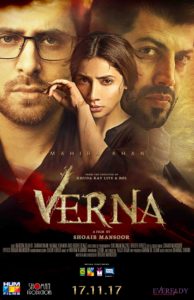

Movie Review : Verna

By Deneb Sumbul | Movies | Published 6 years ago

One would have thought that the country had come a long way since Mukhtaran Mai’s unnerving gang rape in June 2002 that caused a national outcry and made international headlines. But the response to the release of Verna, renowned film maker Shoaib Mansoor’s third film after Khuda kay Liye and Bol, based on the highly sensitive issue of rape, proved that little has changed.

Three days before the movie’s release, a jumpy Central Board of Film Censors (CBFC) decided to ban the film, stating that, “The general plot of the movie revolves around rape, which we consider to be unacceptable.” The subsequent social media furore led the CBFC to give Mansoor 15 days to appeal against their decision — which he did. The film was passed and released on schedule — uncut, but as an adult-rated film. By then it had generated more buzz and whetted people’s curiosity.

Verna drew a wide range of comments, from raves to ridicule. There were those who described it as “a valiant effort,” and then there were those who called it “a cock-and-bull story.” Some saw that it as an awareness-raiser, others questioned its “flawed” ending.

Verna’s plot revolves around the trauma a family goes through following the rape of a family member, and the manner in which the anguished rape victim exacts revenge, after failing to get justice from a flawed legal system that is stacked in favour of the powerful and the privileged.

The film’s opening scene shows a recently married couple, Sara (Mahira Khan), with her polio-disabled husband, Aami (Haroon Shahid), and an unmarried sister-in-law, Mahgul (Naimal Khawar), being accosted while on an outing in Islamabad’s F9 Park, by two armed goons in a black land cruiser that ominously grinds to a halt before them. They make their intentions clear to Aami: they will not leave without one of the two women. They first make a grab for Mahgul, but after a scuffle Sara realises the situation is rapidly turning life-threatening and offers herself in Mahgul’s stead and is taken away.

The plot is reminiscent of a time in Karachi when several forced abductions of women were reported from the city’s Defence and Clifton areas — women travelling in cars, on occasion with their families, were picked up, gang-raped and left on the streets. Verna’s storyline may have also borrowed from a “case of dacoity” in Clifton’s Seaview apartments in which a family gave up the daughter to save a 10-year-old niece from rape. Also, the use of a black SUV in the film took one a few years back, when a Prado with a government number-plate, carrying security personnel, was in the news for accosting women drivers or those travelling alone with their drivers at night.

In the film, Aami is warned against informing the police if he wants his wife to be returned alive, and each and every member of his and Sara’s family are being shadowed to prevent them from filing an FIR. Three days later, barefoot and with her hands bound behind her back, Sara is dropped off near her house.

From then on, the traumatised Sara’s struggle to deal with the troubling reactions of her husband, her parents and in-laws and to seek justice, despite the insurmountable odds, begins.

Sara’s behaviour, her style of dressing, and even her stoic silence over her traumatic experience are called into question. Interestingly, Mahira’s portrayal of a rape survivor was deemed as not being “appropriately miserable” or “distraught enough” by certain critics, mostly male. Audiences in the subcontinent have been fed a steady diet of weepy or hysterical victims in Indian/Pakistani films and television, which has collectively shaped their stereotypical image of a rape victim.

This was precisely the point the film attempted to make — that rape victims do not react in the same manner. Most women recoil into their own shells, while their families, particularly the male members, decide on a course of action or take money from the perpetrators for not pursuing the matter. But there will be those exceptions who, after the initial shock and trauma, would try to process their inner rage. Sara is shown trying to get a grip on herself as she exercises on a treadmill; throwing water at her own reflection in the mirror as if to purify herself and, in a fit of rage, bashing her husband for his terribly hurtful outburst.

An Oxford graduate, Sara is shown as being fiercely independent — she marries a man of her own choosing, a musician who is partially crippled due to polio, against her parents’ wishes; slips past the security cordon of the Punjab governor’s motorcade to confront him for holding up the traffic for hours on end — which leads to her subsequent nightmare. It takes a gutsy woman like Sara to avenge herself, especially since the rapist turns out to be the progeny of a powerful feudal family, with a governor for a father and political connections galore.

Sara’s character also brings to mind the daughter of a very senior Muslim Leaguer who was gang raped in her own home in Karachi’s Defence area in 1991. That gutsy lady did not hesitate to name the culprit behind the crime —¬ a senior minister in the Sindh cabinet and the son-in-law of a former President, who was accused of committing similar excesses against PIA airhostesses. The police lodged her complaint only on the intervention of the then Army Chief, General Asif Nawaz. The case is still pending. Her tormentor roams free.

Verna dwells on the strained relationship between the husband and wife after the horrific offence, providing a glimpse of real life, when many husbands find it difficult to reconcile with the fact of a wife’s rape. Aami is seen pouring through information on a website that explains the initial reaction of husbands and boyfriends to sexual assault on their partners. He is also shown consulting a psychiatrist.

While the film encourages the man to seek counselling, it leaves out the rape survivor from the process, which is very strange since it is the victim who is most in need of counselling. But the fact that Aami finally comes to terms with the tragic incident and returns to support his wife, is one of the positive aspects of the film.

The lead actors, Mahira Khan and Haroon Rashid (making his film debut), were convincing in their roles, given the sensitive nature of the topic. As was Zarrar Khan in the role of Sultan ¬— the suave but sinister antagonist, who gave everyone the chills.

Iran Rehman proved competent in the role of Sara’s lawyer; her segment was critical to the story. She explains the conditions for proving a sexual assault which does not always leave marks, the importance of undergoing a medical test within 24 hours of the rape and the importance of a rape kit; additionally, she speaks of the growing incidence of rape in Pakistan and Bangladesh, specially India, which has recently earned the label of ‘Rape-istan’ for the incredibly high number of rape cases. The lawyer also highlights the reality of marital rape and the silence surrounding it.

Shoaib Mansoor’s films are known to address critical issues and attitudes prevalent in society. His films do not hesitate to tackle the ‘untouchables‘. In a revealing talk show, when a mullah holds forth on how a woman’s attire is responsible for her rape, Sara gives a stinging retort to the cleric: she asks him whether the same holds true for young boys who are being sexually abused in madrassas — a reference to a pervasive and long-standing problem in Pakistan.

Verna’s heart is in the right place. So why did it generate such controversy? One reason could be its subject matter, which makes people uncomfortable. Another could be its ending, which many found inexplicable and perplexing.

In the real world, Mukhtaran Mai did not get justice. Her tormentors were set free, despite the huge outcry in the national, and international media. But in the reel world, Verna’s Sara exacts her own revenge. And perhaps that is what audiences in the ‘real’ world found difficult to digest.

The writer is working with the Newsline as Assistant Editor, she is a documentary filmmaker and activist.