Book Review: Women Writing Violence

By Subuk Hasnain | Books | Published 10 years ago

A community is, at a basic level, a group of people who share a particular characteristic in common. A nation itself is also a form of community, and multiple communities are found within one nation. There are neighbourhood communities, religious communities and racial communities. But they are all concrete, visible and very much alive. What Shreerekha Subramanian unpacks in Women Writing Violence is abstract, beyond the world of the living and the dead. She seeks alternate or imagined communities of those who suffered and died during the violent process of nation-building. In other words, she takes the concept of community and applies it to the deceased, to see what shared experiences and situations would bring them together.

In order to search for these imagined communities, there was no better place for Subramanian than the literary novel. It gave her room to make multiple interpretations and look for communities without any limitations. She selects Toni Morrison’s Paradise, Edwidge Danticat’s The Farming of Bones, Bapsi Sidhwa’s Cracking India, Tehmina Durrani’s Kufr, Amrita Pritam’s Pinjar and a few other novels to visualise the kind of imagined communities that are given birth to through unheard voices of women and those on the sidelines of the more prominent narratives of creating a nation.

Bapsi Sidhwa’s Cracking India, for instance, is set during the creation of India and Pakistan. In it, Subramanian explores an imagined community that emerges from the tale of a woman’s body. Lenny, a young girl from an affluent family in India, is a crippled seven-year-old and distant from the pain of the partition. Lenny tells the story of Santha, her beautiful Hindu ayah. Santha is raped and destroyed by Sikh, Hindu and Muslim men, who had once placed her on a pedestal. Subramanian moves past the “larger historical events and presences” of 1947 that unfold alongside Santha’s story and focuses on the “alternative community” that emerges within Sidhwa’s novel. In her conclusion for this chapter, she writes: “Imagined community exists in all that is not narrated, the moans of the rape victims, the anguished guttural pleas of women who ask to be killed to spare more torture… Lenny’s scream and Santha’s ‘wide-open terrified eyes’ are the beginning and end of the sentence, which spells out the imagined community of Lahore’s partition. It hints at bodies of pain, the tale itself remains to be told.”

The community she discovers in Sidhwa’s novel is “an alternative community of women in motion, women who were severed from their homes and pasts and thrown into the historical turmoil of nation-making.” Subramanian goes on to write that Santha’s absence from the text “signifies a communion between Santha and all the dead, disappeared and dispossessed of this period in time called the Partition.”

In Morrison’s Paradise, Subramanian finds a slightly different alternate community. Paradise is a story about a “band of African Americans trekking across the United States in the late nineteenth century to form an ideal community of autonomous farmers in Oklahoma.” Constantly dealing with rejection, the leader of the community decides to settle in a town called Haven that is later renamed Ruby. Outside Ruby, there is a convent occupied by women who “listen to a leader of their own choosing,” and disobey the laws of the patriarchs of Ruby. The men “act to eliminate what seemingly threatens their idyll” and “the novel opens on this moment when the men are shooting the women in the convent.” These same women who are shot at the beginning of the novel are “present, travelling, talking and addressing people in different cities in the closing sections,” thereby giving death a new, more powerful meaning. Later in the chapter, Subramanian explains that despite being killed, the women collectively return in imagined spaces in the novel, “in more powerful forms to do more powerful labour.” She writes, “the massacre does not stop [the women] from the act of imagination. They continue imagining community with the dead so that after being shot, violated and bloodied, they travel across the nation in a greater state of liberation.”

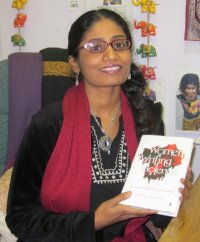

A Humanities professor at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, Subramanian’s previous publications address some of the novels she discusses in Women Writing Violence. Throughout her educational career, Subramanian has focused on English literature and creative writing. She also earned a PhD in comparative literature from Rutgers University and was the first recipient of the Marilyn Mieszkuc Professorship in Women’s Studies in 2008. Her research interests, that are apparent in Women Writing Violence, include third world feminism, women writers and the 18th — 20th century novel. And she has always been intrigued by loss, voices of the absent, the disempowered and the disenfranchised.

A Humanities professor at the University of Houston-Clear Lake, Subramanian’s previous publications address some of the novels she discusses in Women Writing Violence. Throughout her educational career, Subramanian has focused on English literature and creative writing. She also earned a PhD in comparative literature from Rutgers University and was the first recipient of the Marilyn Mieszkuc Professorship in Women’s Studies in 2008. Her research interests, that are apparent in Women Writing Violence, include third world feminism, women writers and the 18th — 20th century novel. And she has always been intrigued by loss, voices of the absent, the disempowered and the disenfranchised.

The intricacies that Subramanian explores make this book a difficult, dense read. One has to deconstruct their own concept of community, and really be open to Subramanian’s ideas, because they are very abstract. She writes, “since my definition of community demands a variability, the imagined community with the dead shifts in appearance, meaning and locus in each of these novels.” Even though she provides readers with a background of the characters she explores, the setting and contexts she uses are not always easy to understand, unless one has read the novels she addresses in great detail. The academic language is also difficult to get through and the reader might have to go back and forth between the pages to make important connections. Subramanian’s book is a highly detailed text that explores a complex intersection between women, violence and imagined communities that emerge from stories of loss — and that, in itself, is a lot to comprehend.

This review was originally published in Newsline’s June 2014 issue under the headline, “Exploring The Imaginary: Women, Violence And Community.”

No more posts to load