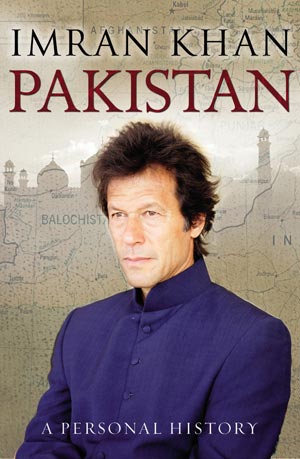

Book Review: Pakistan — A Personal History

By Amir Zia | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 12 years ago

Imran Khan’s latest book, Pakistan — A Personal History, may appear as confusing as his politics. The former cricketer-turned-politician’s shallow and clichéd interpretation of Pakistan’s history, repeated assertions of its Islamic identity and his dabbling in the world of spiritualism, in which he finds gurus who predict the future and reveal the past, are indicative of a mind which is orthodox.

Imran Khan’s latest book, Pakistan — A Personal History, may appear as confusing as his politics. The former cricketer-turned-politician’s shallow and clichéd interpretation of Pakistan’s history, repeated assertions of its Islamic identity and his dabbling in the world of spiritualism, in which he finds gurus who predict the future and reveal the past, are indicative of a mind which is orthodox.

This book may please the right-wingers, but it will disappoint all progressive Pakistanis as well as western readers as Khan is projecting himself as a messiah of this violence-ridden nation which is struggling to cope with the demands of the 21st century.

Khan has gone the extra mile to conjoin democracy with Islam and Islam with democracy, although the two stand in stark contrast to each other. Islam allows no dissent, alteration and divergence from its fundamental teachings. Democracy is all about dissent and the will of the people. It draws its strength from secularism, which does not allow interference of religion in the affairs of the state. There can be a secular state, which is undemocratic, but no democratic state can exist without secularism as its cornerstone. This, perhaps, is one of the key reasons behind Pakistan’s flawed democracy, along with the strong tribal and feudal systems that remain a dominant force in Pakistan’s politics, leaving little room for democracy to take root, flourish and deliver.

Yes, even a political science graduate can tell you that democracy is a product of the industrial revolution and a strong, educated middle-class which, unfortunately, is found wanting in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and most Muslim countries.

Khan’s personal analysis of the origin and spirit of the Pakistan Movement underlines his simplistic and superficial understanding of those times. In fact, it appears more akin to former military ruler General Zia-ul Haq’s distorted and twisted propagandist history, which still remains spart of our curriculum. For instance, Khan, in his zeal to promote the Islamic basis of Pakistan, equates Quaid-e-Azam Mohammed Ali Jinnah’s religious views with those of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi by saying that both stood on the same page vis-a-vis the role of religion in politics.

All those who have studied the Movement are aware that Jinnah opposed Gandhi’s explicit use of Hindu symbolism in politics, and argued that it would eventually divide the country. This had been Jinnah’s position even in the 1920s, when many Indian Muslims were passionately supporting the Khilafat Movement to save the Ottoman Empire after the end of World War I. The movement was backed by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress in an attempt to lend steam to their non-cooperation movement against the British Raj. But Jinnah was among those frontline leaders who openly opposed it on grounds that it was fundamentalist in nature and essentially a flawed cause. Jinnah’s position and foresight proved right when religion became the dividing line in British India, and the one-time champion of Hindu-Muslim unity had to lead the Pakistan movement to ensure the political and economic rights of Muslims living in the Muslim-majority parts of India. A treasure trove of documents, research and literature are available on these historic events, but perhaps they do not fit the narrow prism through which Khan wants us to view the Pakistan Movement.

Much in the nature of a born-again Muslim, Khan keeps revisiting themes of cultural hegemony of the West, and glorifying the traditional values and conventions at home. The confusion in his mind is glaring when in one breath he admonishes the West and its ways and, in the other, praises it for establishing “a proper welfare state.” He repeats the clichéd and overused quote of an Egyptian scholar Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905), in which he says that he “saw no Muslims in Europe but a lot of Islam.”

The book remains repetitive in terms of certain themes, including the writer’s own spiritual experiences, glorification of tribal values and customs, Islam’s democratic principles which he fails to define, and the corruption of the country’s ruling elite.

