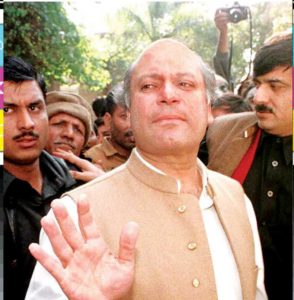

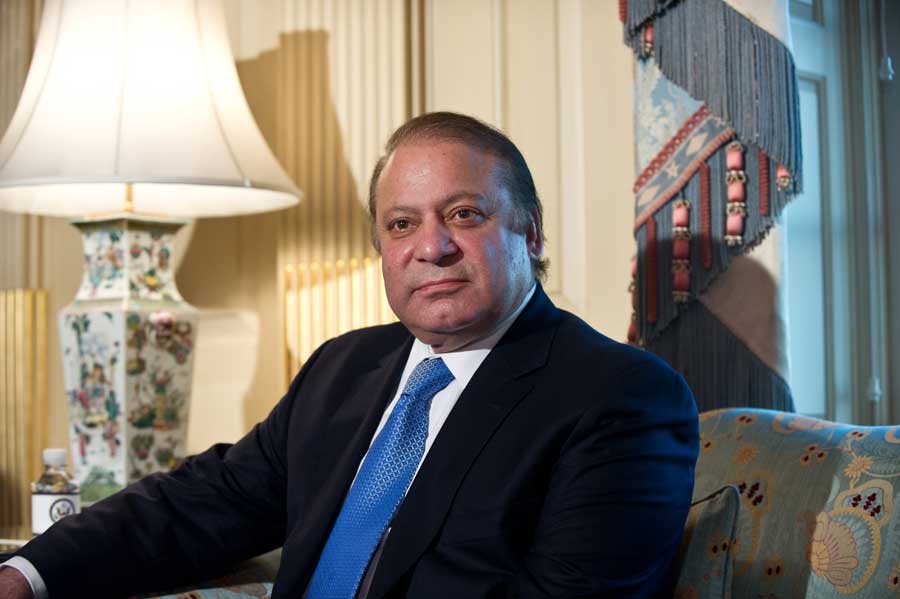

Sharif’s New Avatar

By Aamer Ahmed Khan | Cover Story | Published 6 years ago

Does Pakistani democracy really need Nawaz Sharif? Less than a decade ago, most of our liberal political commentators would perhaps have scoffed at the question and the answer may well have been an obvious one: as much as an earthworm needs salt. But times, they may be a’changin.

Take a brief look at his remarkable political career. A political weapon created exclusively by Pakistan’s mighty military establishment under the watchful eye of its vilest dictator, to be used specifically for souring the delusional democratic dream brought back by Benazir Bhutto in the heady spring of 1986, Nawaz Sharif was meant to be the tool with which the army’s political ambition could either terminate the democratic dream for good, or at least mutilate it to the point where no one was left sure of what it actually meant. Yet he stands today as perhaps the only bulwark against that very same ambition. The accompanying timeline covers the period through which this remarkable transformation has unfolded. The question is: how real is it?

It is not a frivolous query, for a man who seems to have gone through such a fundamental change in a period spanning three decades, there is much that does not seem to have changed at all. For one, his style of governance. Ruling through a kitchen cabinet, preferring to take decisions in isolation rather than in consultation, depending on relatives more than professionals, and promoting a hereditary hierarchy over a political one have remained the key characteristics of his ruling style from day one. If one didn’t know better, it was never too difficult to mistake him for a monarch.

His attitude towards his political contemporaries has shown a similar resistance to change, the strongest example being his disregard for the parliament in each and every tenure, his steady alienation from his political allies, and an ever present ideological vacuum that enables him to oscillate any which way and lose, making him almost perilously unpredictable. As a result, his regard for concepts such as the Constitution has never been very different from that of his mentor, General Zia-ul-Haq.

His attitude towards his political contemporaries has shown a similar resistance to change, the strongest example being his disregard for the parliament in each and every tenure, his steady alienation from his political allies, and an ever present ideological vacuum that enables him to oscillate any which way and lose, making him almost perilously unpredictable. As a result, his regard for concepts such as the Constitution has never been very different from that of his mentor, General Zia-ul-Haq.

And he is no less obstinate when it comes to his economic policies. A staunch believer in buying political support by opening up state coffers to all and sundry, he is anathema to most banking practices. Perhaps the only aspect of his economic model that outdoes his disregard towards banking propriety is his unwavering faith in megaprojects. From the Lahore-Islamabad motorway in the early 1990s, to the infamous CPEC of his current tenure, he is never shy of indebting the national exchequer. Understandably, people’s fundamental needs and the state’s basic responsibilities, such as health and education, have never been at the top of his shopping list.

