Book Review: Love in Chakiwara

By Nusrat Khawaja | Bookmark | Published 7 years ago

Chakiwara of Lyari, despite the energy of its polysyllabic name, does not figure highly on the recreational radar of Karachiites. It is the bastion of a few settler communities such as the Chippas, from which the humanitarian Ramzan Chippa, of the eponymous ambulance service, hails.

Chakiwara of Lyari, despite the energy of its polysyllabic name, does not figure highly on the recreational radar of Karachiites. It is the bastion of a few settler communities such as the Chippas, from which the humanitarian Ramzan Chippa, of the eponymous ambulance service, hails.

Chakiwara, though, has provided rich fodder for the late Urdu writer, Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s (1920-2002), imagination. Akhtar was a trained engineer. His career brought him to Karachi and the city became his permanent home. His short stories and travelogues, marked by sharp observation, established his reputation as a writer. His book Chakiwara mein Wisaal [Tryst in Chakiwara] was published in 1964 in Pakistan.

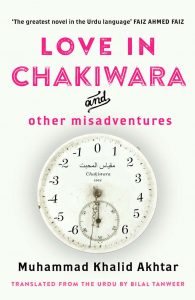

Picador India published an English translation of his work in a handsome hardback last year titled Love in Chakiwara and Other Misadventures. It has been translated by Bilal Tanweer (the author of The Scatter Here is too Great), in fulfillment of the PEN Translation Fund Grant. Tanweer has delivered a brilliant translation that allows non-Urdu readers to enjoy the delights of this Urdu gem by entering into the microcosm of a quirky fictitious universe called Chakiwara.

The author’s preface states his two diverse inspirations for Chakiwara mein Wisaal, which are the town of Chakiwara, where he spent a couple of ‘bohemian’ years, and the writings of Robert Louis Stevenson. Akhtar’s attachment to Chakiwara is acknowledged even on his tombstone which bears the epigraph, ‘Dervish of Chakiwara.’ Despite these links to an actual inner city locality, the Chakiwara of Akhtar’s fiction represents a generic locale where the petit bourgeois are embroiled in the frustrations of daily life.

The book is an assemblage of loosely interconnected tales that are compiled in the form of two novellas. It features an eclectic bunch of characters, some of which have also featured in other anthologies of Akhtar’s short stories.

Our gateway into this microcosmic universe is through the diary notes, “a chronicle of sorts” of the primary character within the book, namely Mr. Iqbal Changezi, the proprietor of Allah Tawakkul Bakery. Iqbal Changezi has a self-effacing temperament and a generous nature. He can never refuse a small loan of money or clothing (never to be returned) to financially challenged friends such as Qurban Ali Kattar, who is a mild-mannered writer of sensational novels with titles like The Comforting Beauty.

The quasi-reality of Chakiwara’s world is created by a variety of mini-portraits of individuals. There’s the highly inventive Dr. Ghareeb Muhammad, whose inventions include the love metre. Maulvi Abdul Samad alias Professor Shahsawar Khan claims to have access to jinns and introduces Faghfur the Jinn to the credulous denizens of Chakiwara. Then, there is the dubious Chakori, with his uncertain relationship to the Chinese dentist, Dr. Ah Fung.

The author introduces a few women in the stories but the narrative remains predominantly about men from a male-centric perspective.

By and large, Akhtar treats his characters with affection, free from moral judgement or sanctimony. His wry view of imperfect humanity is reflected in the peccadillos committed by the residents of Chakiwara. They are representative of certain universal types and are shown in twinned relationships to one another, such as the chronic lender to the perpetual borrower, the shyster to the gullible, and the healer to the sick. They are repetitive in their behaviour patterns and the pleasure of reading about them lies in predictability. Akhtar says: “It’s quite possible that they may not seem like real, full-blooded creatures to anyone, but I daresay there is a certain Wodehousian vitality to them.”

However, in contrast to Wodehouse’s focus on the foibles of the upper class elite, Akhtar’s focus is on the non-elite — on what postcolonial theory terms the ‘subaltern’ — even though Akhtar does not focus on class issues at all. Rather, he treats Chakiwara as a staging ground for exposing the aspirations of the seemingly ordinary people, who can simultaneously be dreamers and pragmatists.

Akhtar is essentially an ironist but his irony is diluted by humour, much like homeopathic medicine with its multiple dilutes. His voice is often detected in the slipstream of Iqbal Changezi’s diary notes, characterised by his signature irony in statements such as: “Chakiwara is a truly autonomous state where anyone can pass themselves off as anything.”

This tongue-in-cheek observation may hold true for the characters. But when Akhtar lets slip in descriptions of Chakiwara as a place, there is no mediation of unpleasant reality. The decay from urban neglect shows strongly in passages such as this: “A little further on from this intersection there is a little ‘garden’: a patch of dried grass with a few miserable and shrivelled mulberry trees inside a rectangular iron railing. This is the Hyde Park of Chakiwara.”

Love in Chakiwara and other misadventures, straddling the duality of the real world and the world of the author’s imagination, is a lovely contribution to the world of Urdu literature, not least because of its profoundly humanist ethos.