Arts & Culture, Movies

By Samina Ibrahim | Arts & Culture | Movies | Published 20 years ago

When Oliver Stone’s latest production, the 100-million-pound epic, Alexander, is released, look closely at the tents, banners, wall-hangings, the Babylon drapes and the tent interiors. They have been created right here in Karachi at factories and kaarkhanas in Landhi, Korangi, Saddar and Defence. For seven months, around 100 craftsmen worked two shifts every day to complete this mega-project in time. And supervising this mammoth effort was our very own doyenne of the fashion fraternity, Maheen Khan.

When Oliver Stone’s latest production, the 100-million-pound epic, Alexander, is released, look closely at the tents, banners, wall-hangings, the Babylon drapes and the tent interiors. They have been created right here in Karachi at factories and kaarkhanas in Landhi, Korangi, Saddar and Defence. For seven months, around 100 craftsmen worked two shifts every day to complete this mega-project in time. And supervising this mammoth effort was our very own doyenne of the fashion fraternity, Maheen Khan.

Even though she’s no stranger to costume production — Maheen has worked on at least five major theatre and opera productions in Europe — this was her most challenging and ambitious project to date. “By the end of it, we were all falling ill, we’d forgotton what it was to laugh and swore never to undertake something of this magnitude again”, says Maheen. “But now that it’s over, and we know we can do it, I’m ready to take on another one!”

The sets for Alexander involved elaborately embroidered and embellished panels for Alexander’s tents, his war banners, massive panels for the Babylon set, intricate bed covers, huge punkhas and even life-size embroidered pillars. “The punkha alone was 14 feet long and 6 feet high. We had to embroider it with the Ahura Mazda and the spread eagle wings’ symbol , which were then studded with faux rubies,” says Maheen. “This project was a real learning curve for me and I learnt how to improvise at every step. Almost every piece had to be studded with precious stones, and I must acknowledge the enormous help of Mr Hassan Ali Javeri and his son Tapu Javeri, who sourced all the stones I needed and had them made out of glass and other materials. You just couldn’t tell the difference.”

Despite the 100-million pound budget, the sets had to be manufactured at a fairly low cost, without compromising on the opulence. Maheen’s role as the supervisor in Pakistan involved her identifying design houses,material suppliers, as well as craftsmen who could execute the project. “I had to supply everything down to the last thread and braid and check on each piece almost every day,” says Maheen. “So for seven months I spent most of my time on the road! I also learnt how to improvise to cut expenses to fit the budget and the karigars learnt along with me. I had to do all the graphics to scale, sample the embroidery for each piece and then give it to the workers. There was no room for any mistakes or delay, so it was a huge responsibility.”

The embroidery for the Alexander sets were commissioned in both Pakistan and India and Maheen is proud to say that we did a better job: “I was sent two pieces to redo that workers in India had messed up. In fact, Alexander’s war banner had to be redone virtually overnight and delivered to Casablanca. With no direct flights it was impossible to get it there in time for the shooting. I had to ask Tapu to fly with it to London, where he had to hand it over to somebody waiting at Heathrow, who then flew immediately to Casablanca. That’s how precise and tight filming schedules are. Anyway, it was a good feeling to know that our workmanship is so good.”

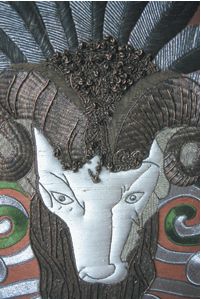

Embroidery for theatre or the movies is radically different to embroidering clothes. In theatre it’s all about impact and definition. Creating a lion’s head in five shades of gold or a ram’s head, where every lock of hair has to be visible from a great distance, is a highly specialised field. “It’s a fascinating world and very different to the one I’m used to. And then, one is invariably working on a very low budget. Theatre or films just use the sets or costumes once, so they want the impact at the lowest possible price. The volume is huge, but their budgets are not.”

Embroidery for theatre or the movies is radically different to embroidering clothes. In theatre it’s all about impact and definition. Creating a lion’s head in five shades of gold or a ram’s head, where every lock of hair has to be visible from a great distance, is a highly specialised field. “It’s a fascinating world and very different to the one I’m used to. And then, one is invariably working on a very low budget. Theatre or films just use the sets or costumes once, so they want the impact at the lowest possible price. The volume is huge, but their budgets are not.”

Now that Maheen has worked in this field for the last 12 years, with major productions like Mozart, Peter Pan, The Aristocrats, Elizabeth, Napoleon, and The Three Musketeers to her credit, she has realised the huge potential and opportunity in Pakistan for producing period theatre, TV or film sets and costumes. “There are so many fashion schools in the country now, but both the faculty and the student body at any institution only focuses on textile or fashion design. They should be taking up embroidery traditions much more seriously. We could take on much more work for the west if we had trained people,” maintains Maheen. “The sheer enormity of the work we did for Alexander, is testimony to what is available to be tapped. For instance, every panel for the Babylon scene was six-and-a half feet wide, and nine-and-a half feet high, and there were 18 such panels, that too double-sided. Each of the 20 curtains in Olympia’s bedroom were 12 feet high and 6 feet wide, ” says Maheen. “And there were countless smaller pieces, including two intricately worked bed-spreads for Alexander and Olympia. I was lucky to find Maheen Hussain, an Indus Valley graduate who worked as my assistant on the project, but she was just thrown into the deep end. She learnt everything on the job, the hard way. The fashion schools and other institutes must introduce embroidery as a course subject.”

Maheen has worked with British set designer, Diana Holmes, for almost 15 years now. “She came over three times to source not just the Alexander sets, but also jewellery, carpets, old Afghan coats and countless yards of silk from the Banaras weavers in Orangi. So many have benefitted economically from Pakistan being used as a source,” says Maheen. “Diana was very fair with the karigars and paid them well. In fact, now they keep ringing me up asking for another project. I believe only 10 per cent of the work was sourced in India, out of which much had to be redone in Pakistan, so most of the sets, as well as the accessories for the crowd scenes have come from Pakistan. I’m happy to say that for this project, it was the workers who made the money. The economy of Landhi and Korangi really sky-rocketed for those seven months.”

Maheen’s job as the consultant also involved stringent quality-control standards. Laws in the west require that the sets are fireproof. And while the fireproofing process is done there, the raw material used here had to be colour fast down to the dabka and the faux stones — which proved to be yet another major nightmare. “If you have a weak heart, this is the wrong line to be in. It’s a sure-fire way to a heart attack,” laughs Maheen. “But the satisfaction of creating something on this scale was amazing, even though we knew we would not get any public recognition. I’m proud to say that Pakistan participated in an international project of this magnitude and executed the order well and on time. Much of the credit goes to the karigars who took on this challenge with unbelievable enthusiasm and commitment and saw it through to the end.”