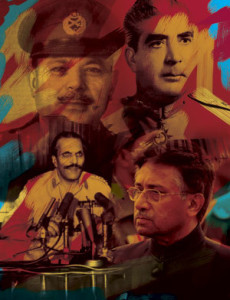

Down, But Not Out…

By Ayesha Siddiqa | News & Politics | Published 13 years ago

First the American operation that killed Osama bin Laden, then the PNS Mehran attack, followed by the mysterious death of journalist Saleem Shahzad — many feel these are changed times for the Pakistan military. The institution was never exposed to the kind of criticism it has had to face in recent months. But does this mean that we have reached that point in time where we need to reinvent the military?

First the American operation that killed Osama bin Laden, then the PNS Mehran attack, followed by the mysterious death of journalist Saleem Shahzad — many feel these are changed times for the Pakistan military. The institution was never exposed to the kind of criticism it has had to face in recent months. But does this mean that we have reached that point in time where we need to reinvent the military?

The answer is no, for the simple reason that the military does not intend to change. Despite all the criticism directed at it, all we heard the ISPR say was that the allegations were basically a conspiracy to defame the armed forces. In any case, the military does tend to reinvent itself frequently by shaping the national discourse in a manner that justifies its power and continued prominence in politics. Just recently, the army tried to do it — yet again — by sending out mass SMSes reminding people of how it had served the nation with its blood and that (in the case of the OBL operation) it had been stabbed in the back. The publicity given to the military’s role in flood relief and other natural disasters is also a way of saving face.

However, if by reinvention we mean an effort to depoliticise the military and make it more professional — even accountable — then the answer is in the negative. The question remains: Why should the armed forces be willing to change their behaviour when all the political stakeholders are unwilling to challenge it? It’s not that the political forces do not want to rein in the military’s power but they are unwilling to take the organisation head-on by putting a stop to all civilian-military partnerships. Today, each political party has some form of linkage or alliance with the army or, is dependent on it.

The political system is structured in a manner that has given state bureaucracies greater power than the political forces. Since 1958 — which is when the military first came into power — it has struck partnerships with civilian stakeholders. GHQ Rawalpindi has always had a political party as its mouthpiece to defend its interests. During the 1970s, it was Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s PPP that was given preference over Sheikh Mujeeb-ur-Rehman’s Awami League whereas in the 1980s, it was the Nawaz Sharif-led IJI, the MQM and JUI-F. These days, the army is once again on the lookout for a key player to safeguard its interests in the Punjab, especially since Nawaz Sharif seems to have drifted away from the GHQ. Many analysts believe that Imran Khan will now play this role.

Theoretically speaking, the military cannot be depoliticised until and unless there is a genuine intent from within (as was the case in China), or pressure from inside and outside, like in the case of numerous Latin and South American military forces), or there is some crisis that makes a reconfiguration of power politics inevitable. In Pakistan’s case, none of the above possibilities seem likely. Unlike China, where the Communist party has greater power to depoliticise the military, there is no neutral or political force powerful enough to do so in Pakistan. We cannot even follow Turkey’s example, where the debate on its inclusion as an EU member state seems to have influenced the domestic political process and resulted in a gradual and relative disempowerment of the military. Finally, given the nuclear deterrence factor, it does not appear possible that there will ever be a decisive war in the region that may result in a political reconfiguration.

Recent events might have made the military unpopular, but have done nothing to defang it.

The writer is an independent social scientist and author of Military Inc. She tweets @iamthedrifter