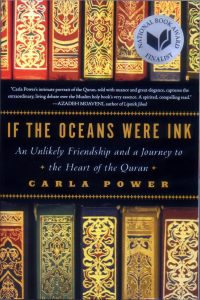

Book Review: If the Oceans Were Ink

By Afsheen Ahmed | Bookmark | Published 7 years ago

If The Oceans Were Ink was a Pulitzer Prize Finalist, a National Book Award Finalist, and hailed by the Washington Post as “mandatory reading for the 52 per cent of Americans who admit to not knowing enough about Muslims.” And the laurels are easy to understand.

Post as “mandatory reading for the 52 per cent of Americans who admit to not knowing enough about Muslims.” And the laurels are easy to understand.

Theirs was an unlikely friendship that led to an even more unlikely — and probably first-ever year-long conversation between a traditional Muslim alim and a secular, liberal American woman journalist. This, in the calm and ordered environs of Oxford University. The conversation focused on Islam, and its core — the Quran — its impact on its followers and on the world; its message and how that has been interpreted by different fiqhs and new-age ‘scholars’; its power to both ignite and to comfort.

Carla Power is an American journalist who has led an itinerant life from childhood (with a father enamoured of Islam yet unable to ‘believe’), living in Muslim societies like Kabul, Cairo, Delhi and Tehran. She now writes for Time, was a foreign correspondent for Newsweek and a contributor to The New York Times magazine and Foreign Policy. A graduate with a degree in Middle Eastern Studies from Oxford, as well as degrees from Yale and Columbia, Power wanted to go where few journalists have ventured to go before: to understand the Quran without becoming a convert, in an attempt to make sense of the devastation wrought in the world post 9-11 in the name of Islam, and the equally short-sighted reactions to this new world order. The book was a journey undertaken to help increase an understanding of and bridge one of the greatest divides shaping our world today. And also to see how Islam impacts, not just the larger community, but also an individual.

In this case, the individual on whom the book is based, is unique. Power’s association with Muhammad Akram Nadwi (referred to as the Sheikh), began in the early 1990s when he was conducting research for a number of years at the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies. Their association continued. And Power’s year-long conversation in 2012-2013 with her long-time colleague and friend, the Sheikh, took place over countless cups of tea and cakes at cafes in Oxford; at the Sheikh’s home with his wife and daughters; and while attending his standing-room only seminars either in Cambridge or elsewhere in the UK. To get a better understanding of his background, Power travelled with the Sheikh to India, to Uttar Pradesh to the village he was born and raised in — Jamdahan, where she met his mother and other family — and to the seminary he studied in to become an alim, the prestigious Nadwat al Ulema in Lucknow. Here he was trained in the traditional Islamic disciplines, which include the Greek philosophers, and went on to do a PhD in Arabic literature from Lucknow University. Thereafter, the Sheikh’s mentor sent him to Oxford to research, to teach, to reach out. And so, Sheikh Akram, a village boy who, through sheer faith and breadth of knowledge and vision, became a highly respected and sought after scholar of Islam.

Published widely in Urdu, Persian, Arabic and English, this traditional alim has never seen a movie, and does not possess a TV. But he is a connoisseur of Urdu poetry and is the first, and perhaps only, Muslim scholar to have completed a 40-volume biographical dictionary of, the hitherto unknown, unacknowledged, women scholars of the Prophet’s hadith, known as al-Muhaddithat.

A notoriously private person, the Sheikh agreed to the conversation with Power because he too wanted a better understanding of the ‘other’ and to see where the lines converge (with a western worldview) and where they diverge. None was sure of the outcome. In the first discussion about the first sura of the Quran — the Al-Fatiha — the last three lines of the sura led to an uncomfortable start to the journey. On Power’s inquiry on who was being referred to when the prayer asked to be saved from the “fate of those who had incurred God’s wrath,” the Sheikh calmly said most people thought it referred to the Jews (Power’s mother was a Jew) and to the Christians because, they too, went to extremes in confusing their prophet, Jesus, with the divine. However, he went on to say that he did not believe the last line referred to those groups specifically, but to “any Muslim who veered off piety’s path.”

This was the start of many such conversations. The first lesson set the tone. Power acknowledges she heard truths she didn’t want to hear and realised the conversation “would test the limits of my tolerance.” And therein lies the pleasure of reading the book. Surprisingly candid, both participants hold on to their worldviews, while trying to find common ground. What made it work is adab, a quaint word, the crux of good manners and humaneness. The Sheikh’s adab, says Power, went beyond graciousness.

Power did not shy away from asking questions on topics as diverse as girls’ education (all six of the Sheikh’s daughters have been educated in normal British schools), hijab, child marriage, jihad, men-women relations, etiquette related to grieving. The Sheikh did not shy away from answering either. In most, he held to traditional rulings. However, in a surprising turnaround, after repeated discussions and arguments put forth by his female students, backed by logic and research, he changed his views on child marriage, asserting that he had revised his position after revisiting traditional sources and had found a sound fatwa by an 8th century judge and jurist, Ibn Shubruma, against the practice of child marriage. The Sheikh went on to say there was a need to write new texts, particularly by women, in the pursuit of justice, taking into account the Quran and the Sunnah, since “women were not present when these legal opinions were being written earlier.”

