Celluloid Dreams

A sign on the charred remains of Nishat Cinema reads, “Iss bhayanaak hadse ki zimedari kaun uthai ga?” (Who is going to take responsibility for this catastrophe?) On the eve of Ashiq-e-Rasool Day, observed by the government on September 21, 2012, zealous mobs burnt down six cinemas in Karachi, including three prominent ones on M. A Jinnah Road in downtown Saddar in protest against a Youtube video. Ironically, one of those cinemas included Bambino, famously owned by Hakim Ali Zardari, President Zardari’s father, in its heyday. Perhaps, it would not be too much of an exaggeration to say, that the irreverent treatment of the cinemas is a reflection of the general lack of respect for the film industry in our society.

But it wasn’t always so. There was a time when cinema-goers flocked to watch films starring the likes of Nadeem, Waheed Murad, Mohammad Ali, Zeba and Shabnam with soundtracks by Madam Noor Jahan, Ahmad Rushdie and Runa Laila. The 1960s, in particular, were labelled as the ‘Golden Era of Pakistani Cinema’ which thrived under General Ayub Khan’s protectionist policies. The 1965 ban on Indian films certainly helped, but it would be unfair to suggest that that was the only reason crowds thronged to watch these films. Cinema was a meaningful recreational activity for the public, and films were based on social issues with stories audiences could identify with.

Peerzada Salman, Dawn newspaper’s culture critic, explains, “In the ‘60s, the Pakistani directors who were making films had their roots in pre-Partition India. They had their training in the Bombay industry, which meant they mingled with all kinds of creative individuals — men of letters, master technicians and poets such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz who were equally popular in literary circles as they were in the film business. For example, directors like Hasan Tariq and Pervez Malik and the music director Khwaja Khurshid Anwar (whose musical score for the film Koel is in a class of its own), were educated individuals and well-versed in the craft of filmmaking.”

But those days are long gone, and Pakistan has seen many political and social upheavals since, that have undoubtedly left their impact on the film industry. With the separation of East Pakistan in 1971, Pakistani viewers lost Dhaka’s sophisticated production houses. But what proved to be the biggest setback to the film industry was General Zia-ul-Haq’s tenure from 1978 to 1988, with its ruthless censorship policies that stifled all creative forms of expression, including cinema. Since the concept of parallel cinema hadn’t taken root, this gave rise to the Punjabi cinema, which unfortunately tried to replace the ‘middleclass mindset’ with crude agrarianism.” The Lahore-based film industry became synonymous with vulgar dialogues, shoddy camerawork, gratuitous (albeit unrealistic) displays of violence, hyper masculinity and, of course, curvaceous women gyrating suggestively in open fields. Paradoxically, despite the general’s ostensibly puritanical rule, filmgoers witnessed tawdriness and crude sexuality replace the sweet romances of yesteryear. This was, as Peerzada puts it, part of “the intellectual asphyxiation” of the Zia era and just one more aspect of the degradation of the whole system. “Gradually people who didn’t have anything to do with films, in terms of content and how to deal with it, started making films, and this showed in everything from the screenplay to the camerawork to the sound-effects and music quality,” he says.

In 2002, under Musharraf’s more relaxed trade policy with India, Indian films were allowed to play in Pakistan and the empty cinema halls filled up once again. Pakistani film actors and directors protested about the lack of patriotism of the cinema owners and audiences and claimed they could not compete with Indian films as they lacked the funds and resources and had no support from the government.

Now, a new crop of film makers have come forward to challenge these claims.

New Kids On the Block

In 2003, one of the country’s most promising documentary filmmakers, Sabiha Sumar made Khamosh Pani, which played at film festivals around the world and bagged 10 awards for Pakistan, including the Golden Leopard for Best Film. And while Khamosh Pani, which was brilliantly conceived and executed, was making waves across the world and was even being shown in theatres in India, it was not allowed to be screened in Pakistan. Sumar maintains that this was because of the inclusion of an Indian actress, Kiron Kher, in the lead role of a Sikh woman who converts to Islam at the time of Partition to escape persecution. The film also touched upon the sensitive topic of the Islamisation of Pakistan under General Zia-ul-Haq and how it was impacting the youth of the country.

