Lebanon: A Quest for Peace

By Menaal Munshey | Travel | Published 7 years ago

Zaituna Bay

Lebanon is a masterclass in the travails of conflict, and the power of humanity. Beirut, its capital, is a city that never dies. The name literally translates to ‘well of water,’ and it is here that you find wells of altruism and a relentless quest for inclusiveness, peace, and stability. Over its 5,000-year-old history, the Lebanese believe it has been destroyed and rebuilt seven times.

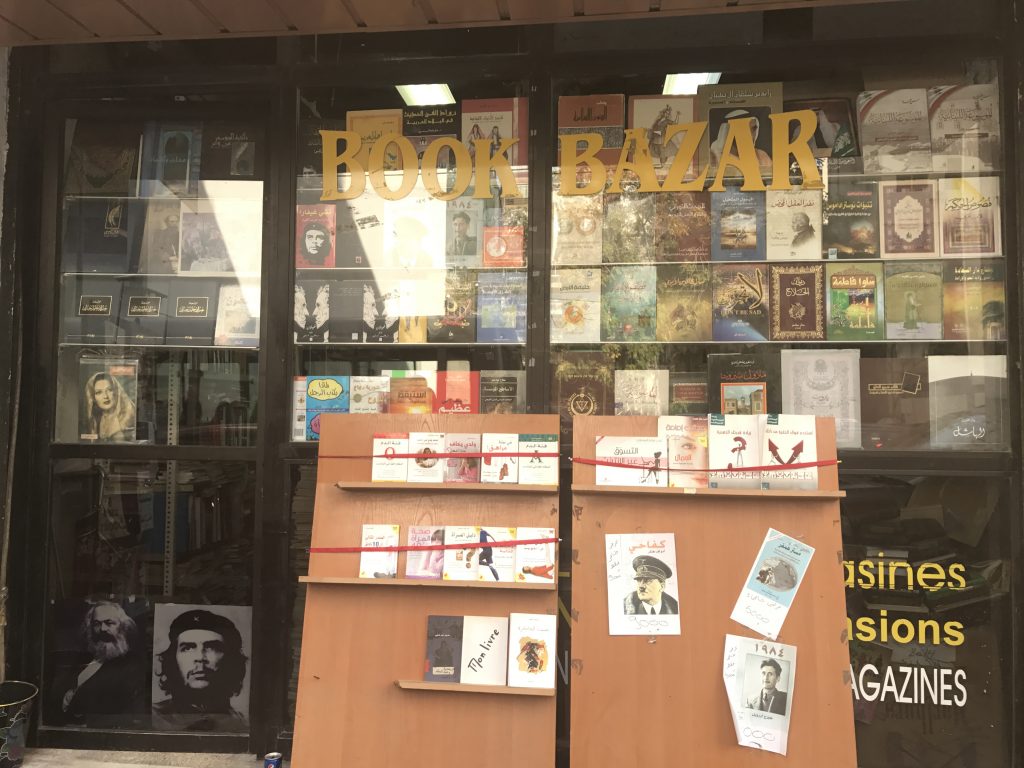

Beirut’s mystique comes from its diversity of cultures and experiences. On the surface, it is a blur of yachts on the marina at Zaituna Bay, swanky souks in downtown Beirut, art galleries in Saifi Village and Gemmayzeh, sunsets on the Corniche, and cocktails in Marr Mikhel. But to delve deeper into Beirut’s soul, you have only to look at its walls. Pastel-coloured restored buildings stand next to bombed-out structures. The walls in Beirut are littered with bullet holes and street art. They are expressions of conflict and violence. Graffiti depicts everything from flowers and bicycles, to guns and slogans of retrieving Beirut. They speak of hope: ‘Live, love Beirut; keep your flame alive; all we need is love, peace and music.’ Lebanese fiction echoes the same stories of pain, suffering and the Lebanese spirit. In Hamra, I discovered Dar Books, my favourite bookshop and café yet, and was introduced to Rawi Hage and Rabih Alameddine’s work. It reminded me of Hemingway’s words: “You are so brave and quiet, I forget you are suffering.”

