Of Life and Death Sentences: Why We Should be Sympathetic

By Natasha Japanwala | Opinion | Viewpoint | Published 13 years ago

Though I have no personal idea of what someone on death row looks like, my mother’s obsession with silver-screen crime thrillers has given me a caricaturised concept: bloodshot eyes, fixed sadistic grins and always some kind of obsessive-compulsive trait. These characteristics belong to loners: people who are ostracised or people who have ostracised themselves. The kind of person I’ve always imagined on death row commits a series of crimes. Time and time again this person kidnaps innocent individuals, tortures, stabs, mutilates them. This type of serial killer throws their victim’s remains into a disposal bag and tosses it into a nearby stream, feeling little or no remorse.

Though I have no personal idea of what someone on death row looks like, my mother’s obsession with silver-screen crime thrillers has given me a caricaturised concept: bloodshot eyes, fixed sadistic grins and always some kind of obsessive-compulsive trait. These characteristics belong to loners: people who are ostracised or people who have ostracised themselves. The kind of person I’ve always imagined on death row commits a series of crimes. Time and time again this person kidnaps innocent individuals, tortures, stabs, mutilates them. This type of serial killer throws their victim’s remains into a disposal bag and tosses it into a nearby stream, feeling little or no remorse.

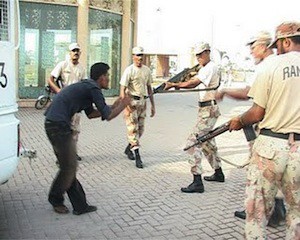

Yesterday, for the second time, my stereotypical image of someone on death row was challenged. Growing up, rangers along with their military camouflage and long rifles were never threatening. Despite their stern expressions, they seemed like they were doing their job: protecting Karachi and its citizens. Perhaps that is why I was as shocked as I was when I watched the video of Sarfaraz Shah being shot and then ignored as he subsequently bled to death.

It wasn’t the first time those employed to enforce the law in this country abused it. Corruption is everywhere, and the law, indeed justice, is nowhere to be found because of it. However, it seems to me that our law enforcers are not violence-loving, cold-blooded killers. There’s more to it. Our law enforcers do try to do their job, the problem is that the manner in which they do it is terribly flawed. A gross misinterpretation of what their job entails, coupled with a skewed understanding of both this society, it’s “conventions” and the “law” (as showed by the recent incident in Lahore where police assaulted the female curator of the Nairang Art Gallery), have led them to behave in unthinkable ways. The Pakistan Ranger incident and the death of Sarfaraz Shah serve as an example of this. They had neither the authority nor the power to do what they did; they did it anyway. A big problem with Pakistan’s law enforcers is simply that they think they have the right to do things they don’t have any right at all to do.

Those men may well have thought they did the correct thing by shooting a young boy for a petty crime they were not at all sure he had committed. Perhaps they felt there was no need to wait for any further evidence; in the moment, they thought they knew enough. Is this lack of procedure not something we see everywhere, in the way an overwhelming number of systems run in Pakistan? I refuse to justify what they did by suggesting they were not familiar with logical, necessary protocol, for nothing this young boy could have done would justify what was done to him. However, my point is that we need to consider not what the Rangers did, but what they thought they were doing. Here is something to think about: how far can you blame someone for their action, if their intentions were not half as bad as what they did? And how far can you blame someone for terrible intentions if they do not understand these intentions are terrible to begin with?

And then there’s the impact of the moment. Yes, that one ranger on death row may have misunderstood the situation, or had the incorrect intentions. But what about the others? Standing by and watching someone die, heartless as it is, is something psychologists explain by what is called the bystander effect: when an individual does not offer any help to a victim in an emergency situation where other people are present. Given this social-psychological phenomenon, it is possible to remove some of the blame placed on the shoulders of the six rangers who have been given life imprisonment; since none of the six were acting to save a bleeding Sarfaraz Shah, they all inferred that help was not needed.

Life imprisonment for inaction alone doesn’t seem right to me at all. Maybe it’s because of the thousand more crimes that go unrecorded and unnoticed, the thousand more cases that are half-heartedly investigated and quietly dropped, the thousand more criminals who get away with brutal murder without so much as a warning. If I started hyperlinking examples of the aforementioned, I would never be able to stop. There are far too many of them, glaring from the front page of every newspaper in this country.

I have spent much time and many words trying to defend these seven men, though I don’t sympathise with them half as much as I sympathise with whom they shot and left to die. The truth, however, is that I am vehemently against both capital punishment and life imprisonment.

These forms of punishment exemplify to me the road often left untaken: that of true education. For education, here, is not of the examination and textbook kind. It is instead constructed of thought, empathy and morality; a keen awareness of the world that surrounds us and the people that inhabit it. This kind of education should be entirely innate, but like most hereditary traits it is how this innate education interacts with what our environments throw at us that really make a person. Maybe these seven rangers grew up in communities where violence was always around the corner, or in homes where domestic abuse was the norm. Maybe they never got the kind of education we should all be getting, and maybe this robbed them of basic humanity.

Perhaps I should explain what exactly I mean when I suggest education is a necessary alternative to incarceration. I am not campaigning for prisons to be abolished. No, I am just campaigning for their reform. For a third-world country such as ours, reforming prisons is not a priority. However, prisons should function as communities where there is ample access to educational classes and recreational activities that are designed to reform inmates. Sentences should be shortened and regarded as rehab-time rather than jail-time. A system like this one would not only give inmates a chance to think about what they have done wrong but also a chance to want to lead a better life, and ultimately a chance to want to be a better person. I am well aware that the seven rangers will never see a prison like the one I have described. No matter. Let’s just ask what if?

What if these men were given a chance at reform, a chance at learning, perhaps for the very first time, what empathy is. They certainly didn’t know of it the day they killed Sarfaraz Shah, and they may still not know of it now. If the loss of an innate sense of empathy is something that can be blamed on the environments we are raised in, or the environments we work in, then these seven men retain the right to have made a mistake.

In my opinion, punishments do little for mistakes outside of breeding further bitterness and hatred.

If these seven men were given a shot at reform, at a real education, they may learn that what they did was grossly inhuman. This is the only way they can really regret what they’ve done. The only way they can understand it. For there is no point in all of us trying to understand those moments captured on film if they don’t do so as well.