Blending Identities

By Gina . Hassan | Art Line | Published 11 years ago

Faiza Butt is one of the front-runners of the new breed of contemporary artists, who have garnered acclaim with the rising interest around the world in Pakistani art. Her ambitious works pay homage to miniature art and the employment of the par dokht-inspired technique is a testament to her inimitable skill. Faiza was trained at Slade and lives in Britain, but her roots are in Pakistan and politics, gender issues, erroneous perceptions and duality of identity are some of her favourite themes.

It had rained all night and it was under a thunderous grey sky that I made my way to Faiza Butt’s home in Stoke Newington, East London. The multicultural neighbourhood is the perfect habitat for an artist, if there ever existed one, which is probably why more artists live in Hackney than in the whole of Paris.

Faiza opens the cerulean blue front door and informs me that her husband Richard has taken their two kids out for the day so that she can do the interview without any distraction. “The merits of marrying an Englishman,” I say to her, and without missing a beat she says, “All men are intrinsically the same no matter where they come from!” Faiza, as I come to realise during the course of our conversation, is not one to leave anything unsaid. Fiercely feministic, she is never shy of being brutally honest.

She is petite and speaks in hushed tones, her words resonating at the edges alternately with very English and, at times, distinctly Pakistani inflections. Beyond the fashionable attire, dip dyed ends of hair and deft strokes of maquillage (“I like my glamour,” she tells me) there lies an intense individual, right beside, the talented artist that she undeniably is. A woman deeply rooted in her heritage, her politics and passion define her art.

Preparations for her solo show called Aalmi at the Vadehra Art Gallery, to be held in India, are underway. Semi-finished works, reminiscent of precious blue Chinese porcelain, in which ancient Chinese dragons are locked in combat with the artist’s children, lie scattered in the room. She has been working at home, as her studio is being renovated. Surrounded by artistic disarray, Faiza and I chat through the afternoon, as the rain pours silently and relentlessly outside the bay windows.

Daughter of a college professor and hailing from a Kashmiri background, Faiza’s extended family was divided between those who had chosen to cross over and those who had not. “My parents were born in Amritsar before they came to Lahore and had lovely memories of a multicultural society, with Sikhs, Hindus, Parsis and Christians living around them. On the contrary I did not grow up in a multicultural environment — only recently did I discover that there are Hindus living in Sindh, which just goes to show how isolated the north can be from the south. While growing up in the ’80s, being a Pakistani was never emphasised upon as something important. We were a Kashmiri family and instead of being Pakistani, being Kashmiri was our sense of identity.”

The strongest moment for Faiza as a budding artist came during the cold war era when, under General Zia’s rule, the culture of Pakistan was forced to shift completely to the right with television, theatre and the arts being censored and stifled. “I had seen my parents dress liberally in the ’70s the parties, the music et al — and then I witnessed the Islamisation of the `80s. In my church school in Lahore, a recitation from the Quran in the morning was declared mandatory. We had to start wearing shalwars — we became gender-conscious, we were told to cover our heads. The school pool was shut down, it was considered un-Islamic.”

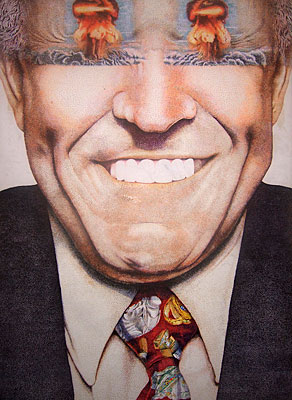

Cinema was used as a very potent source of propaganda during that period, which led to the deterioration and corruption of Pakistani cinema, epitomised by the movie Maula Jatt, which highlighted the celebration of violence by the protagonist. The gigantic cinema posters she saw around Lahore’s Laxmi Chowk were the initial source of influence for Faiza’s graphic and colourful work. “The posters displaying Sultan Rahi covered in blood were fascinating, how on one surface they created titillation, violence, and drama — how they packed everything in. And I still look at popular culture; you cannot underestimate the power of imagery in popular culture.”

Billboards, advertising, graffiti, truck paintings, artisans making terracotta art and other such raw sources, provided inspiration in those early days. “Living in this very gallery-rich city of London, I find art in museums a very refined product. It offers me nothing except that I should admire it. I do a bit of it but I still take my inspiration from going to the flea market, discovering life in the city; my grain still craves those raw sources.”

“To be an artist was always marked out for me. I was the geeky kid who could draw well and would have a flock around me to watch.” Her ability to record information was evident from those initial years at NCA. Salima Hashmi was her personal tutor and a feminist role model, someone she still remains close to. Hashmi stressed on the need for women artists to think of how their role in Pakistani society should translate into their art. During that period Faiza lent many of her works to The Women’s Collective in Lahore. “Initially the narrative of my works was inspired by truck art because although we had just got rid of Zia and the excessive propaganda language to support the ‘mujahideen’ and ‘jihad,’ the idea of ‘shahadat,’ celebrating the militant aspect of religion was still very much there. It was reflected in the religious iconography like the ‘buraq’ on trucks — I absorbed all that folk urban part of it.”

And when Faiza travelled to London for her graduate studies she found herself in a very different world that both fostered and challenged her as an artist.

