Memories of Another Day

By Peter W. Galbraith | Special Report | Published 7 years ago

Peter W. Galbraith is a former US Ambassador to Croatia and former United Nations Assistant Secretary General. He was awarded the Sitara-i-Quaid-i-Azam in 1989 for his support for human rights and the restoration of democracy in Pakistan.

My association with Pakistan began with one famous and glamorous woman and revolved around another. As an 11-year-old in 1962, I accompanied Jackie Kennedy on her flight from New Delhi to Lahore. My father was Kennedy’s ambassador to India and had just organised Mrs Kennedy’s highly successful trip around the country. In those days, no US official — and certainly not the wife of the president — could visit neutral India without also visiting America’s ally Pakistan. Mrs Kennedy asked my father to join her on the Pakistan leg of the trip and I got to tag along.

Field Marshal Ayub Khan hosted Mrs Kennedy and her party at the Lahore horse and cattle show. I remember the extraordinary precision of the Pakistani cavalry as they speared tiny tent pegs with a long lance at a full gallop. One of the children present at the event was Benazir Bhutto, the daughter of a dynamic young Pakistani cabinet minister. Neither of us remembers meeting the other then, but seven years later we entered the same Harvard class and became lifelong friends.

Benazir and I spent four years at Harvard (where she introduced me to the woman who became my first wife), followed by another two at Oxford. She was also at my family home in Vermont for my birthday on New Year’s Eve, 1971. In the guest book, she wrote that she would always remember the occasion as the 21st birthday of the future US president. She planned to be a diplomat. Ironically, it was she who went on to be the politician who rose to the top, while I became the diplomat.

In 1979, I joined the staff of the US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, where my portfolio included the Indian subcontinent. Pakistan was at the centre of the Committee’s consideration — over nuclear proliferation, human rights and Afghanistan. I became embroiled in some of the most controversial issues in US-Pakistan relations.

I arrived at the Committee just one month after General Zia-ul-Haq had executed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. Many senators had appealed for Bhutto’s life — I had mobilised some of them — and the hanging left bitter feelings toward Pakistan’s brutal military dictator. At about the same time, the Carter Administration cut off US assistance to Pakistan, because of its nuclear programme. US-Pakistan relations could not have been worse.

Yet, by the end of the year, Pakistan’s stock was rising in the US. On the day after Christmas, the Soviet Union overthrew and murdered Afghanistan’s communist president and sent in troops. Although we know now that the Soviet invasion was the defensive action of a sclerotic leadership in Moscow, the Carter Administration and much of the American foreign policy establishment saw the invasion as an expansionist move and possibly the first step in the long-held Soviet drive for a warm water port. (I sometimes wondered whether some of the Cold War hawks had ever noticed that Afghanistan is landlocked). Pakistan became a frontline star and Carter offered weapons and an aid package.

Zia — perhaps with an eye to Carter’s background as a peanut farmer — derisively dismissed the US offer of $200 million as “peanuts.” But when Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the new Administration offered Pakistan $3.2 billion and the sale of American F-16s. In order to become law, the administration needed Congress to repeal US non-proliferation laws as applied to Pakistan and for Congress to authorise the money.

I opposed the aid package for many reasons. I was concerned that the arms package — and in particular the F-16s — were far more likely to be used against India than to deter the Soviet Union. I thought US assistance should be used to leverage on non-proliferation goals in South Asia. But, most of all, I did not believe the US should be helping a brutal military dictator. And, part of it was personal.

In March 1981, Zia used the hijacking of a PIA plane to Kabul — which Benazir’s brothers had foolishly embraced — as the pretext to throw Benazir and her mother in prison. While Begum Bhutto was confined in Karachi central prison, Benazir was thrown into a ‘Class-C’ cell in the Sindh desert. I was afraid that Zia intended to kill her and I thought the leverage of US assistance provided a way to stop him.

When the foreign assistance bill came up, I persuaded Senator Claiborne Pell to attach an amendment linking the US assistance to respect for human rights and the restoration of representative government. This was a largely symbolic step, but it began a three-year campaign in the Senate that linked US assistance and arms sales to Benazir’s release and freedom for the other political prisoners.

One of Pakistan’s most regular visitors to Washington was Sahabzada Yaqub Khan, the elegant and thoughtful Foreign Minister, who had many friends in the Senate from the time he was Ambassador in Washington. At each meeting, Senator Pell — sometimes joined by Committee Chairman Charles Percy — raised the issue of Benazir’s imprisonment. Yaqub Khan, who later became a friend, was clearly embarrassed by his own government’s treatment of a young woman and, I have no doubt, pushed for her release.

In December 1982, General Zia-ul-Haq made a state visit to Washington and, of course, came for lunch with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. He showed up early and the only two people at the Committee’s ornate Capitol Office were Senator Pell and myself — his two biggest critics! After a few minutes of polite conversation, he asked if he could pray and we escorted him to Senator Pell’s nearby private office.

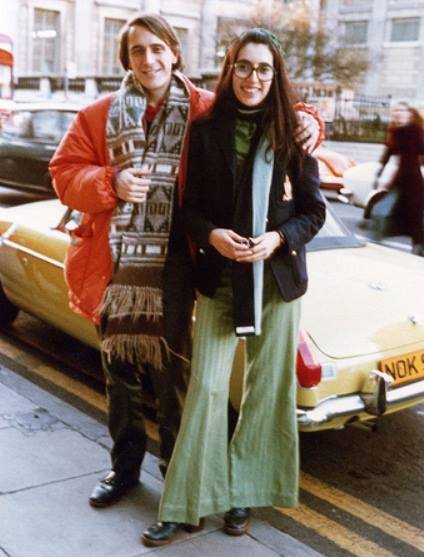

Peter Galbraith with Benazir Bhutto.