Unlike Khamosh Pani, TV producer Shoaib Mansoor’s debut film, Khuda Ke Liye (KKL) was screened across the country and ran to packed houses. KKL had the backing of the media giant, Geo TV, who ran a massive media blitz. The production was slick and the content provocative by Pakistani standards. Not only was the public watching, but they were also talking about the issues raised in the film: The plight of Pakistanis both in Pakistan and abroad, post 9/11.

There was a buzz about the revival of Pakistani cinema and a few other films were released subsequently, but they were few and far between. Mehreen Jabbar’s Ramchand Pakistani in 2008 on the theme of Pakistanis languishing in Indian jails for mistakenly crossing the border, was one of the noteworthy ones. And then in 2011, Shoaib Mansoor’s next film, Bol, distributed by Geo once again, based on the theme of discrimination against women and transgenders in a patriarchal structure, broke all previous records at the box office and went on to win many international accolades.

But 2013 may be the year that marks the real turning point in Pakistani cinema. This year saw the release of Chambaili locally and Lamha and Josh internationally and awaits other films such as Zinda Bhaag, Good Morning Karachi, Main Hoon Shahid Afridi, Moor, Hijrat and The Extortionist. And anyone who has seen the trailer of Bilal Lashari’s Waar starring Shaan, Ali Azmat, Shamoon Abbasi and Meesha Shafi would be excited to know that the film is finally set to be released this September after three years in the works. Lashari, who studied film-making in California, admits that the delay was due to the many problems an

independent filmmaker faces. He elaborates: “There’s a lack of infrastructure, so filmmakers like myself face a lot of problems — which is why the film took such a long time to be released. But all these films that are being made now are working towards establishing a completely new infrastructure. ”

Nadeem Mandviwalla, owner of Nishat and the world-class Atrium multiplex and a walking encyclopaedia on Pakistani cinema, credits the phenomenon to the opening of new cinema houses in the major cities: “Cinema is rebuilding in Pakistan, so production is more feasible” he says. “As the pie is getting bigger, the returns are getting better.” Atrium, in collaboration with ARY Digital Network, also launched The Platform this May — a space reserved exclusively for Pakistani films. Even Islamabad, which did not have any cinemas except the one owned by NAFDEC once upon a time, will soon have its own multiplex.

Nadeem Mandviwalla, owner of Nishat and the world-class Atrium multiplex and a walking encyclopaedia on Pakistani cinema, credits the phenomenon to the opening of new cinema houses in the major cities: “Cinema is rebuilding in Pakistan, so production is more feasible” he says. “As the pie is getting bigger, the returns are getting better.” Atrium, in collaboration with ARY Digital Network, also launched The Platform this May — a space reserved exclusively for Pakistani films. Even Islamabad, which did not have any cinemas except the one owned by NAFDEC once upon a time, will soon have its own multiplex.

This point is reiterated by Sabiha Sumar who says “Back when Khamosh Pani was released, there was no Cineplex, Atrium or Cinepax.” But now Sumar is set to release Good Morning Karachi (previously titled Rafina) starring Amna Ilyas this year. Although currently in the midst of looking for overseas sales agents for the film, Sumar is hopeful that her latest feature will play in theatres in Pakistan as well.

Many of the new films by a young brand of filmmakers are getting international recognition and winning awards at various film festivals around the world. Most recently, Lamha (titled Seedlings for international audiences) won two awards at the New York City International Film Festival for the Best Feature Film (Audience Choice) and Best Actress in a Lead Role award, which went to the very talented actress and model, Aamina Sheikh. Meher Jaffri, the co-producer of the film along with the Australian Summer Nicks (who can be seen acting in a few of the films coming out this year, including The Extortionist and Main Hoon Shahid Afridi), says, “The film industry in Pakistan is a double-edged sword for young, independent filmmakers. But what is a hindrance for us is also a source of opportunity since the industry is at its nascence.” Despite being accepted into film fesitvals around the world, Lamha could not find an exhibitor in Pakistan.

The actor at work: A screenshot of Mohib Mirza in Lamha.

