Pilgrimage to Perdition.

By Ali Arqam | Newsbeat National | Published 7 years ago

Shiite faithful pilgrims gather between the holy shrine of Imam Hussein and the holy shrine of Imam Abbas, in the background

Spiritual journeys to revered sites in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria and Iran are a ritual that has been observed by Muslims for centuries. In recent years, however, the rise in sectarian tensions across the region, including Pakistan, have imperilled these journeys for the Shia Muslims in particular. In the past, militants targeted kafilas of zaireens (pilgrims) that made their way to Iran through Balochistan. Now, the ongoing war in Syria, has created new risks for pilgrims. Upon their return to their homes in Karachi, Quetta, or Kurram Agency, they suddenly disappear or face detention, and are held under suspicion of taking part in the war in Syria.

The month of Ramazan marks a significant increase in the number of Pakistanis travelling to Saudi Arabia and Iran on spiritual sojourns. Saudi Arabia is home to holy sites in the cities of Mecca and Madina, and attracts Muslims from across the globe to perform Hajj or Umrah at these revered locations. Every year, more than two million pilgrims, from 188 countries, perform Hajj, while six million perform Umrah. Ten per cent (approximately 145,000) of the people who visit Saudi Arabia for Hajj are Pakistanis, while the number of Umrah pilgrims from Pakistan amounts to 16 per cent (approximately 1.2 million).

The Umrah season, which starts in the month of Safar (the 2nd month of the Islamic lunar year) and finishes with the end of Ramazan, has witnessed 5.7 million pilgrims in the last nine months, according to statistics in an official Saudi publication. These numbers are expected to exceed 6 million, owing to a significant increase in the number of visitors performing Umrah in the month of Ramazan. In Ramazan, performing Umrah is accompanied by participation in taraweeh prayers and the Khatm-e-Quran, as well as special prayers on the 27th day of Ramazan.

Shia Muslims also travel to Iran and Iraq to visit the sites held sacred in the Shia faith, mostly the tombs of Imams, or to participate in various events, such as the annual gathering at Karbala for the observance of Ashura (9th and 10th of Muharram, the 1st month of the Islamic lunar year), the religious ritual that commemorates the death of Imam Hussain — the grandson of Prophet Mohammad (PBUH) — and his companions, in the early Islamic era, or the Chehlum (referred to in Arabic as Arbaeen, or the 40th day), which marks the end of the 40 days of mourning following Ashura. There are also those who spend the last 10 days of Ramazan either at Karbala, or Najaf in Iraq, or Mashhad in Iran.

The flag of the Zeynabiyoun

Trips to Iraq have witnessed a surge, especially in the post-Saddam Hussein era. Hussein had imposed restrictions, owing to internal rifts and the decade-long war with Iran. When the sites were reopened to travellers from across the world, they started attracting people from a variety of countries. The annual Arbaeen procession in Karbala, Iraq, has turned into the largest Shia gathering in the world. The number of visitors exceeds a million. Visitors from Pakistan, however, still prefer to remain in Iran due to the security situation in Iraq.

According to Tauqeer Zaidi, a Karachi-based software engineer, “Pakistani zaireens (pilgrims) have been visiting sacred sites in Iran, Iraq, and Syria.” Zaidi explains that now, Syria has been dropped from the list due to the ongoing war. “Tour operators have had to offer 10 to 18 days packages with charges varying from USD 800 to 1,250,” he continues. “You have to choose one of the itineraries, either to Iran or Iraq, or to both. The tour operators make all the arrangements, such as air tickets and visas of both countries, as well as hotel reservations. Some of the tour operators have their own hotels there.”

Zaidi points out that kafilas (caravans) of the zaireens comprise hundreds of members. “Our kafila, on our February tour, had 600 people, who were divided in two groups,” he explains. “The tour to Iran included visits to Qum, Tehran, Mashhad, and Nishapur, while in Iraq we went to Najaf, Karbala, Samarra, and Kazmain. We were under tight security throughout. The operators were very cautious about the movement and activities of the individuals, and constantly kept an eye on all the members, and withheld their travel documents, so no one could stay behind.”

Umrah visas to Saudi Arabia or ziarat visas for Iran have also been used as tools by human traffickers. Many people who enter Saudi Arabia on Umrah visas, stay on for work. In the case of Iran, traffickers use either the ziarat visas, or the 900-kilometre-long Pakistan-Iran border.

According to ForwardKeys, an organisation that provides data on air traffic patterns, the number of Pakistani citizens travelling to Iran in 2016 was 74 per cent higher than that in 2015. Only five per cent of them travelled for business purposes. This clearly indicates that most of them visited as religious tourists.

