Colourful Story

By Ghazi Salahuddin | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 21 years ago

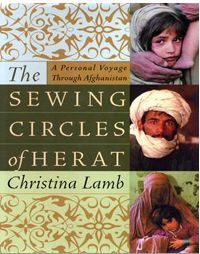

Christina Lamb’s ‘personal voyage through Afghanistan’ paints a vivid landscape of the country, during and immediately after the Taliban. It is so engaging and colourful that the grim realities of the tragic land are transformed into a chronicle of adventure and discovery. We have here a young British woman exploring the rugged land of fearless warriors. She had, after all, been named the ‘Young Journalist of the Year’ in 1988 for her dispatches from Afghanistan. But The Sewing Circles of Herat is more literary than journalistic in its delineation.

Christina Lamb’s ‘personal voyage through Afghanistan’ paints a vivid landscape of the country, during and immediately after the Taliban. It is so engaging and colourful that the grim realities of the tragic land are transformed into a chronicle of adventure and discovery. We have here a young British woman exploring the rugged land of fearless warriors. She had, after all, been named the ‘Young Journalist of the Year’ in 1988 for her dispatches from Afghanistan. But The Sewing Circles of Herat is more literary than journalistic in its delineation.

At the outset, Christina says: “My story like that of Afghanistan has no beginning and no end.” Yet the story has been craftily designed. Its chapters have been interspersed with short snatches from the letters and diary of a somewhat mysterious Afghan woman, Marri, and it is in the last chapter that Christina catches up with her in Kabul. Meanwhile, there are interesting encounters with such familiar characters as Hamid Karzai (whom she had always known as clean-shaven but who was now, after 9-11, growing a beard) and Hamid Gul, whose ISI agents had apparently ransacked her Islamabad residence in 1989 when her visa as a journalist was cancelled. She was allowed back to Pakistan after the government was changed and Hamid Gul was prematurely retired.

All this is artistically embellished with the novelist’s device of meandering through time and place. And the scene is generally set with a poetic touch. Consider these opening lines: “It was a sticky July night, the eve of Princess Homaira Wali’s wedding and she was wandering restlessly in the moonlit garden of her father’s palace in Kabul when she heard the rumbling of tanks. The pale twenty-year old with dark glossy hair and the spirited ranginess of the wild horses she loved to tame, was King Zahir Shah’s eldest grandchild, and her wedding was to be the society event of the summer. The scent of roses hung heavy on the night air and the princess had been thinking about how her life was about to change for as a married women she would no longer be able to sneak off from her bodyguards to go alone to the movies or drive her car around town playing the Beatles.”

True, this is not an imaginary situation. But this comes from Christina’s interview with Homaira in Rome, when a woman of 48 reminisced about the events of July 1973.

That she had had such exciting forays into Pakistani and Afghan societies, quizzing the likes of Maulana Sami-ul-Haq, illustrates how we cosy up to foreign journalists. When they are attractive and smart women, the outcome, in our feudal setting, can be very illuminating. We had some evidence of this in Christina’s earlier book about Pakistan: Waiting for Allah. As an aside, it should be noted that there is now a chain of women reporters covering wars and civil strife for the western media. This is perhaps because women are not considered combatants.

In any case, Christina was obviously able to excite our politicians into candid conversations. To know more about Pashtunwali, she went to see Iftikhar Gilani, “a silver-haired lawyer and politician whom I had first known as a close friend of Benazir Bhutto.” This is how she concludes her account of that meeting: ” ‘We’re talking about a society where in my village a boy and girl kissing is an unpardonable crime seen as worse than murder’, said Iftikhar. ‘The inevitable result is sodomy. It’s the done thing in Pashtun society because of women being shut away in houses. A good-looking boy would have dozens of attempts made on him. I was a very handsome youth and had lots of problems but fortunately our family name and standing protected me. These Talibs have no such protection and it starts with the kind of people who run these seminaries. We used to say, ‘Oh my God, he’s a Talib and that meant he’s sissy or he’s available…’”.

Events and experiences that are narrated in the book relate to her five-month visit to Pakistan and Afghanistan and she returned to Afghanistan after 12 years. She was named Foreign Correspondent of the Year for her reporting from Pakistan and Afghanistan in The Sunday Times following the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001. No doubt, the thoughts that constitute this book are of a more subjective nature than reports written for a newspaper are likely to be. Still, numerous illustrations in the book preserve its historical point of reference.

In many ways, the highlight of Christina’s personal journey is reflected in the book’s title. It is incredibly touching to learn that sewing classes in Herat were a camouflage for literary classes for women. These classes also symbolised the resistance of the cultured city. A child would watch outside in the lane to guard against a Taliban raid. Here is stuff out of which a great movie can be made — Afghan women clandestinely studying Shakespeare, Nabokov and Persian poetry and risking lives to watch a smuggled video of ‘The Titanic.’

It is a measure of the interest that Christina’s version has generated that the book is being serialised in the Sunday magazine of Jang. Afghanistan has traditionally inspired academic and literary exploration. This enigmatic country became an international issue in the early ’80s, when the mujahideen, with ‘covert’ support from the CIA and ISI, took on the Soviet invaders. Since then, Afghanistan has continued to grab international headlines.

Pakistan has retained its umbilical connection to the tribulations of Afghanistan and it is necessary for our intelligentsia to be able to decipher this relationship. Christina provides some very readable insights into a traumatised Afghan society. Hopefully, she can invite the reader to delve into more serious and scholarly interpretations of Afghanistan’s history and its recent tribulations.

Incidentally, the Oxford University Press has just released three significant books on Afghanistan. Two are written by Barnett R. Rubin, an American professor of political science. The Fragmentation of Afghanistan looks at state formation and collapse in the international system. The other book, The Search for Peace in Afghanistan is a study of Afghanistan’s 14-year long civil war and the role that international politics played in this debacle. The third book, by Edgar O’Ballance, a British military officer who became a journalist, is titled: Afghan Wars. It examines “battles in a hostile land, 1839 to the present.”

Will these books help us understand why Pakistan is now about the most hated country in Afghanistan, after we have wounded ourselves so critically in trying to ‘save’ our neighbours?

Ghazi Salahuddin is a respected senior journalist in Pakistan. He currently works with the daily The News and the Geo television network.

No more posts to load