Perhaps the biggest change we are witnessing is the death of the old formula of films. “A certain standard had been set earlier, and it should have evolved. Yet we never saw that transition, which is why a ‘new cinema’ has sprung up,” says Mandviwalla. He believes that, contrary to the widespread assumption, not only can Pakistani films compete with Indian cinema, but films like KKL and Bol superseded expectations and have thus far been the highest grossing films to grace local cinemas. “Even Shahzad Nawaz’s Chambaili, which targeted a specific kind of audience, did exceptionally well,” he adds.

Jami, speaking to Newsline from Bangkok where he is working on the post-production of his debut feature film Moor (Mother), attributes the sudden burst of films to two factors: the introduction of digital cameras and high-end technology, and a generation of educated professionals who are tired of substandard films and want to produce quality work. They have taken things into their own hands instead of waiting for a cue from someone else, least of all from the government. (“What government?” he asks. “They still think the cinema industry is a red light district!”)

Jami is particularly critical of Lollywood and glad to witness its demise. “Lollywood should either take a back seat or produce better quality films.”

“Rather than actors we were looking for specific personalities — Khaldi, Taambi and Chitta. Since the three main ‘leads’ had never acted before, a long process of workshops followed, one of which was conducted by the acclaimed actor Naseeruddin Shah (who plays Puhlwan in the film). This process of work on the script and actors has led to the film having a very ‘intimate’ feel; we believe that the audiences will closely relate to the characters and events on screen.”

But not everyone shares the same views. The writer/director duo of Meenu Gaur and Farjad Nabi credit Lollywood as the inspiration behind their film, Zinda Bhaag. Gaur says, “We envisioned Zinda Bhaag as a sort of bridge between the old and the new. Given the near collapse of what used to be an extremely vibrant film industry, and the fact that both Farjad and I are big fans of our cinema, we wanted to reference that cinema in our film while simultaneously telling an absolutely new story in an altogether different form to that of a traditional film. Our motivation for having the traditional hand-painted poster for Zinda Bhaag is also a paean to the erstwhile Pakistan film industry, as is the music in the film.”

Many of the new breed of filmmakers are not connected to any major production houses and some are first-time directors, hence they are not afraid to be more experimental. What they lack in resources and sometimes experience, they make up for in enthusiasm — and if they’re lucky, they will find distributors who are equally enthusiastic to back their films.

Furthermore, many of these new, independent films are often — consciously or not — politically charged and tend to have strong social themes. Thankfully, we are also witnessing the introduction of more complex and realistic characters in these films, instead of black and white portrayals. The protagonists are often ordinary people living in absurd times, and forced by fate to act in extraordinary ways.

keep on truckin: Actors from Main Hoon Shahid Afridi in a lighter mode.

For example, Lashari states that Waar is an action film that should be enjoyed as such. But at the same time, it is a film about terrorism, and specifically centred around the attack on the police headquarters in Lahore, which forms the backdrop to the story. Although Lashari claims that he does not want his film to come across as “preachy,” he does expect audiences to start talking about some of the issues raised in the film.