“During those two years at Slade, the powerhouse of art education, I just wanted to learn and was like a sponge.” Slade was a very English institution when Faiza was there 15 years ago. The faculty had been there since the `60s and their world-view was rather limited as compared to her’s, since she came from vibrant Pakistan and had also spent time in Africa. Also, at Slade came the realisation that justifying herself as a Pakistani was becoming an issue for her. 9/11 and the ensuing Islamic witch-hunt, that labelled every Muslim a terrorist, made matters worse.

Although her initial work featured women and stylised images inspired by truck art, it was while studying European paintings at Slade that she was struck by the depiction of women in the pre-photography period, the sole objective of which seemed to be the titillation of the male audience. Her work from then on was mainly a reaction to this.

Born into a family of five sisters, feminist themes are very close to her. “My mother had those five daughters so that she could have the son she always wanted. It was an obsession that turned into a goal for her, this thing she couldn’t snap out of. She used to do these Quran recitations and she would involve us in the dua. We would be sitting next to her praying for a brother that we had very little emotional connection with. We didn’t really care if we had one or not!”

Perhaps as a result of her feminist and political views, the figures in Faiza‘s works frequently challenge viewers’ perceptions and she is repeatedly asked about the identity of the men in her paintings. These men are of Muslim origin, clearly displaying their faith. She says she never took any notice of them while living in Pakistan but when she came to live in the West and saw what they represented in the western press, she felt compelled to question what their facial hair stood for. Faiza reveals, “I started to develop sympathy for the way the Muslim man is presented. Facial hair is as much a sign of religion as a skullcap or a cross but it started to represent radicalism, so I started using those men initially in a tongue-in-cheek way to set up a trap, to bring out what was in the minds of western audiences. Propaganda fed to them says that two men together are gay; the association is very clichéd and narrow. I created these men with very beautiful faces, as a reaction to the female nude in western history and my paintings have no agenda other than to start a conversation.”

Another aspect of doubles at work is apparent in the picture of two men kissing, which is actually the image of one man kissing his own reflection. Funnily enough that particular piece was very well received in Pakistan but when showed in London, to a western, supposedly liberal audience, it caused people to walk out. They found the homosexuality offensive.

“I talk about homosexuality because it is the Achilles’ heel of human sexuality, a lot of unhappiness stems from it. I do believe that in the three religions, Judaism, Christianity and Islam, human sexuality was branded as bad. If you look beyond that, it’s an important part of Grecian culture and even beyond that it’s not demonised at all. It is a human reality that we crush too much. In Pakistan two of my cousins were in a relationship — criticism was heaped on them and they were quickly married off. Everyone said, ‘Yeh angrezon ki cheez hai.’ I feel that when I approach the human condition through this very sharp angle and if you pass a judgement, it says a lot about you.”

The figures in Faiza‘s works frequently challenge viewers’ perceptions and she is repeatedly asked about the identity of the men in her paintings. These men are of Muslim origin, clearly displaying their faith. She says she never took any notice of them while living in Pakistan but when she came to live in the West and saw what they represented in the western press, she felt compelled to question what their facial hair stood for.

The figures in Faiza‘s works frequently challenge viewers’ perceptions and she is repeatedly asked about the identity of the men in her paintings. These men are of Muslim origin, clearly displaying their faith. She says she never took any notice of them while living in Pakistan but when she came to live in the West and saw what they represented in the western press, she felt compelled to question what their facial hair stood for.

“Everything I do or the way I approach certain issues is always from the perspective of the duality of growing up in Pakistan and the fact that I’m married to a British man and my children are a product of that. My pet theme is how we mark ourselves different. All the wars in the world and conflicts are due to this.” The migratory element is a big part of her psyche; she says that she believes from her experience that you can live in Britain all your life without ever being ‘allowed in.’

“I have to critique this society as such a class-ridden society — they say that if you put five Britons on an island, in five minutes they’ll establish a class system. It’s a kingdom and the cultural references remain the queen and formality; coming from sharp political chaos, my judgements and opinions are far from rosy. They have had such stability for such a long time that it has dumbed down their senses. It has made them inverted. Being an island, Britain is not even a part of Europe!”

Since she was the outsider, married to one of them, she had to be the one who had to integrate. “I learned the hard way, when I went on this adventure of integration; to dress like him, to live like him but soon realised that I was in a costume and I was a prop and not the main lead. It was also how his family always talked about things that isolated us, like sitting at the dinner table they would say things like, you don’t eat pork, knowing that I don’t and other such excluding acts.”

She is disappointed that East London, which is supposed to be very bohemian and left, is still not left enough. “I went out with these girls who live next door; they are liberal and educated and choose to live in East London because they like the multiculturalism. But once I was identified as a Pakistani, I had to defend women in my country. I ended up answering all these clichéd negative questions. I don’t blame them because the poisoning is very consistent — the constant articles on forced marriages in the British press, etc.”

Faiza’s husband and children who came back during the course of our long conversation, are being exceptionally quiet as they move around the house. Dusk starts to cast its shadow on colourful East London, our jasmine tea sits cold and untouched, forgotten during Faiza’s intense recounting of the journey of her life. I leave to return another day to explore intriguing East London at length.