Yet he stands today as democracy’s great white hope in an environment littered with ailing and ineffective democrats of yore, violently drooling religious zealots, deeply suspect ideologies masquerading as change, a media reduced to a farce, a social media-savvy army and a judiciary that seems to have lost the distinction between legislation and the law. What could have driven a man of Nawaz Sharif’s background to such an exciting new status?

Partly, it is the one thing that has not changed in him after it changed the first time round: his relationship with the army. Some 12 years after he was picked up by a military junta to do its bidding against the democrats, Sharif revolted against his mentors when forced out of the office of the Prime Minister halfway through his first tenure. It is perhaps pertinent to remember that at the time, it wasn’t the democrat in him that rebelled against the dictatorial machinations of the Eighth Amendment which allowed a non-representative army-backed president to force him out, but the resident brat of an emerging industrial empire who had never been taught the distinction between a desire and a need. Sharif, at the time, had publicly vowed never again to rise to power “riding the shoulders of a general,” a rebellion that continues to fester in his mind ever since and a big reason why, since winning a two-thirds majority in the 1997 general elections, he has been arrested, tried for treason, opted for exile, returned to reclaim his political space and risen to the office of the prime minister for the third time in his life, the only constant in these diametrically opposed fortunes being his unrelenting mistrust of the political ambitions of the Pakistan army, one of the largest standing armies in the world.

A larger part in the emergence of a new Nawaz Sharif, however, has perhaps been played by a changing political environment that may have little to do with the man. Since democracy’s revival in Pakistan in 1985, the country’s mainstream political analysis has relied without exception on the basic assumption that when it comes to political manipulations, the army gets what it wants. In all fairness, this analysis is backed by strong historical evidence. A decade-long martial law when public support for the country’s first popularly elected leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto had peaked in 1977, five popular mandates truncated between 1985 and 1999, six interim governments in the same period, another decade of martial law followed by two shortened prime ministerial tenures, and the army’s complete stranglehold over what is generally referred to as an independent electronic media, can only be described as overwhelming evidence of the army’s success in retaining its dominion over Pakistani politics. Hence the assumption that the army always gets what it wants. Yet the 2018 general elections could be the first real test in 33 years for the analysis resting on it.

Compared to his meek acceptance of an exile deal in December 2000, a deal that allowed his entire family and some favorite cooks to leave Pakistan with a 10-year Saudi-backed guarantee of no return, Nawaz Sharif has delivered a historic first: a popular Punjabi leader standing up to a predominantly Punjabi army in its heartland. This is not a Bugti hiding in a cave in Baloch backwaters who could be bombed to oblivion, or a semi-westernised Bhutto from a minority province who could be assassinated at the small risk of a mere week of civil unrest in southern Pakistan, but a home-spun, meat-loving, male, Sunni, Punjabi who recruits his support from the same plains as his nemesis and is now saying enough is enough. More importantly, having been delegitimised from holding public office, it is easier to see him as a man no longer fighting for personal gains but for the idea of genuine civilian supremacy. It may still not be enough, but it remains a challenge unlike any that Pakistan’s uniformed political engineers have faced in the recent past.

That is perhaps the main reason why more and more of his political detractors have reluctantly begun to admit that if there is one politician standing for democracy in today’s Pakistan, it is Nawaz Sharif. They may have been far more vociferous in their support had Sharif’s distant as well as recent political background and tactics not been such a dampener. After all, if he was really serious about muzzling the military’s political ambitions, there was nothing stopping him from taking the entire Parliament along with his newly minted slogan of “respect the vote” while he was in power. There was nothing stopping him from ordering General Raheel Sharif or General Asif Bajwa’s media managers to shut down their twitter accounts – something they turned into a weaponised digital tool against his government – had he managed to convince the country’s political leadership to stand by him as he passed the order. Nothing could have stood in his way had he taken all his foreign policy initiatives to Parliament instead of trying to execute them over wedding kormas at Jati Umra.

Despite the reservations, there is no dearth of support for him leading up to the 2018 general elections, which makes the weeks leading up to the next electoral exercise critical to the future of Pakistan’s struggling democracy. If, in this challengingly short time, he can convince his political contemporaries that he is fighting for the people, the traditional political analysis of the army always getting what it wants, may wither. But if he fails to convince skeptics who argue that he is fighting for little more than a successful transfer of his political mantle to an adoring daughter, a gambit that few may feel compelled to support, including those from within his own party, then the emergence of a democratic Nawaz Sharif may end up meaning little more than the mass delusion Pakistanis enjoyed with the return from exile of a democratic Benazir Bhutto some 32 years ago.

Back to the original question then: does Pakistani democracy really need Nawaz Sharif? The answer may lie in the words of a much-quoted Oriental aphorism: when the finger points to the moon, the idiot looks at the finger. So, whether Pakistani democracy needs Nawaz Sharif or not, it depends on which way he is looking.

No more posts to load