The figures issued by the Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) last month, suggest a significant rise in the numbers of Pakistani nationals who were intercepted by Iran in an attempt to enter Europe via the Iran-Turkey-Greece route. In 2016, Iran handed over 29,074 Pakistani nationals to the authorities in Taftan, at the Pakistan-Afghan border. These figures were 11 per cent higher than those in 2015. Furthermore, 8,512 Pakistani nationals were intercepted by Pakistan border forces on the Pakistan-Iran border, in 2016.

“More than 30,000 people from Kurram Agency are currently in Iran, working petty jobs,” claims a political activist from Kurram Agency. “They stayed on illegally after their ziarat visas expired. They work as unskilled construction workers until they are apprehended and expelled, or they find an opportunity to enter Europe through the Iran-Turkey border.

“It is very risky,” explains the activist, “as there are incidents of people getting killed from firing by the border forces. Also, the recent immigrant crisis in Europe has made it almost impossible for them to move there.”

Mohsin Jaffery, a student of Karachi University who hails from Muzaffargarh, said that one of his relatives, a young boy of 22 years, went to Iran in 2014. Subsequently, he moved to Iraq, where he works at a hotel in Kazmain, earns USD 400 per month and sends some money back home. Jaffery explains that he doesn’t know how to return, as he hardly has any documents left with him. “There are dozens of young boys from different parts of Sindh and Southern Punjab, who are working in those hotels around the shrines and pilgrimage sites,” explains Jaffery.

Quetta : Security men gather at the site of a suicide bombing in Quetta,

“Tour operators have to face fines and cancellation of licenses if any of the zaireens leave the group and don’t return,” complains a tour operator from Gulistan-e-Johar. “That is why they have to take great care. Recently, people were picked up by the law enforcement agencies upon their return from ziarats of Iran or Iraq, as the agencies suspect some may have gone there to participate in the war in Syria,” he continues. The tour operator points out that although many cases are reported in Karachi and in other districts of Sindh, people hesitate to be vocal about them, as they fear there will be repercussions for their families.

An activist from the ethnic Hazara community in Quetta, referred to two such incidents. The first is that of Mobarak Ali, a 60-year-old retired police official from the Loralai district. Ali, who works as a tour operator, was detained a few months back. His family was told that he was being investigated on the suspicion of assisting people who were going to participate in the Syrian war. They are assured that he would be released if proven innocent. The second incident, according to the activist, is that of a young man from Hazara Town, Quetta, who has “been missing for the last four months after he posted pictures of his religious tour. It has been alleged that some of the pictures were from sacred sites in Syria.”

A law enforcement official, providing insight on the arrests and detentions from different parts of Karachi, revealed, “Those detained by the law enforcement agencies are involved in political or sectarian violence in Karachi, or other criminal activities, and were hiding to avoid arrest.” He explains that the arrest of these individuals, upon their return from Iran or Iraq, did not necessarily mean that law enforcement agencies suspected them of participating in the war in Syria. “Though,” he was quick to add, “in some cases, chances of fighting in Syria could not be ruled out. Those who have fought there could resort to sectarian violence here in Karachi.”

At the start of this year, the National Counter Terrorism Authority (NACTA) included another name in its list of banned organisations. It was that of a lesser-known militant organisation called Ansar-ul-Hussain. It has a presence on social networking sites, was engaged in activities in Karachi and Kurram Agency, and was alleged to have recruited Shias to fight against IS in Syria and Iraq, and to protect sacred sites.

Since 2015, national and international publications have reported that a group of Pakistani Shias by the name of ‘Zeynabiyoun,’ are fighting against IS in Syria, alongside other Shia militant outfits. A picture reveals that the group’s flag has ‘Farzandan-e-Shaheed Arif Hussaini’ (scions of Shaheed Arif Hussaini, the Shia cleric from Kurram Agency, who was killed during the Zia era) written on it.

In the recent terrorists attacks in Kurram Agency, the militants who claimed responsibility also accused the people of Parachinar, in Kurram Agency, of fighting against affiliate groups of IS and Al-Qaeda in Syria.

A Karachi-based academic and social activist believes, “Most of these suspicions of Shia activists’ involvement in the Syrian war have no concrete evidence, and are based on unsubstantiated claims and propaganda on the Internet and social networking sites.” The academic points out that several Shia detainees had later been released, and argues that had there been the slightest evidence of their complicity, they would have faced a very different fate. On the other hand, the whereabouts of Shia activists picked up from different cities after Ashura last year, he says, are still unknown.

In the light of recent forced disappearances, there is an element of despair in the families, as people hesitated in taking to the streets to support them. A protest call in Karachi was not met with an enthusiastic response. Only the families — the mothers and the siblings — of the missing persons showed up, and human rights activist Asad Butt, along with a few others, stood with them.

The irony is, the Shia religious leadership has not come forward either. A relative of one missing Shia boy recalls his meeting with an influential Shia cleric in Karachi, who after hearing the entire story said, “We are going through terrible times, just pray to God that these times pass.”

(Identities of individuals have been withheld or changed for safety reasons).