Boy on a hoverboard on the Corniche.

Sitting in a café near the American University of Beirut (AUB), a pillar of academic and research excellence in the Arab world, it is remarkable how casually strangers converse in a city that has been so deeply divided. We laugh about Beirut’s quirks — the protected status of AUB’s fat cats, the fusion shawarmas, the distinctly un-souk-like souks, the ‘frabic’ (french/arabic) that is seamlessly and poetically spoken, the clubbing in bunkers, and the chaotic, spirited, and ironically named Bliss Street. The city has not lost its sense of humour. Beirut’s energy is infectious. Among the mountains and beaches, churches and mosques, the Mediterranean culture of cafes, healthy living, and happiness is alive and well.

Beirut is a city of approximately two million, and you soon realise the interconnected circles its residents inhabit. In a city of this size, no one has escaped its troubled past. They have lived through a 15-year-long civil war, conflict with Israel (including the 2006 war), and a surprise attack by the Hezbollah in 2008. They have lived through this in a way that is deeply personal. Friends recount memories of living through a civil war, when Beirut was demarcated along sectarian lines into East and West, Muslim and Christian. Many of them lived on the Christian side of the city in Achrafieh as children, and later returned to the Muslim side in Hamra, which was their family’s original home. The Lebanese people have learnt that violence is not a solution. As Albert Camus put it, “But you and I know that this war will have no real victors, and that once it is over, we shall still have to go on living together forever on the same soil.” They want to leave religious divisiveness behind and rebuild cohesiveness and tolerance as a community.

In Lebanon, the conflict and its actors are local. I heard stories of a local doctor being held at gunpoint by a masked  gunman, who it was later revealed, was not only the neighbourhood shopkeeper, but also his medical patient. These coincidences are demonstrative of the personalisation of conflict in Lebanon. At times during the civil war, stores had run out of food and families bought whatever little they could find. Nadia told me how they ate canned tuna for days — and haven’t eaten it ever since. It was a time of fear, but in retrospect, it was also a time for family and friendship. Families spent quality time together, and neighbours formed lasting friendships. It is these coping mechanisms that form the Lebanese consciousness.

gunman, who it was later revealed, was not only the neighbourhood shopkeeper, but also his medical patient. These coincidences are demonstrative of the personalisation of conflict in Lebanon. At times during the civil war, stores had run out of food and families bought whatever little they could find. Nadia told me how they ate canned tuna for days — and haven’t eaten it ever since. It was a time of fear, but in retrospect, it was also a time for family and friendship. Families spent quality time together, and neighbours formed lasting friendships. It is these coping mechanisms that form the Lebanese consciousness.

Over a leisurely three-hour dinner at the legendary Abd el Wahab’s restaurant, friends recount stories of the days when Hezbollah “invaded” Beirut in a battle for power in 2008. Hezbollah draped their flags all over the city, took down Lebanese flags, and placed their fighters across the city. For 48 hours, the city was bombed, shelled, and attacked. Hanaa was stuck in AUB’s hostel at the time. AUB is considered American territory and was not attacked. However, Hamra, where AUB is located, was the central battleground. Hanaa spent those hours covering her ears to block the sound of relentless gunfire and repeatedly called her family, who were at the other end of Beirut. There was no clear enemy, the violence was unpredictable and anything could have happened. She was finally rescued by a friend’s family during a two-hour ceasefire, and reunited with her family outside of Beirut, away from the violence.

Having lived these experiences, how do they feel about Hezbollah? “With Hezbollah, I feel safe” is the response. They were victorious against the ‘invincible’ Israeli army in 2006, and reclaimed large parts of Southern Lebanon. The international press is murky on this, but the Lebanese narrative is relatively clear: Hezbollah saved Lebanon. Certainly, the Hezbollah Museum of Resistance in Mleeta, less than an hour from the Israeli border, depicts brave resistance fighters who hid in underground tunnels for years, joined forces with local citizens, and were successful in defeating the enemy.

