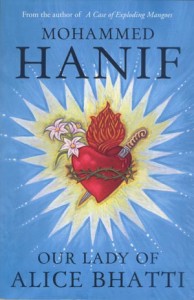

Book Review: Our Lady of Alice Bhatti

By Amna R. Ali | Arts & Culture | Books | Published 13 years ago

Hail Alice Bhatti!

In a literary cosmos populated by choohras and charyas, Mohammed Hanif’s second novel lifts the lid on a ubiquitous underbelly, in a world out of joint, where Christian preachers are called dogs and beggars try new tricks every day. Just like Hurricane Katrina regurgitated the dark dregs of an inordinately duplicitous social order, Our Lady of Alice Bhatti sweeps aside blurry perceptions, and underlines prejudices to take a dig at Pakistan’s tragically splintered society. “These Muslas will make you clean their shit and then complain that you stink,” says Joseph Bhatti, Alice’s father, tweaking subliminal images of the deprived choohra lifestyle.

There are varied aspects to Hanif’s new novel, but it is primarily a provocative tale of love and longing set in an urban Karachi landscape, at the Sacred Heart Hospital for All Ailments. Nurse Alice Bhatti is an attractive, lithe young Catholic nurse, recently released on bail from the Borstal Jail for Women and Children where she was sent for bashing a famous surgeon with a flowerpot and nearly killing him. The bail is arranged by her father Joseph, a self-styled seer and healer who gratifies a lawyer with his remedy for ulcers.

She interviews with the Sacred Heart for the post of a junior nurse and consequently juggles shifts at the orthopaedic ward and the Manto-esque Charya Ward, the Centre for Mental and Psychological Diseases, strictly cautioned by Senior Sister Hina Alvi: “Just remember it’s a nuthouse and there’s a reason for that.” Nurse Alvi pontificates further providing a truthful parable, “But as far as I am concerned the whole country is a nuthouse.”

Nurse Bhatti’s placement is the prelude to her romance with an ex-bodybuilder and yob, Teddy Butt who, besides being conferred the title of Junior Mr Faisalabad, is also a member of The Gentleman’s Squad, an underground unit of ex-thugs who flog their services to the police. Butt’s character borders on the absurd: he brandishes a gun to declare his love but waxes his entire body; he is sinister while dealing with crooks but insecure in the bedroom. His romance with Alice veers on the obsessive and is dangerously disjointed — sometimes tender, often farcical.

The Sacred is inhabited by various sorts. Seventeen-year-old Noor, a self-taught ward boy who works gratis while caring for his dying mother, has an avid crush on the lissom Alice and whose erudite observations put a finger on the pulse of love and local politics: “This whole business of love is a protection racket, like paying your weekly bhatta to your local hoodlum so that you are not mugged on your own street.” There is the well-mannered Dr Jamus Periera, who is kinder to the have-nots in comparison to the other senior hospital staff, but who “is too polite to point out that not all Christians are sweepers”; the leering and egotistical orthopaedic unit chief simply known as Ortho Sir; the indomitable nurse Hina Alvi, whose frequent commentary often elucidates some historical home-truths; and Joseph Bhatti, Alice’s father, proud sanitary worker par excellence, who has simultaneously perfected the art of unblocking drains and curing ulcers. Their virtues and peccadilloes make them compelling individuals, portrayed by an author who gets them to speak as ordinary characters and a whole section of society at the same time.

Hanif’s novel evokes a Karachi where an underprivileged underclass has no alternative but to continue to earn their daily bread — they are the underbelly that man hospitals, fix telephone and electricity wires, police its environs and circumvent a schizophrenic city in an attempt to survive its oppression and violence. It’s a city where there are random shootings, horrific accidents, ethnic violence, shutter-down strikes, riots, body-parts in gunny sacks and hospitals that receive the injured and the dead. Amidst this hullabaloo, fishermen lay nets and dog-lovers walk their pets — life goes on.

Hanif canvasses a territory where oppression is the norm: “Lewd gestures, whispered suggestions, uninvited hands on her bottom are all part of Alice Bhatti’s daily existence.” Alice constantly protects herself from harassment: “She tries to maintain a nondescript exterior; she learns the sideways glance instead of looking at people directly…She never eats in public” because she believes that “if you show your hunger you’re probably asking for something.” Oppression also comes in serious forms of discrimination: Alice is the main accused in a murder she didn’t commit. The ignominy of her class is her everyday reality, but even though she is often stuck between a rock and a hard place, she has better things on her mind; Alice is a fighter, a passionate lover of ‘Lord Yasoo’ and a miracle-worker.

In catechism, the definition of miracle is usually an unexplainable cure from disease. Alice’s oeuvre is she can guess how people will die; she also “cures the incurable.” How many miracles must she perform to enter the canon of saints? When will Our Lady of Alice Bhatti be invoked? Hanif prepares Alice Bhatti’s case for sainthood; juxtaposing the ridiculous and serious, employing wry humour to illuminate a sombre state of affairs.

Mohammed Hanif skilfully crafts the story to override themes — the issues of caste and creed, violence, injustice and oppression are present — to dwell on them is an individual choice. In this book, it is the exciting story of a woman’s life that is ultimately engaging. The narrative unfolds to reveal the sensitive and brutal territory of Alice Bhatti’s existence where we enjoy and despair the multitudinous universal feelings of love, loss and hate.

Click here for more on Mohammed Hanif.

This book review originally appeared in the October 2011 issue of Newsline under the headline “Hail Alice Bhatti!”

The writer is a former assistant editor at Newsline