The lunch was not so amiable. Senator Pell began the questioning by handing him a letter that I had written about 11 political prisoners, several of whom faced death sentences. And, of course, the first name was Benazir Bhutto. When Pell raised her case, Zia, who was fully prepared for the question but nonetheless became agitated, asserted that she now lived in a better house than any senator, that she had use of the phone and that friends could visit. There was some truth to the first statement. Just before the Zia visit, Benazir had been moved from prison to house arrest in the family home at 70 Clifton. The rest was a lie, as I learnt when I tried to call her shortly after the lunch broke up.

Nonetheless, the statement gave us valuable leverage. For the next year, senators pushed Yaqub Khan and the Pakistani ambassador to permit me — indisputably a friend — to visit her. Finally, in January 1984 — hours after I arrived in Karachi to try to see her under house arrest — Benazir was put on a plane out of the country.

Zia’s 1982 visit had another consequence: the so-called Pressler Amendment. Speaking to a joint meeting of the Congress, Zia declared “Pakistan has neither the means nor the intention of developing a nuclear explosive device.” This was, of course, a lie, since Pakistan had an active nuclear programme. However, I decided that Zia should be held to his word. When the next foreign aid bill came up, I wrote an amendment for Senators Glenn and Cranston that cut off arms sales and most assistance unless the US president certified that Pakistan did not possess a nuclear explosive device, was not developing a nuclear explosive device and was not in the process of acquiring material for such a device. The Committee initially adopted the amendment unanimously, with all the senators saying that Zia should be held to his promise. The Reagan Administration, however, believed the Cranston-Glenn Amendment would lead to an immediate cut-off of aid and persuaded the Committee to adopt instead (by one vote) Senator Pressler’s Amendment that only required the president to certify that Pakistan did not have a bomb. In the context, Pressler’s Amendment was pro-Pakistan and successfully preserved US aid to a deceitful military dictator. Years later, Pressler and others presented it as an effort to cut off arms sales that might threaten India. In 1996, Indian-Americans contributed a quarter of the funds Pressler raised in his unsuccessful re-election bid in South Dakota.

In August 1988, Zia died in a plane crash, thus opening the door for the restoration of democracy. I was an observer at the November 1988 elections. Benazir invited me to join her for the last day of the campaign and I spent election night in Larkana with her and her new husband, Asif Zardari, as the returns came in.

It is hard to recapture in words the excitement of those days. In Benazir’s Larkana constituency, even the cows were decorated with the PPP arrow. And, outside the Bhutto compound, journalists from all over the world — including the BBC, Deutsche Welle, and the three American networks, waited. I made a small contribution to the process. The next day, the preliminary results showed the PPP with 90 seats, short of a majority, but well higher than the runner-up, the Pakistan Muslim League. Benazir’s press team prepared a statement alleging fraud in the Punjab. Benazir asked me what I thought of the statement. I suggested that she forget about the vote-rigging and instead tell the world that she had won. At her request, I drafted a short victory statement. The world media now had the story they wanted: after 11 years of hardship and struggle, a beautiful and courageous 35-year-old had just been elected the first female to lead an Islamic country. Pakistan’s interim President (Ghulam Ishaq Khan), who wanted anyone but Benazir (he even asked her mother to be prime minister), had no choice but to ask her to form the government.

I have no doubt that Benazir’s election on November 16, 1988, was the high point of her public life. Enduring the hanging of her father, years of imprisonment, and the hostility of Pakistan’s military and intelligence services, she had prevailed electorally and in so doing had restored democracy. While she had achievements in two truncated terms as prime minister, she was also unable to accomplish much of what she had set out to do.

My association with Pakistan continued for another two decades beyond those halcyon days. While still with the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, I made four extended trips to the country during Benazir’s first term, including carrying a private message from her to the Indian Prime Minister, Rajiv Gandhi.

The Pakistani military took advantage of her ouster in 1990 to advance Pakistan’s nuclear programme, so that President Bush could no longer make the certification required by the Pressler Amendment. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the chairman of the South Asia Subcommittee and a former Ambassador to India, and I, met with Deputy Secretary of State, Larry Eagleburger, to persuade the Administration nonetheless to make the necessary certification (I was concerned that India would read our failure to certify as US intelligence community judgement that Pakistan has nuclear weapons that, in turn, could set off a nuclear weapons race in South Asia). Alas, I was unable to persuade the Bush Administration to ignore a law that I had initiated, albeit in very different circumstances.

Many Americans see Pakistan as a failed state. I do not. Pakistan has had a complicated path to democracy but it is hard to see a return to the brutal type of military rule of Zia-ul-Haq, or even the more moderate form represented by Pervez Musharraf. Pakistan’s civilian leaders — whether it is Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif or President Asif Ali Zardari — have a shared interest in a military that respects civilian leadership. It has now been 45 years since India and Pakistan fought a full-scale war and another one is increasingly unlikely (although there is always a danger that a terrorist incident could escalate). Extremism, sectarianism and terrorism are a challenge for Pakistan but the news reporting focused on these issues often misses the existence of a vibrant economy, a growing middle class, and strong professional capabilities.

Pakistan-US relations have also changed in the years that I have been involved in them. In the 1980s (and to a lesser extent, under Musharraf after 9/11), Pakistan was dependent militarily, economically and psychologically on the United States. In fact, the psychological deference to America probably far exceeded any actual power that the United States wielded. One consequence was growing anti-American sentiment in Pakistan. A more confident democratic Pakistan should be less dependent on the US in substance as well as psychologically. I hope this leads to a friendship of equals, which should be more durable than our past relations.