The international press often downplays Hezbollah’s role in the 2006 war, and labels Hezbollah as a terrorist group. Friends in Beirut offer differing perspectives: some do believe that Hezbollah often causes many of the problems it purports to solve. It may well be a militant group, but it’s also seen to be legitimate. In the South, Hezbollah is revered. Many believe that IS is afraid to attack Lebanon because of Hezbollah, who are presently (controversially) fighting against them in Syria, in alliance with the Assad regime. Jamal’s brother is a Hezbollah fighter in Syria: without Hezbollah, Lebanon would disintegrate, he says.

Club Bey, Gemmayzeh.

Saifi Art Village

Bookshop in Hamra

In a deeply troubled region, Lebanon is an island of stability and a model of coexistence. Politically, Michel Aoun has been elected as president after two years of an impasse. Under Lebanon’s Constitution, the president must be a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of parliament a Shia Muslim. This tripartite system extends to many political appointments. Economically, Lebanon survived the international economic crisis relatively unscathed and has a thriving banking sector, which can be attributed to the vision of Riad Salameh, governor of the Central Bank, who has spearheaded policies encouraging investment in technology. However, the tourism sector has taken a hit due to the Syrian war. Aanjar, an ancient Umayyad city, is beautiful but tragically empty. The world perceives Lebanon to be unsafe. Counterintuitively Beirut, in parts, feels safer than London. It is closer to the border, so you can see clear indications of the conflict next door.

Driving to the ancient city of Baalbek, the effects of the refugee crisis are visible. I see many Syrian refugee camps on the way, sponsored by UNHCR’s relentless efforts. I learn more about Lebanon’s migration policy at the Issam Fares Institute at AUB, housed in the only Zaha Hadid creation in Lebanon (the internationally reknowned architect, Hadid, was also an AUB alumnus). Lebanon has opened its borders to 1.1 million refugees during the Syrian civil war. To every four Lebanese citizens, there is one Syrian refugee. This is in addition to housing 450,000 Palestinian refugees, 50 percent of whom live in refugee camps.

The Hezbollah Museum of Resistance in Mleeta.

Beirut is a city shaped by refugees. Many Palestinians live in Sabra and Shatila, whereas Bourj Hammoud is home to many Armenians who fled genocide in 1915. In a country of only fout million, refugees make up a huge proportion of the population. In contrast, Europe’s response is shameful. There is a lack of international recognition of how much Lebanon has done, and continues to do.

The UN and the international community must provide Lebanon with increased financial, logistical, and vocal support for their efforts. In addition, concerted efforts need to be taken to provide refugees with equal rights in Lebanon. There has been a considerable increase in child beggars on the streets of Beirut, indicative of the number of child refugees from Syria. Learning from the Palestinian experience, it is hoped that these children will not end up as a “lost generation”. Rather, benefitting from Lebanese education and healthcare, they will be able to build stable and productive lives. The responsibility for this must be shared. After all, as many people tell me, it could have been us.

The 9000-year-old Baalbek.

Exploring Lebanon, you see the aftermath of the Middle East conflict and remnants of its glorious past. It is a country of contrasts. The Bekaa Valley, bordering Syria, is a Shia majority area which now houses Syrian refugees, the majority of whom are Sunni. The Bekaa Valley is also home to 15 wineries including Ksara, which has been producing wine since 1857. We drive through mountain resorts where the Iraqi elite once vacationed. In Baalbek, which has been inhabited for 9000 years by the Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans and Ottoman empires, excavation and restoration has just begun again after the civil war. On the highway from Damascus to Beirut, both being only two hours apart, there is an influx of Syrian cars. The highway was built to connect the flourishing Middle East, which has now been torn apart by imperialist, self-serving, toxic policies.

Beirut taught me lessons on freedom, reconciliation, letting go, moving on, learning, and loving the ‘other.’ The Lebanese spirit and zest for life continues to fight and thrive, even through difficult times. It is a display of resistance, and a recognition that despite the tribulations, life is valuable and precious. As Lebanese-American Kahlil Gibran wrote: “out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls; the most massive characters are seared with scars.” Blooming roses in the Bekaa valley are a pertinent reminder that the Middle East remains resilient in the face of contemporary conflict, and will rise again.