Those parts of the book that deal with Imran Khan’s struggle and achievements as a professional cricketer are inspiring — especially the manner in which he fought injuries at the peak of his career and led the team to the World Cup victory in 1992.

“The moment you relax and stop pushing yourself is the moment you start going downhill,” Khan writes. “I first strove to play cricket for Pakistan, then my goal became to be my country’s best all-rounder, then the best fast bowler. From there I wanted to become the best all-rounder and the best fast bowler in the world. When I was made captain the ambition became turning the team into the best in the world….” (Page 120-121).

For Imran Khan, life is a journey of achieving one goal after another. From cricket to building the first cancer hospital, and then a university, then aiming to build two more hospitals — indeed, it is the story of a high achiever in life. Khan’s romance with politics, his years in the political wilderness and his passion to emerge as an alternate to the corrupt ruling elite, all are nicely summed up in the book.

His brief anecdotes with frontline politicians — Nawaz Sharif, Benazir Bhutto and General Zia-ul-Haq — offer an interesting read. For instance, details of a 1987 episode in which Nawaz Sharif, then chief minister Punjab, imposing himself as captain of the Pakistan side for a warm-up match against the visiting West Indian team at Lahore’s Gaddafi Stadium and actually coming out to open the innings offers an insight into General Zia’s protégé.

“None of the team could believe what we were seeing; he (Nawaz) was going to open the innings with Mudassar Nazar against the West Indies, one of the greatest fast-bowling attacks in cricket history. Nazar wore batting pads, a thigh pad, chest pad, an arm guard, a helmet and reinforced batting gloves, while Sharif simply had his batting pads, a floppy hat — and a smile… I quickly inquired if there was an ambulance ready” (Page 131-132).

The portion where he talks about building a cancer hospital in his mother’s memory is moving and underlines Khan’s tenacious nature. Although Khan has devoted a chapter to his failed marriage, many readers might wish for more details about the circumstances that led to his break-up with Jemima. But Khan remains a fiercely private person.

The tribal system, its code of honour and values are a constant refrain in the book. Khan maintains that the tribal areas were “crime free” before the upheavals of the recent years, ignoring the fact that before the start of the war on terror, the entire belt remained the epicentre of smuggling and gun-running in the region. The known criminals and absconders used to take refuge in these areas and vehicles snatched from various parts of the country landed in the tribal belt. But Khan, in his zeal to glorify tribalism and the jirga system, shuts his eyes to all these facts. He makes a passing reference to the tribal practice of ‘honour’ killings which are being endorsed by jirgas in the rural areas. In fact, he views these jirgas as an “ancient democratic system.” The oppression, the backwardness, the myopic worldview and total alienation from the modern world, all of which stem from tribalism, fail to bother the Khan.

The writer’s interpretation of the war on terror also reveals his limited understanding of local, regional and global politics. Khan argues that extremism and terrorism are the result of US presence in the region and he believes that once the US walks out of this region, terrorism will end.

Unfortunately, he fails to point out how that will happen when terrorists and terrorism have penetrated deep inside the social fabric of Pakistan. The author ignores the fact that extremism and terrorism remain a potent threat to the state of Pakistan today. This twin evil can only be fought when political forces and the establishment confront these extremist forces and defeat them both ideologically and practically.

Overall, Imran Khan’s knowledge and understanding of the history of Pakistan is deeply flawed. Consequently, one would refrain from placing Imran Khan’s Pakistan — A Personal History in the league of the greats like Jawaharlal Nehru’s The Discovery of India, or Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s The Myth of Independence, which are considered classic political literature in South Asia due to their vision, deep political and historical insight and intellectual content. It is nowhere near even Benazir Bhutto’s Daughter of the East, or Pervez Musharraf’s In the Line of Fire, which offer fresh insights, perspectives and details on issues that are critical for Pakistan.

This book review was originally published in the December 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Confused ‘Messiah.'”

Amir Zia is a senior Pakistani journalist, currently working as the Chief Editor of HUM News. He has worked for leading media organisations, including Reuters, AP, Gulf News, The News, Samaa TV and Newsline.