Long Day’s Journey into Light

By Afsheen Ahmed | Bookmark | Published 6 years ago

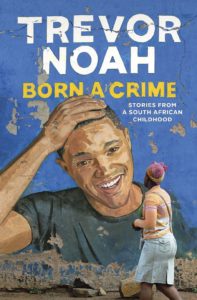

Born in the dying years of apartheid in 1984 in Johannesburg, South Africa, to a black mother and a Swiss/German father, when any sexual relationship between a black and white person was still a criminal offence, and punishable by imprisonment, Trevor Noah’s birth was, technically, a crime. Not until Nelson Mandela was released six years later on February 11, 1990, could the light-skinned Trevor and his mother move about freely together. And, of course, there was no way the three of them could have been seen together as a family in public, even though Trevor’s Swiss father acknowledged him and wanted to be involved in his life. The repercussions would have been too great. Sounds medieval, but it was only 30 years ago.

So starts the amazing, frequently violent, mostly poverty-stricken account of Trevor’s childhood. Now, at 33, Trevor Noah is the host of the award-winning ‘The Daily Show,’ succeeding the inimitable Jon Stewart in 2015. How he got there is another book; this biography details the story of his childhood and teenage years in South Africa. A Mother’s Day gift from my son this year, I realised how appropriate it was: the book is, primarily, a tribute to a mother from her son.

Along with Trevor’s story, it is an insider account of what apartheid meant, how it impacted the people who lived under this barbaric regime, the planned destruction of a race and a civilisation to serve the interests of a privileged few — the white race.

Born a Crime is a fast-paced, action-packed read. And, sometimes, since it’s written in such a matter-of-fact manner, you don’t immediately comprehend the horror. How apartheid was implemented, the colonialists’ methodology of ‘divide and rule’: a separate language for each tribe so that there would be minimal communication between them; the denial of modern education, so no maths, no science, no history and, specially, no analysis of anything, so that there was less chance of a thinking class emerging; the ghettoisation of the majority, and the extreme violence deployed against even minor infractions, such as a boisterous music party.

Trevor was brought up by a single mother, who defied all the norms of her background and time. Abandoned at nine by her family for 12 years, Patricia Nombuyiselo Noah survived on whatever she could scrounge up — mud mixed with water at times — since food was scarce, but she managed to get a basic education from a missionary, which gave her an option to be something other than a maid. Armed with some English and a burning ambition, she did a secretarial course, escaped to the city, hid with prostitutes, had a child with a white man (the worst crime under apartheid), brought the child up in hiding, until such time as apartheid collapsed in the early 1990s. A devout and passionate church-goer, Patricia refused to accept the system and worked around it to get her son a formal education in the ‘white’ school system, read voraciously to him, showed him life beyond black boundaries, opened his mind to a wider world of possibilities, much to her families’ disapproval. “My mom raised me as if there were no limitations on where I could go or what I could do… she raised me like a white kid — not white culturally, but in the sense of believing that the world was my oyster, that I should speak up for myself, that my ideas and thoughts and decisions mattered.” The relationship between mother and son was almost adult-like, with mutual respect and open communication.

Despite getting married later to someone who turned to out to be an abusive man, Patricia somehow managed to convey enough of her dreams to her son, so that he could leave the shanty ‘homelands’ behind. As Trevor says, she was no easy customer. An old school disciplinarian, she didn’t spare the rod, the belt, the shoe. But she instilled in him the capacity to think, to analyse, to argue a point.

Trevor survived. And went on to make a name for himself as a TV and radio host and comedian, first in South Africa, and then globally, eventually landing the much-coveted Jon Stewart slot in hosting ‘The Daily Show,’ on American network Comedy Central, in September 2015. Trevor was then an unknown. No more. His interview style on the show is unique, because he brings a perspective that most white anchors cannot possibly have — and Jon Stewart was astute enough to see that.

One of the major strengths of the book is the prologue to each chapter, which puts the situation discussed in context. Trevor talks of how apartheid took centuries to develop, beginning with the Dutch East India Company landing at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 and establishing a trading colony (a familiar tale). It became a bit more sinister as the original Dutch settlers moved inland, developing their own culture, language and customs. Eventually, they came to be known as Afrikaners — the white tribe of Africa. Everyone had to be categorised, slotted into a race. So, for example, a Japanese was ‘white,’ while a Chinese would be slotted as ‘black.’ But who could tell the difference? It was arbitrary, it was cruel, it was illogical. It stayed that way for nearly three centuries till apartheid ended with Nelson Mandela. And then, as Trevor says, the bloodbath began as tribes, each one with their own axe to grind, turned on each other. “The genius of apartheid was convincing people who were the overwhelming majority, to turn on each other.” They were so busy being angry at one another, they forgot their common oppressor — the white man — even though they outnumbered them five to one.

Trevor is brutally frank about his own actions — his extreme and destructive naughtiness as a child, his brush with the police, his life of crime while working in the ‘hood’ for two years with his two-mates team; DJing for parties, selling pirated CDs and every other thing that came their way, generally hanging around with crackheads and criminals. What Trevor says is that when you are poor, the ethical gradations don’t count for much, although the hood has its own mechanisms for controlling crime in their community.

What is surprising to learn was the level of deprivation even in the 1990s — no sanitation; limited electricity; lack of water, transportation and basic facilities — in a government-sanctioned township like Soweto, where his mother’s family lived. Treated as a ‘white’ kid in Soweto, because of his light skin, Trevor got special treatment in the family and had to be protected and confined to the house, so that he wasn’t taken away by the police. After all, how could a ‘black’ woman give birth to a light-skinned child? That was a crime. Trevor mentions that “my mother’s greatest fear was that I would end up paying the black tax, that I would get trapped by the cycle of poverty and violence that came before me. She had always promised me that I would be the one to break that cycle. I would be the one to move forward and not back.”

The book veers back and forth in time, so that sometimes it’s hard to keep up. Perhaps that is also its saving grace. Otherwise, it might have become too hard-edged. Working in the hood, after finishing his schooling, Trevor learned to hustle and made good money but it was just enough for survival, leaving him with nothing, and he realised its dangerous gravitational pull. Trevor’s decision to pull away after two years to follow a different path, must have taken its toll, but he glosses over those details. However, his views on poverty and helping people, is worth paying attention to. He says it’s not enough to teach a man to fish, you need to give him the fishing rod; without the tools, how is a skill to be turned into cash? Trevor says his life path changed when a friend gave him a CD writer, which he subsequently used to set up a lucrative pirating business. And an option to dream of better things.

Unapologetic, unemotional, until he sees his mother in hospital after she’s shot in the head by his stepfather, Trevor’s story is a glimpse not only into a rare childhood, but also a screenshot of the dying days of apartheid and the mayhem immediately after. The book is beautifully summed up in one of the best blurbs I have ever read, on the backcover: “His experiences are by turns hilarious, dramatic and deeply affecting. Whether subsisting on caterpillars in hard times, being thrown from a moving car during an attempted kidnapping, or simply trying to survive the pitfalls of teenage dating, Trevor’s stories weave together to form an unforgettable portrait of a boy making his way through a damaged world in a dangerous time, armed only with a keen sense of humour — and his mother’s unconventional, unconditional love.”