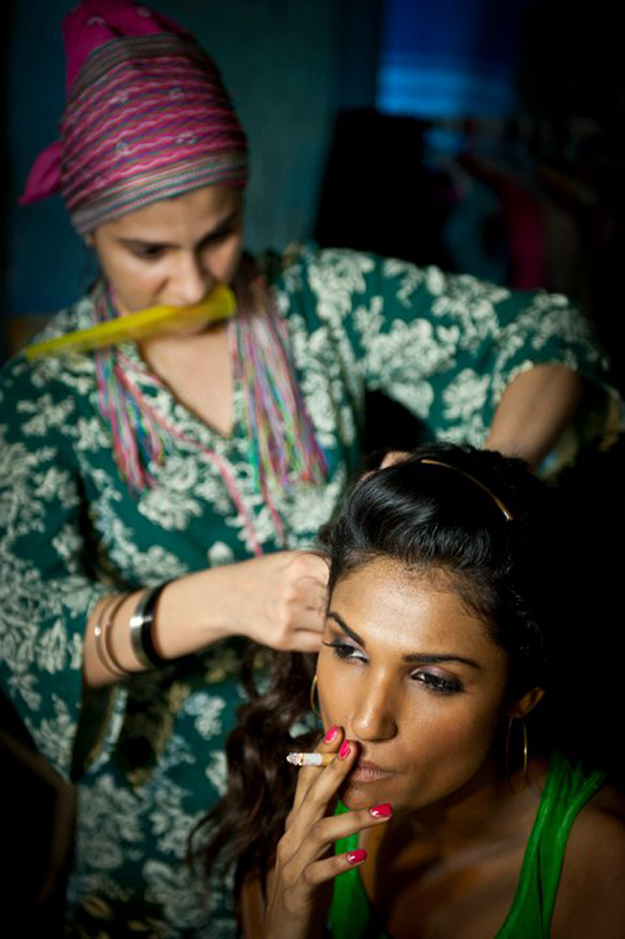

Even Sabiha Sumar’s Good Morning Karachi, a coming-of-age film about a lower middle class girl entering the cut-throat world of fashion, includes the violence and politics of the city as a backdrop. “The film is as much about the city as it is about the girl in it,” says Sumar.

And Moor, set in Northern Pakistan, is about how women take charge of families as men crumble under pressure. Jami says, “At its core, the film is really just about how to live honestly in these difficult times. When almost every pillar of our country is about to collapse, Moor is about standing up again and doing the right thing under extreme pressure.”

On the other hand, Zinda Bhaag is set in Lahore and takes us into a sub-culture of the city and revolves around an ordinary street. Gaur says that the premise of the film is “neither exotic nor filled with terror — it’s just the everyday comic and tragic stuff lives are made of. We wanted the audiences to experience the story as we had experienced it —the story of our friend, our cousin, and our neighbour.” With this in mind, the directors chose ordinary men with no prior acting experience as the main leads. “Rather than actors we were looking for specific personalities — Khaldi, Taambi and Chitta. Since the three main ‘leads’ had never acted before, a long process of workshops followed, one of which was conducted by the acclaimed actor Naseeruddin Shah (who plays Puhlwan in the film). This process of work on the script and actors has led to the film having a very ‘intimate’ feel; we believe that the audiences will closely relate to the characters and events on screen.”

Along with Zinda Bhaag and Iram Parveen Bilal’s Josh, another film to be released this Eid is the massive Main Hoon Shahid Afridi (MHSA), directed by Syed Ali Raza and produced by Humayun Saeed and Shahzad Nasib. Saeed also stars in the film alongside veterans Nadeem Baig and Javed Sheikh, as well as Mahnoor Baloch and Noman Habib (who plays the lead role) and a host of other familiar faces from television who are making their debut on the big screen.

Saeed is not a newcomer to films, having starred in Javed Sheikh’s Khullay Aasmaan Ke Neeche amongst others, but MHSA is the first film he has produced.

Speaking to Newsline on the phone, the very hardworking (and somewhat sleep-deprived) actor/producer — who is currently working with Mahira Khan on another feature-length film by Momina Duraid, scheduled to be released next year — sounded as anxious about the film’s release as he was excited. Saeed mentioned that the response so far from people who have seen the film has been overwhelmingly positive. But, he adds, “Jitna acha response screening pe milta hai, utna ziyada darr release pe.”

The film, along with Waar, is possibly the most anticipated of all the new films to be released this year; partially because it includes such a high-profile cast, but mainly because the film is about a national passion: Cricket. Sports-films may be common in Hollywood and Bollywood, but this is first Pakistani film of the genre. Saeed makes it clear that his film is purely commercial, unlike most of the other independent films being released this year, with a larger audience in mind. Consequently, the film includes a generous dose of song, dance and glamour. Rather than giving a message or tackling difficult social themes (“main intellectual nahin hoon,” he says lightheartedly), MHSA’s focus is solely on one thing: To entertain the Pakistani masses — sort of like what Afridi, the cricketer the film’s title pays tribute to, does in every match.

It may be too early to call these revolutionary times in Pakistani cinema, but a change is coming — and that change promises to be exciting.

The writer is a journalist and former assistant editor at Newsline.