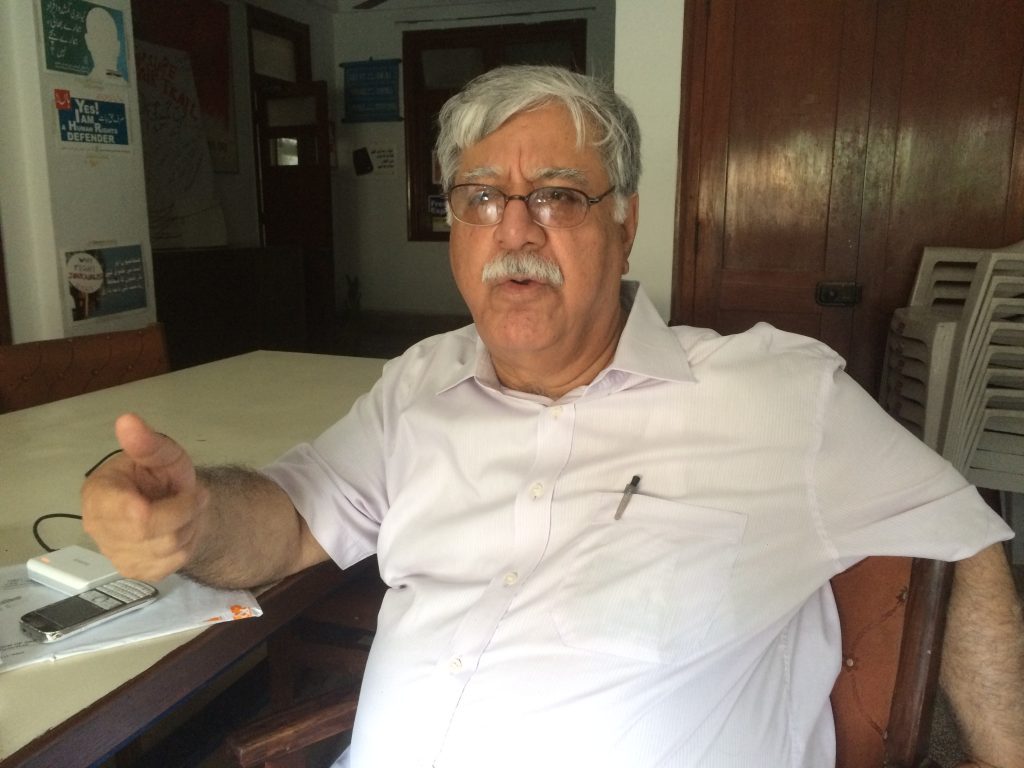

“Most Shia boys were picked up upon their return from Iraq.” – Asad Butt

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) has, in their annual report, ‘State of Human Rights in 2016,’ noted that, among other human rights violations, in the year 2016, 728 Pakistanis were added to the ‘missing persons’ list — the highest number in the last six years.

Asad Butt, the Vice Chairperson of the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan in Sindh, tells Newsline that, “Among other cases of enforced disappearances, most of the Shia boys, from Karachi and other cities, were picked up upon their return from Iraq. They are suspected of having taken part in the Syrian war, despite the fact that their passports have not shown entry to the troubled country.” According to Butt, it has been noted that “in other cases of disappearances, men in plain clothes, who drove vehicles without registration number plates, were involved. But in the case of many Shia zaireen (pilgrims), uniformed police officials, the SSP, or the local SHO, or Rangers personnel, had come to make the arrests, but when the families approached the courts, the law enforcement officials refused to admit that they had picked them up. The families were assured, unofficially, that those detained would return after the investigations, but none of these assurances have been followed up on.”

Commenting on the role of the HRCP, Butt argued, “The problem in these cases is, that while the family members approach us [for help], but they decline HRCP bids to document these incidents. They are either scared about their own safety, or they think making it public could threaten the lives of those who have gone missing.” When asked about the number of Shia boys who have gone missing, he recalls, “there are six to seven cases that were reported from Karachi. Two boys from Naushehro Feroze were picked up; one was released, and the other is still missing. With the exception of Naeem Haider from Naya Golimar, the details of the rest have not been provided to the HRCP.”

Speaking on the overall scenario of the increase in enforced disappearances during the past year, Butt says, “You cannot respond to dissent with such acts. If the Baloch or Sindhis speak out for their rights, demand a just share in resources, you have to deal with it politically. If the law enforcement authorities themselves treat the law and the institutions with disregard, how can they expect others to abide by these laws; it will lead to anarchy.”

Butt emphasises, “Irrespective of the activities these boys were involved in, whether they go to these sacred places for work or military training, or to fight, or anything else, what we demand is that the law enforcement agencies and security institutions should not flout the laws of the land. Just produce these persons in courts of law, charge them, gather evidence, and let the court decide.”

Ali Arqam main domain is Karachi: Its politics, security and law and order