Book Review: Mr and Mrs Jinnah

By Raheel Shakeel | Bookmark | Published 7 years ago

Sheela Reddy

On a breezy Bombay evening in late April, 1918, a young debutante stepped out of the Palladian halls of the Petit Mansion, to make her way to the South Court Residence, on Malabar Hill. This was far from an evening stroll to shoot the breeze. This fugitive of love was “renouncing the old life, with its wealth and luxury and security that her parents provided,” to wed an enigmatic but brilliant lawyer without her parents’ knowledge or blessings. The prospective bride and groom were a galaxy apart in terms of age, temperament, upbringing and religion and yet she would tread on towards his embrace.

On a breezy Bombay evening in late April, 1918, a young debutante stepped out of the Palladian halls of the Petit Mansion, to make her way to the South Court Residence, on Malabar Hill. This was far from an evening stroll to shoot the breeze. This fugitive of love was “renouncing the old life, with its wealth and luxury and security that her parents provided,” to wed an enigmatic but brilliant lawyer without her parents’ knowledge or blessings. The prospective bride and groom were a galaxy apart in terms of age, temperament, upbringing and religion and yet she would tread on towards his embrace.

Ruttie Jinnah and Muhammad Ali Jinnah are the seminal couple of Pakistan, but regrettably all the details of their volatile relationship seem to be veiled in mystery. Ruttie stands as a bigger paradox than even the elusive Jinnah. Despite being the ‘Mother of the Nation,’ by way of her association with Jinnah, she appears as a mere footnote in almost all historical accounts. The book Mr and Mrs Jinnah, by Sheela Reddy is a laudable attempt to shine a light on the romance and subsequent marriage that shook India. By no means is this a drab account of one fact after another, littered with thick academic prose. Instead, the author narrates the story with the tenderness and eloquence the subject matter requires. If one would overlook the historical underpinnings of the narrative, the book could easily be taken as a heart-rending romance.

The glamorous world of the cultural and intellectual elite of pre-Partition India is brought back to life in vivid detail. The regal balls, the grand banquets, evening soireés and the summer exodus of Bombay’s well-heeled to the hills, all kept pace even between the two world wars and the looming spectre of Independence. It’s in this milieu that we find Jinnah, a tall, immaculately dressed, upstart Karachi lawyer with no connections, carving his place in Bombay’s elite. His charisma and brilliance would win him many powerful friends, including the baronet, Sir Dinshaw Petit, Jinnah’s future foe and aggrieved father-in-law.

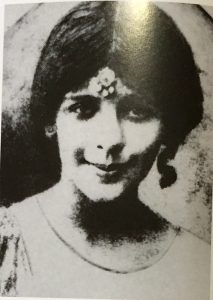

The reader is also introduced to a young, carefree Ruttie, with her dazzling looks, exquisite style and sophistication that made her the most eligible bachelorette in Bombay. In due time, she would be smitten by the suave yet sullen lawyer for whom she would lose her inheritance, be excommunicated from the Parsi faith and be cast out of her community and family.

It is in the later chapters, after their clandestine wedding, that one begins to sense the isolation Ruttie Jinnah would have felt. On the one hand, she was a pariah in the city of her birth and on the other, had to deal with a loyal but emotionally unavailable spouse. Instead of falling into despair, or returning to the comfortable confines of the Petit Mansion, she would plod on as Jinnah’s lieutenant, making public appearances with him not as a trophy wife but as an intellectual equal and giving rousing public speeches when the opportunity presented itself.

Though draped in the finest Parisian fashions, Ruttie was a rebel at heart. Political activism in this exciting time was one of the reasons she chose to be by Jinnah’s side. What else could be expected from a well-read lady who counted among her influences Emile Pankhurst (a firebrand British feminist of her times), Oscar Wilde and the Bronte sisters.

As this dynamic duo started becoming a formidable force in local politics, domestic rifts started to appear. As Jinnah’s political star rose, Ruttie consigned herself to the shadows. From her newfound prominence she would soon recede into political irrelevance. Never again would she attempt to regain that role. In the later chapters, the heat of the Gandhi-Jinnah rivalry takes over the narrative, while Ruttie and Jinnah’s fraught relationship takes a backseat. One would be surprised to know Mrs Jinnah had cordial relations with Gandhi, in sharp contrast to Jinnah who considered him nothing short of a charlatan.

In these troubled times, there are some surprising glimpses of love in full bloom. Much to his reluctance, Jinnah would make stops at roadside stalls to get spicy chaat at Ruttie’s insistence. On their shopping trips, Ruttie would spend extravagantly on clothes and furniture, which Jinnah would pay for with begrudging silence. However, domesticity was not a forté for either of the two, and they did not name their daughter — Dinah Jinnah — until she was four!

A new set of characters previously having little bearing on Indo-Pak history make their appearance in the book: B.G.Horniman, Editor of the Bombay Chronicle and Jinnah’s closest friend in his early political years; Kanji Dwarkadas (later Ruttie’s close confidante); Sarojini Naidu, the first female governor of an independent India, and her daughters, who would be like family to an ostracised Ruttie; and Motilal Nehru, who would play the doting father figure to Ruttie. The inclusion in the narrative of these close friends of the couple, gives the story a personal dimension lacking in most historical accounts.

In the end, it was Ruttie’s sudden affliction, which was later diagnosed as abdominal cancer, that would snap the already taut threads that held the two together. In her last years, she would travel back and forth to Europe and India not only to seek treatment, but also to rescue purpose and meaning, neither of which she would be granted. Her last words to Jinnah only reveal love, tenderness and Ruttie’s supreme penmanship:

“I have suffered much, sweetheart , because I have loved much. The measure of my agony has been in accord to the measure of my love.

Darling I love you — I love you — and had I loved you just a little less I might have remained with you — only after one has created a very beautiful blossom, one does not drag it through the mire. The higher you set your ideal the lower it falls.

I have loved you my darling as it is given to few men to be loved. I only beseech you that the tragedy which commenced in love should also end with it.

Darling, Goodnight and Goodbye.

Ruttie.”

As she was interred in the ground according to Muslim burial rites, Jinnah, in a complete breach of character, broke down and wept openly.Through all their misgivings, she truly was the love of his life.

Sheela Reddy does not fall into the temptation of filling in the gaps with her imagination. All the details provided in the book are from archival records and excerpts from official correspondences of the key figures in the story. Her painstaking research has led to a highly readable book uncovering the little known or forgotten facts of important personalities in South Asian history. At its core, Mr and Mrs Jinnah is a story of two remarkable individuals falling in love and later falling apart. The timeless themes of love, loss, grief and finally coming to grips with death, are universal. That is why the book will make for a gripping read for the amateur historian and layreader alike.

The writer has been associated with media and the social sector.He tweets @hadesinshades