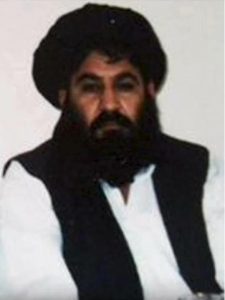

Close Encounters with Mullah Mansour

By Owais Tohid | Newsbeat National | Published 8 years ago

I had no idea that the man I shook hands with and embraced at Mullah Omar’s fortress-like residence in Kandahar was destined to become the Amir of the Taliban. With his stocky build and average height, Mullah Akhtar Mansour was a marginal presence, overshadowed by the more athletic-looking commander, Mullah Baradar, and Mullah Mutamaiyan, information minister in the Taliban government.

Mansour was introduced to me as ‘the guy in charge of Kandahar airport,’ even though he was actually the aviation minister. His claim to fame was that he had downed two Russian helicopters with a rocket launcher. Mullah Omar was so impressed at his mastery of mid-air targets that he gave him the aviation ministry.

It was October 1998, and Mullah Omar was consulting with his coterie before the first round of talks between the Taliban and the U.N. Talking to Lakhdar Brahimi, who led the UN delegation, the Islamic militia was vying for U.N membership. I was covering the event for Agence France Press (AFP).

Eighteen years later, Mullah Omar is dead, Baradar is under arrest, Mutamaiyan is missing, and Mansour has been killed. The slogans however, remain the same. That day, the compound in Kandahar had echoed with cries of ‘Naara-e-Takbeer’ and ‘Afghanistan Islami Emarat Zindabad.’ The same slogans echoed at Mullah Haibatullah’s swearing-in ceremony.

I was in contact with Mullah Mansour again in 1999, when an Indian airliner was hijacked from Kathmandu and taken to Kandahar airport. He was supervising negotiations with the hijackers and the safety of Indian passengers. The negotiations resulted in the release of three militant leaders languishing in Indian prisons: Sheikh Omar, now a condemned prisoner in the Daniel Pearl kidnapping and murder case, Masood Azhar, who heads the banned Jaish-e-Mohammad, and Mushtaq Ahmed Zargar, who kidnapped the daughter of the then Indian Home Minister, Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, in exchange for the release of five of his comrades.

Mansour had participated in the jihad against the Soviet forces since his youth, fighting under the mujahideen commander, Younis Khalis, who led Hizb in the 1980s. He was from southern Afghanistan, like other founding members of the Taliban movement. Hailing from Malwand town near Kandahar, he belonged to the Ishaqzai tribe with Durrani lineage. In the late ’80s, Mullah Mansour moved to Quetta for a while and then to the Jalozai refugee camp in Nowshera, where he studied at a seminary.

Mullah Mansour and Baradar are said to have saved Mullah Omar’s life after 9/11. The story of their fleeing the US bombing of Kandahar astride motorbikes, wearing burqas, is quite well known in Taliban circles. Some jihadis say that the burqas, were later returned to the family of the woman they were taken from, and as a gesture of respect and honour, Mullah Omar married the burqa-owner.

As acting Amir, Mansour kept Mullah Omar’s death a secret. When the news became public, it made the rest of the Taliban distrust him, which embittered him and turned him against talks with the Afghan government. Omar’s brother, Mannan, and son, Yaqub, challenged Mansour’s authority and refused to take an oath of allegiance to him. His rivals also accused him of drug-trafficking and pocketing hefty amounts, adding that he had embezzled funds while handling the finances of the clandestine movement post 9/11. Mansour tried to prove his radical credentials and regain the loyalty of estranged militants by staging fierce attacks in Afghanistan, including the invasion of Kunduz and the defeat of Da’esh in Nangarhar.

For over a decade, he travelled frequently to Dubai and visited Iran on a Pakistani passport, using the fake identity of Wali Mohammad. “He held meetings with Afghan businessmen and Islamic nations in the UAE to discuss the holy Afghan war and raise funds for Taliban operations,” said Taliban spokesman, Zabeehullah Mujahid. He described Mansour’s visit to Iran as due to “ongoing battle obligations,” adding that Iranian border police failed to recognise him as he was travelling under the fake identity of Wali Mohammad.

“He was always fond of journeys. He loved travelling in planes, riding motorbikes, driving cars. It was his hobby,” says a Taliban leader. But his militant journey was cut short by a US drone just after he entered from Iran into Balochistan province. Mansour leaves behind a legacy for Taliban warriors and a trail of uncertainty for the future of the Taliban, possibly embroiled in the biggest war the Islamic militia has ever fought for its existence.