, each feeling equally entitled to a piece of the pie presents many problems for Libyans struggling at the moment to provide the bare minimum. Libya’s infrastructure is crippled due to the civil war, as pipelines, terminals and roads need to be repaired to facilitate badly needed oil revenue. While Gaddafi’s ouster should be celebrated as a first step, it is just that: a first step in a long series of necessary developments for Libya’s stability and prosperity.

Factions and interest groups vying for power continue to plague the Middle East. It’s true that the revolutions are far from over but many of them have succeeded in achieving the bare objective: removing the tyrant. The Arab Spring was a catalyst for change that is still ongoing. Egypt and Libya have revealed the difficulties of replacing a centralised government with an inclusive democratic model. Yemen and Bahrain remain question marks where the movements’ intensity has splintered but not vanished entirely. With Gaddafi gone, all eyes are on Damascus and Assad’s brutal regime. Were Assad and his coterie to fall from grace in Syria, similar problems will arise there. The Arab Spring has bought hope and change in the Middle East, but perhaps it would be a little too premature to assume that everything would take care of itself shortly. Yes, the progress from autocracy to democracy is slow and riddled with obstacles and question marks, but as Tunisia walks away from its elections 10 months after ousting its dictator, there’s hope for anyone else embarking on the tempestuous road of change. But hope itself, is not enough. As developments have shown, removing a leader is relatively easy compared to the real challenges of nation-building that now lie ahead.

This article first appeared in the November 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Spring Turns Frosty.”