Frank and matter-of-fact on matters relating to sex, the Sheikh reiterated that since Islam was a part of life and sex a part of it, “Muslims should not be shy to ask questions and whether they were approaching it in a spirit of piety.” He said the Prophet himself used to hold special women-only sessions, so that there would be no excuse for bashfulness. “Shy people,” he said, “and arrogant ones, never learn.”

As to the hugely controversial passage from Al-Nisa (The Women), verse 4:34, wherein, according to translators, it says men are in charge of women and their guardians and they have the right to chastise them, as a last resort, if they don’t obey, it has been used by orthodox jurists to curb women’s rights and movements, contrary to what was prevalent at the time of the Prophet (PBUH). The Sheikh suggested looking at the entirety of the chapter, not just this verse. The revelation about women inheriting was earth-shaking, he said. It did not go down well in the society of that time. Today, there are complaints that women are only entitled to half the share of men. But that, according to Islamic law, is wholly hers, to be used as she likes. And, as Power points out, till 1870, under British Common Law, a married woman, legally speaking, did not exist: she couldn’t inherit (the starting point of Downton Abbey, Pride and Prejudice, Sense and Sensibility) or keep her earnings! In the US, it was only in 1900 that women were given the right to control their own property. There are no spiritual or other differences, said the Sheikh. Men and women “have the same soul, are subject to the same laws.” And about the ruling on men being allowed to beat their wives, the Sheikh was emphatic: “there is no hitting happening in the Muslim world, according to Islamic law. Besides, the Prophet never hit his wives. ‘The best among you,’ said the Prophet, ‘is the one who is best towards his wife.’”

As the Sheikh explained, the Prophet was far more flexible than the legal scholars who followed him and developed fiqh. The way he saw it, “law had hardened into a career,” and the Sheikh was adamant about avoiding the stifling effect of the four major schools of fiqh — ranging from the more liberal Hanafi school, practiced in South Asia, to the more strict Hanbali school, common to Arabia. He felt that these different fiqh had “encouraged divisions and distracted people with niggling differences of opinion.”

In this age of rising Muslim anger against the West, the Sheikh explained, somewhat wearily, that verse 4:76, better known as the ‘Verse of the Sword,’ was revealed at a critical moment in the new Muslim community’s existence at Medina, when they were under attack from the far more powerful Quraysh and their allies. He says it is a tragedy that attention to context is ignored when this verse is used by extremists on both sides to ignite passions, as proof that permission is given for this in the Quran. According to the Sheikh, contemporary jihads are being waged by men, not from an excess of piety, but a lack of it! Also armed jihads “can only be waged by legitimate Islamic leaders operating openly. And jihad must not target fellow Muslims.” Today, the vast majority dying in the name of jihad are Muslims.

So, is there a solution? “It would be better if we didn’t do anything. You can quote me on this,” said the Sheikh. “All this fighting, this jihad, this shariah, it would be better if Muslims just stop and do nothing. Don’t work. Don’t pray. Nothing. If you don’t do anything, then it would be better. Every modern political struggle undertaken under the mantle of Islam has failed. Islamist political programmes are mostly negative, more focused on getting power than governing effectively.” As expected, this view of matters invites a lot of scathing criticism from fellow religionists.

And so to the last lesson of the book — and of life: death. Power, a non-believer in any faith, writes of the last of the eight-hour Magnificent Journey sessions in Cambridge, covering the last sections of the Quran. The message — this world is an illusion, “the next world our destination.” And the Sheikh didn’t mince his words when asked if hellfire was a metaphor; “The fire is fire,” for those who did not submit to God. And so Power asked the question that had been on her mind in the final tea session; “What will happen to me, who believes in some sort of God, but am nowhere ready to submit to a faith?” Although, she concedes she remains an “appreciator of Islam.” The Sheikh was gentle, as always, but firm. “People have no salvation until they believe there is no one to worship except Allah… when I am asked whether I warned people about the Fires of Hell, I want to be able to say that I had. Those who were my friends, like you, I should certainly try to save them.”

The year-long conversation had come to an end. The Sheikh’s encompassing worldview had made the journey possible. With a non-believer. And a woman at that. In the early days of their acquaintance in the 1990s, the Sheikh had comforted Power by reciting, in Urdu, an elegy written by Iqbal for his mother, when her father died in a tragic accident, in Mexico. And, almost eerily, towards the end, when both Power and the Sheikh lost their mothers within a few weeks of each other, Power found it strangely comforting that in Islam, as in Judaism, it was food, not

flowers, that were brought to comfort the bereaved. And, regardless of beliefs, as both agreed, some emotions are universal: even “piety can’t fill the hole a mother leaves when she dies.”